The “visitation” of the sick poor was one of the three central elements in Catherine McAuley’s vision of the merciful work to which she and, later, her companions in the Sisters of Mercy were called.[1] She conceived of this “visitation” as affording to the desperately ill and dying both material comfort and religious consolation. What is especially striking about her service and advocacy of the sick poor is not only her willingness to care for people with extremely dangerous infectious diseases (cholera and typhus, for example), with the consequent risk to her own life, but her overwhelming desire to offer these neglected and shunned people the dignity and Christian solace that she felt was rightly theirs, as human beings with whom Jesus Christ himself was intimately identified.

In the essay that follows I wish to develop this general theme by focusing on four sub-topics: Catherine’s own ground-breaking and courageous service of the sick and dying poor of her day; the continuation of her vision and practice in her earliest companions; the character of the Christian visitation of the sick which Catherine envisioned and described, especially in chapter 3 of her Rule; and, finally, the implications of Catherine’s practice for care of the sick today.

But, first, what do we know about the state of medical knowledge in the early nineteenth century, when Catherine McAuley took to the streets of Dublin to care for the sick and dying poor? Recalling a few historical facts may help us to appreciate what she faced.

In 1837 William Gerhard, a physician in Philadelphia, published an article in which he demonstrated, for the first time in medical history, that typhoid fever and typhus were two distinct diseases, with different symptoms and causes, despite the prevailing tendency to classify them both as simply “fever.” In 1839 William Budd, a British country physician, began his landmark study of the origin and transmission of typhoid fever, and in 1856 concluded, for the first time in medical history, that typhoid fever is spread by infected human fecal matter, though he could not then identify its specific organic cause. In 1854 John Snow, another British physician, demonstrated during an outbreak in London that cholera is a water-borne disease, spread in a population through contaminated drinking water, but he was unable at that time to pinpoint the responsible agent.

In 1864 Louis Pasteur, aided by further developments in the microscope invented almost 200 years earlier by Anton van Leeuwenhoek (1632—1723), convinced scientists to accept the existence and general character of germs—living microorganisms which cause infectious diseases. In 1865 Joseph Lister inaugurated antiseptic surgery, using carbolic acid to prevent surgical infection. In 1880 the typhoid fever bacillus (salmonella typhosa) was finally identified by the American pathologist, Daniel Elmer Salmon. In 1882 Robert Koch first identified the bacillus which causes tuberculosis, thus accounting for the so-called “consumption” which had brought death to so many, and in 1883 he identified the microorganism responsible for cholera. In 1909 the mode of transmission of epidemic typhus—by infected body lice—was finally demonstrated by Charles Nicolle.[2]

Thus, by the end of the 19th century, developments in microbiology and epidemiology, made possible in part by advances in optical science, finally enabled medical practitioners to know the particular microorganisms responsible for and the respective modes of transmission of a wide array of infectious diseases that had ravaged human life for centuries: anthrax, cholera, dysentery, diphtheria, smallpox, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, and typhus, to name but a few of the most dreaded, and until then often fatal, infectious diseases. It was not, in fact, until 1935 and the two decades following, when the sulfa drugs, penicillin, and other antibiotic agents were first created, that physicians had, at last, effective means of treating outbreaks of these mass diseases. And it was riot until 1977—1980 that the World Health Organization was at last able to declare smallpox eradicated as a human disease, the discovery of the virus which causes it having been previously achieved with the aid of the electron microscope (first constructed in 1931).

But Catherine McAuley died in 1841, when Louis Pasteur was just nineteen years old. She thus lived and worked in a world that had not yet benefited from the discoveries that would come later in the century: a world still fraught with dangerous but as yet unidentified causes of severe sickness and death; a world in which the poor were especially vulnerable because of the overcrowded and decaying condition of their dwellings, their poor sewage disposal, and their unprotected water supplies.

Cognizance of these historical facts is essential for a full understanding of Catherine McAuley’s intimate care of the sick poor and of the deliberate risks involved in her visitations of the sick in the slums of Dublin. Indeed, on at least one occasion in 1832 Sir Philip Crampton, an eminent Dublin physician, strongly advised Catherine to give up the visitation of the sick. It was not that she was unaware of the dangers involved; on the contrary, Clare Moore, one of her earliest associates, records that she had “a natural dread of contagion” (“Bermondsey Annals,” Sullivan 112). But, as Clare also notes, Catherine “overcame that feeling” for the sake of the comfort and consolation she might bring to those who suffered not only the physical pains of illness and dying, but even more, the spiritual pains of abandonment and hopelessness.

I. Catherine McAuley’s Care of the Sick Poor

Karl Rahner speaks of the apostolic “boldness” (parresia) which impelled the public speech of the first followers of Jesus. He notes their daring in publicly proclaiming the Gospel in a world that was hostile to their mission. Believing that they had indeed been “sent” by Jesus into that very world, and for its sake, they overcame their fears, and their preference for silence, and witnessed in words to the revelation they had received, accepting the danger involved (Theological Investigations 7:260-67). Catherine McAuley manifested comparable apostolic boldness in her speech, but even more so in her actions. Her personal presence among the desperately sick poor and her intimate care of them, under all sorts of dirty, unsavory, and exhausting conditions, was an emphatic proclamation of the merciful solidarity with those in need which she believed was at the heart of the Gospel. Thus her visitation of the sick poor emulated the boldness of the one she followed: Jesus, who touched the sores of lepers (Mark 1:41).

Catherine began to visit the sick poor in their own dwellings while she lived with the Callaghans at Coolock House (1803—1822), where she served as a companion to Mrs. Callaghan, but she was obviously able to devote more time to this work after Catherine Callaghan and her husband William had died. However, her first recorded nursing experiences involved, not the sick poor, but the illnesses and deaths of her own relatives and close friends. Her mother Elinor McAuley died in 1798, when Catherine was about twenty: Catherine Callaghan died in 1819, after a “fingering and tedious” illness which kept her bedridden for three years (“Limerick Manuscript,” Sullivan 145); Catherine’s cousin, Ann Conway Byrn, died in August 1822, leaving four children, two of whom Catherine adopted; William Callaghan died in November of the same year, Catherine’s close priest friend, Joseph Nugent, died of typhus in May 1825; her sister Mary died of cancer in August 1827; Edward Armstrong, her confessor, died in May 1828; and in January 1829 her brother-in-law William Macauley died of “ulcerated sore throat attended with fever,” leaving five children all of whom Catherine adopted (“Limerick Manuscript,” Sullivan 161). During all these last illnesses Catherine nursed day and night, sometimes for months, sometimes for only a few days or weeks. It was undoubtedly these experiences of nursing her relatives and friends that taught her how to care for the sick and dying, and that years later, after she had experienced many more deaths of those she loved, led her to write: “the tomb seems never closed in my regard” (Neumann, ed. 100).

Upon the death of William Callaghan in 1822, Catherine inherited most of the Callaghan estate. She continued to live in the village of Coolock just north of Dublin while she planned her future work and built the large house she had designed for this purpose on Baggot Street, Dublin. The Bermondsey Annals says that both before and during this period, “It was her custom to visit the sick poor assiduously, as well in the wretched streets and lanes of St. Mary’s Parish [Liffey Street], Dublin, as in the village near her residence” (Sullivan 101). During one of these visits Catherine met Mrs. Harper.

The Limerick Manuscript records her response:

On one occasion she discovered a poor maniac who had once enjoyed the comforts of life, being of a good family, but was then deserted by all and suffering from extreme poverty. She immediately took charge of this poor creature, and instead of getting her into an asylum, brought her to her own house where she kept her till her death. Miss McAuley had much to suffer from this woman, as she, with the perversity sometimes attending madness, conceived an absolute hatred of her benefactress, and ordinarily used most virulent and contemptuous language towards her. Besides she was of very dirty habits, and had an inveterate custom of stealing everything she could lay hands on, hiding such things as she could not use, which caused great inconvenience in the family. Yet the patience of her protectress never seemed disturbed by these continual annoyances, nor would she permit the servants to teaze [sic] the poor creature on the subject. (“Limerick Manuscript,” Sullivan 151-52)

Although its rooms were not yet fully completed, the House of Mercy on Baggot Stret was opened on September 24, 1827, and Catherine’s first two associates—her adopted cousin, Catherine Byrn, and Anna Maria Doyle—moved in that day to begin the works of mercy Catherine had planned. By June 1828 Catherine herself resided fairly regularly at Baggot Street, when she was not caring for her deceased sister’s young children at her brother-in-law’s home. Coolock House was sold the following September, and in November of that year Catherine asked Archbishop Daniel Murray for permission to visit the sick poor, not only in their own homes, but also in the hospitals of Dublin. Thus began, in late November 1828, three years before the founding of the Sisters of Mercy, the daily visitation of the sick poor which was to characterize the life of nearly all Sisters of Mercy until well into the twentieth century.

The early nineteenth century — both before and after the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 — was not the best of ecumenical times in Dublin, and a mutual fear of proselytism, on the part of both Catholics and Protestants, had led to the exclusion of ministers of all religious denominations from visiting patients in hospitals. Moreover, except for Saint Vincent Hospital opened by the Irish Sisters of Charity in 1834 (Scanlan 8), all of the hospitals in Dublin in Catherine’s day were under Protestant management.[3] This fact explains Catherine’s care—some would say, cleverness—in gaining entry to the poor wards of the hospitals on the south side of Dublin. (According to Mary Vincent Harnett, she left the hospitals on the north side of the city to the ministry of the Irish Sisters of Charity who resided there [Life 57].) The Limerick Manuscript is particularly detailed about Catherine’s method:

It was not permitted at this time for the members of any religious body in Dublin to visit the public hospitals. Miss McAuley wished to remedy this evil, and knowing that the greater number of the patients received into these hospitals were Roman Catholics, she resolved to make an effort to gain access to them for the purpose of communicating instruction and consolation. As she knew that persons would more willingly accede to the request of those who occupied a good position in society, rather than to that made by individuals of humble rank, she resolved for the furtherance of the object she had in view to make her first visits in her own carriage. This she did, not from any motive of ostentation or display, but from a wish to remove the obstacles the world might raise to the fulfillment of her charitable designs; she wished to vanquish the world’s prejudices with its own weapons, and having happily succeeded, she disposed of her carriage in the course of a few months and never resumed it again. Her first visit in this way was to Sr. Patrick Dunne’s [sic] hospital where one of her Protestant friends was head physician. She was accompanied by three of her associates,[4] and while one or two of the governors brought her through the establishment, and showed her several objects of curiosity as the means which modern science has employed for the mitigation of human pain, her young friends were dispersed through the wards ministering comfort to the patients. In the course of conversation she took an opportunity of asking whether there would be any objection on the part of the managers to her visiting from time to time, for the purpose of imparting religious consolation to the poor suffering inmates; the reply was that not the smallest objection should be thrown in her way, and that she was perfectly welcome to visit the patients as often as she wished to do so. She paid a similar visit to Mercer’s Hospital and met with the same success. (“Limerick Manuscript,” Sullivan 159-60)

Besides Sir Patrick Dun’s Hospital and Mercer’s Hospital, Catherine and her associates also visited the sick poor in the Coombe Lying-In Hospital and the Hospital for Incurables in Donnybrook. They walked considerable distances to these hospitals, as well as to the hovels of the sick poor, and thus in time were dubbed “the walking nuns.”

In her book, The Irish Nurse, Pauline Scanlan provides some historical data about the hospitals of Catherine’s day. For example, she notes that Mercer’s Hospital, located in a stone house originally used as a home for poor girls, was founded in 1734 “for the reception and accommodation of such poor sick and diseased persons who might happen to labour under diseases of a tedious and hazardous cure, such as falling sickness [epilepsy], lunacy, leprosy and the like” (2). The operating theatre of Sir Patrick Dun’s Hospital, which was opened on Lower Grand Canal Street in 1809, was still, in Catherine’s day, a single mom, “heated by a stove” and having “neither hot nor cold water laid on.” The new operating theatre built in 1898 was “said to have been the first modem antiseptic theatre” in Ireland (Scanlan 19). The Coombe Lying-In Hospital, “founded in 1826 for poor expectant mothers living in the Coombe area of Dublin,” south of the River Liffey, had thirty-one beds (Scanlan 7). The Hospital for Incurables founded, with one nurse, on Fleet Street in 1744 was moved later in the eighteenth century to Donnybrook Road where it then housed about one hundred patients (ScanIan 2).

As Scanlan notes, “During the eighteenth and for the first half of the nineteenth century, the majority of nurses were classified as domestics, and nursing was considered a function for menials” (55). In a report on conditions in the hospitals in Ireland, published in 1835, the physician-author refers to “problems caused by the ignorance and lack of training of nursetenders and midwives,” for whom cleanliness, proper patient. diets, and ventilation were often not priorities (ScanIan 64). Other commentators have noted that intoxication while on duty was frequent in the nursing staffs of some hospitals in Ireland and England during the first half of the nineteenth century. The nurse-patient ratios were generally high; the water supplies, low; the wards, overcrowded; the laundry services, cumbersome; and the nurses’ duties, wide-ranging. Under these circumstances it is not surprising that untrained and illiterate nurses were exhausted and neglectful, and that non-paying patients, the sick poor, were the least served. According to Scanlan, a report on the Dublin House of Industry written in 1807 states that “forty-eight lunatics, as well as other patients, were being accommodated two to a bed, at the time” (56). It was to such an asylum that Catherine McAuley would not, some years later, consign Mrs. Harper.

The state of nursing care in the Dublin hospitals in the early nineteenth century may be further inferred from the story of Mary Ann Redmond, a wealthy young woman from the south of Ireland who had “white swelling on her knee.” Michael Blake, vicar general of the diocese of Dublin, was a very close friend of Catherine McAuley. He also knew Mary Ann Redmond and in July 1830 asked Catherine to visit her in her lodgings in Dublin. When Mary Ann’s physicians decided to amputate her leg, Michael Blake begged Catherine to allow the surgery to take place at Baggot Street, rather than in hospital. In a letter written fourteen years later, Clare Moore, who was present at Baggot Street at the time, says that “Revd. Mother’s charity readily consented. She was accommodated with the large room which is now divided into Noviceship and Infirmary. Mother Mary Ann [Doyle] and Mother Angela [Dunne] were present while the operation went on, tho’ her screams were frightful. We attended her night and day for more than a month, at the end of which time she was removed a little way into the country where she suffered for two or three months and died in great agony” (Sullivan 89-90). The Bermondsey Annals notes that “During the month that this young person was in the Convent, [Catherine] watched over her night and day with the solicitude of a parent” (Sullivan 104).[5]

But two years later Catherine’s solicitude for the sick met an even more severe test. Three months after the founding of the Sisters of Mercy on December 12, 1831, a violent epidemic of Asiatic cholera struck England and Ireland, reaching Dublin in late March 1832. Meanwhile at Baggot Street, Anne O’Grady had just died of consumption the month before, and Mary Elizabeth Harley, one of the two young women who had gone to George’s Hill with Catherine, was now also dying of consumption, her death hastened by the dampness of the basement kitchen where she had been assigned to work at George’s Hill. Several others at Baggot Street were also sick, three with virulent scurvy, and thus the very future of the Sisters of Mercy was threatened by illness and death (“Dublin Manuscript,” Sullivan 206). In the midst of this severe communal suffering came a public call for help.

In late April, as the number of cholera cases and fatalities grew, and contamination spread in the existing hospital facilities, the Dublin Board of Health decided to open some temporary cholera hospitals: in the western part of the city, Grangegorman Penitentiary was converted into a hospital, and placed under the care of the Irish Sisters of Charity; to the east, the Townsend Street Depot was convened, and the Sisters of Mercy were asked to take charge of nursing there. Thus a few days after Elizabeth Harley’s death on April 25, Archbishop Murray came to Baggot Street, at Catherine’s request, to give the community permission to undertake this dangerous work. He had himself, the day before, published a pastoral letter on the epidemic (Meagher 154-56). Though the Grangegorman hospital was closed after three months, the Townsend Street hospital remained open for the rest of the year, and the Sisters of Mercy nursed cholera victims there for over seven months, from early May until December 1832. At the height of the epidemic over 600 people died in Dublin each day. The Townsend Street hospital, initially intended to accommodate fifty patients, was soon expanded, though, in the course of a day, the same bed was often occupied by several patients in succession. Mary Austin Carroll claims that 3,700 cases of cholera were treated in the Townsend Street hospital (Leaves 2:295).

All the early biographical manuscripts about Catherine McAuley reflect on this extraordinary experience. In her “Memoir of the Foundress” (“Dublin Manuscript”), Clare Augustine Moore says:

The deaths were so many, so sudden, and so mysterious that the ignorant poor fancied the doctors poisoned the patients, and as immediate burial was necessary it was reported that many were buried alive. Some no doubt were, but there is reason to believe very few indeed. It was under these circumstances that Revd. Mother offered her services to the cholera hospital, Townsend Street, which were thankfully accepted. The Archbishop having approved of this step the sisters entered on their duties to the great comfort of the patients and doctors; but the fatigue they underwent was terrible. Revd. Mother described to some of us the sisters returning at past 9 [p.m.], loosening their cinctures on the stairs and stopping, overcome with sleep. (Sullivan 207)

In her letter of August 26, 1845, Clare Moore says that Catherine was at the hospital “very much….and once a poor woman being lately or at the time confined, and died just after of Cholera, dear Revd. Mother had such compassion on the infant that she brought it home under her shawl and put it to sleep in a little bed in her own cell, but as you may guess the little thing cried all night, Revd. Mother could get no rest so the next day it was given to some one to take care of” (Sullivan 97-8).

According to Mary Ann Doyle and Clare Moore,[6] the sisters went to Townsend Street in four-hour shifts, starting at eight or nine o’clock in the morning. Four sisters served at a time—even though there were then only eleven in the Baggot Street community, and the school for poor girls and the shelter for homeless women were now in full operation. Catherine herself remained at the hospital all day, supervising the care of the patients and the work of the hired nurses. Clare Moore claims that Catherine “scarcely left the hospital. There she might be seen among the dead and dying, praying by the bedside of the agonised Christian…and elevating his hem to God by charity” (“Bermondsey Annals,” Sullivan 112). Because the cholera deaths were so numerous and rapid, fear spread among the poor that patients were being buried alive. Consequently, Catherine herself assumed personal responsibility for the dead and dying. As Mary Austin Carroll notes:

She would allow no one to be buried till she had assured herself by personal inspection that life was really extinct, nor would she allow the nurses to cover the faces of those supposed to be dead, till a stated time elapsed. These were necessary precautions, which probably saved thousands from a fate more dreadful than even death by cholera…. She was very severe with nurses who neglected the sick, or seemed in too great a hurry to get rid of the dead; nor did she spare some physicians, who, undismayed by the horrors of the dreadful crisis, thought only of the honor of discovering a specific [a remedy] against the pestilence, and who, in their ardor for experimenting, seemed to forget that their patients were human beings. (Life 226)

Besides the fear of burial alive, the poor—especially those who had had no previous experience of the violence of cholera or the discoloration of its victims—feared letting the cholera cans take their stricken relatives to the hospitals because they believed the doctors were poisoning the patients. Even Archbishop Murray’s pastoral letter could not fully persuade them that this was not the case. At the Townsend Street hospital apparently only the constant presence of Catherine McAuley, the Sisters of Mercy, and some Catholic clergy—including Catherine’s friends, Michael Blake and Thomas O’Carroll—could adequately reassure the patients and their families. According to Mary Vincent Harnett, the people “became more reconciled when they saw the sisters accepting and administering the prescriptions from the doctors” (Life 88).

Cholera is a violent diarrheal disease “characterized by devastating intestinal loss of fluid and electrolytes, the replacement of which constitutes the vital element in treatment” Without this, “death may result from dehydration or salt imbalance” (Oxford Companion to Medicine 1:213,596). In Catherine’s day patients were treated by bloodletting, applications of heat, doses of calomel, and such palliatives as opium, laudanum, and brandy. The sisters moved from bed to bed all day long, administering these remedies and wiping the icy cold perspiration from the patients’ bodies. It is no wonder then that Mary Ann Doyle, having repeatedly crawled from low bed to low bed, injured her knees in the process. Catherine’s famous doggerel poem, “Cholera and Cholerene,” was written at this time, as a humorous tribute to Mary Ann’s two sore joints.

A year later, Dr. Andrew Furlong, a physician who had worked side by side with Catherine for seven months in the Townsend Street hospital, stated that Dr. Hart, the head physician in the hospital, said of the Sisters of Mercy, “‘They were of the greatest use, and…the hospital could not be carried on without them. They kept the eighty nurses in order, which was hard to do.’” Dr. Hart apparently gave Catherine “the fullest control” and, according to Mary Austin Carroll, “used to attribute the fewness of the deaths (about thirty percent), in comparison with [the] high percentage elsewhere, to her wise administration” (Leaves 2:295).

In the nine years which remained of Catherine’s life, she continued to make the care of the sick and dying poor a very high priority, even when visiting them took a heavy toll on her own health. When she founded the branch house in Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire) in 1835, the Bermondsey Annals notes that though she immediately started a school for the poor, neglected girls she saw there (Neumann, ed. 86-87), “they also visited the sick, going often to a very great distance, and our good Foundress, notwithstanding the difficulty she experienced in walking, never spared herself in those labours of charity and mercy” (Sullivan 114).

In the first decade of the Sisters of Mercy, twenty of the congregation died—of typhoid fever, typhus, consumption, and erysipelas (a severe streptococcal infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues). Catherine herself died on November 11, 1841, of pulmonary tuberculosis complicated by empyema. Since it is well-known that she frequently suffered bouts of sore gums, so severe that she could barely eat an infant’s diet (Neumann, ed. 195), it is also possible that she had scurvy, a condition resulting from a deficiency of vitamin C. It is doubtful that many fresh fruits and vegetables were available at Baggot Street.

II. The Continuation of Catherine’s Vision and Practice

In the years after Catherine’s death, her companions and followers in the Sisters of Mercy continued her unstinting care of the sick and dying poor and repeatedly entered into dangerous ministries among the sick poor that would have both worried and pleased her. It is not possible here to recount all the visitations of the sick that occurred in the nine foundations of the Sisters of Mercy which Catherine established outside of Dublin, but three events may serve to illustrate her companions’ devotion to the desperately ill: the cholera epidemic of 1848—1849, the Crimean War, and the cases of endemic smallpox in London in 1862.

The Irish Famine—often called the Great Starvation or the Great Hunger—began in 1845 with the blight of the potato crop, then the sole food of a third of the Irish people (Ô’ Tuathaigh 203). It lasted for five years, during which about 800,000 to 1,000,000 people are estimated to have died—from starvation, from the diseases which normally accompany famine (typhus, typhoid or relapsing fever, dysentery, dropsy and scurvy), and from a devastating invasion of cholera. Every city and town in Ireland where Sisters of Mercy then lived was assailed in one way or another by this multi-faceted human disaster. With the reticence that often marked references to the Famine on the part of ordinary Irish people, the comments on the Famine in the existing annals of the early Mercy communities are brief. More detailed are their accounts of nursing the victims of the accompanying diseases.

The Limerick Annals, for example, records that in the severe cholera epidemic that struck the whole of Ireland from December 1848 through 1849 the Sisters of Mercy of Limerick, led by Mary Elizabeth Moore, worked at two cholera hospitals. Elizabeth had entered the Baggot Street community in June 1832 and had nursed with Catherine McAuley at the Townsend Street Depot during the 1832 epidemic. She was thus well aware that cholera can be conveyed by the feces of infected victims, even though its origin is contaminated water. Therefore when the outbreak reached Limerick in the spring of 1849, Elizabeth asked the community only for volunteers, to accompany her in serving cholera victims at two hospitals in Limerick: Barrington’s and St. John’s. Their nursing began on March 6, the sisters staying at these hospitals day and night.

Marie-Therese Courtney, drawing on the Limerick Annals, reports that:

The constant active attendance [at these hospitals] continued for over a month, fresh detachments of four relieving the other[s] in each hospital. On their first night in St. John’s nineteen people died. Mother Elizabeth made her daily rounds to all the wards and patients in both hospitals….

On Holy Saturday, April 7 [as the cholera epidemic began to decline], the night watching ceased and all returned to the convent, but for three weeks afterwards they continued daily to attend the sick in the hospitals. (Courtney 38, 39)

In Dublin in 1832 no Sister of Mercy had contracted cholera, but in Limerick in 1849 two sisters became infected. Although one recovered, the other, Mary Philomena Potter, died on April 19 of the disease, “caught in her service of the sick at Barrington’s—and [from] sheer exhaustion” (Courtney 39). Similarly, in Galway, in the same year, where the Sisters of Mercy nursed cholera victims day and night in the Fever Hospital a short distance from the convent, two sisters died of the disease: Mary Joseph Joyce and Mary Agnes Smyth.

Perhaps the most dramatic and well-known of the nursing experiences of the early Sisters of Mercy is their service from late 1854 to mid 1856 in the British military hospitals in Turkey and the Crimea during the Crimean War. Twenty-three Sisters of Mercy volunteered to nurse in these hospitals at the request of the British government: eight from Bermondsey, London, under the leadership of Mary Clare Moore; and a second group of fifteen (twelve from Ireland, two from Liverpool, and one from Chelsea, London), under the leadership of Mary Francis Bridgeman of Kinsale. Mary Angela Bolster’s book, The Sisters of Mercy in the Crimean War, draws on diaries and letters which focus chiefly on the experiences of the Irish contingent, while correspondence and annals in the Bermondsey archives focus primarily on the experiences of the Bermondsey contingent. Both of these sources document this extraordinarily difficult nursing service, undertaken just thirteen years after Catherine McAuley’s death.

The two sisters from Liverpool died in the Crimea: Mary Winifred Sprey, of cholera, on October 20, 1855; and Mary Elizabeth Butler, of typhus, on February 23, 1856. Both contracted their fatal diseases in the wards where they served, and their deaths were the most severe of the physical afflictions the sisters endured in the War. But there were other daily sufferings and hardships that also took a heavy toll: the filthy wards and quarters where they worked and lived; the constant rats and lice; the scanty food, clothing, and water, the long hours of heart-breaking work; the freezing cold, alternating with the humid heat; the bureaucratic delays in the Purveyor’s function; the lack of linen and other medical supplies; the many medical officers who resented the presence of female nurses (the first such nurses in British military history); and, more than all the rest, the constant arrival from the front of severely wounded, emaciated, disease-afflicted soldiers, and the horrendous mortality rates. About 250,000 Allied soldiers (English, Irish, Scottish, French, and Sardinian) died in the Crimea, most of them from infections, diseases, especially cholera, and other non-combat ailments. Only 70,000 suffered battle deaths.[7] In February 1855, during the first winter in the Crimea, the deaths at the Koulali Barracks Hospital in Turkey, where the Irish sisters then served, averaged fifty-two percent; at the Scutari Barracks Hospital, where the Bermondsey sisters served, the mortality rate was forty-two percent (Bolster 134). Later that year some of both groups moved across the Black Sea to hospitals nearer the front. When the surviving twenty-one sisters returned to Ireland and England in the Spring and Summer of 1856, they left behind the graves of the two who had died in the Crimea, but carried home memories and experience that would strengthen all their future visitations of the sick and dying poor and would inform all the future Mercy hospitals where these women would ever serve.

The only striking difference between the two groups of Sisters of Mercy who served in the Crimean War is the character of their relationship with Florence Nightingale, the General Superintendent of the Female Nursing in the British Military Hospitals in Turkey and later in the Crimea. The relationship between Miss Nightingale and Mary Francis Bridgeman and the Irish sisters was generally negative, to the point where Florence Nightingale eventually, but privately, called Francis Bridgeman “Revd. Mother Brickbat,” and for their pan, Francis Bridgeman and the Irish sisters, acting on their understanding of the conditions under which they had come to the Crimea in the first place, resigned their posts at Balaclava Hospital in February 1856 and went home, rather than accept her authority. The relationship between Florence Nightingale and the Bermondsey sisters was, from beginning to end, mutually positive, to the point where she became a lifelong friend of several of them.[8]

But what is most important in the Crimean War experience of all these sisters is the sheer fact that the experience occurred at all: namely, that twenty-three Sisters of Mercy with no previous travel outside of Ireland or England, and with no formal training in nursing, let alone in nursing in a war zone, freely volunteered on extremely short notice (the Bermondsey sisters had two and a half days to decide and pack) to go on a month’s hazardous journey to the Near East to succor desperately sick and dying soldiers, just because they and their advisors had heard, through the reports of the London Times correspondent in Constantinople (in mid October 1854) that there was a shortage not only of surgeons and medical officers, but of wound-dressers and nurses, and that the wounds, diseases, and deaths of hundreds upon hundreds of soldiers were unattended and unrelieved. In speaking of the visitation of the sick, Catherine McAuley had urged the sisters to “prepare quickly” for this crucial work of mercy (Rule 3.4, Sullivan 298). What is most moving about the Crimean War experience of these Sisters of Mercy is not their widely praised service in the military hospitals, but the self-forgetful spontaneity and whole-heartedness with which they immediately went to the war zone when they realized the desperate need.

The final event that may illustrate the bold fidelity of the first Sisters of Mercy to the sick and dying poor is a much simpler one: Mary Clare Moore’s visit to two poor, smallpox-stricken families in London, on her way home from other work. This event is recorded in Clare’s letter to Florence Nightingale, written on October 13, 1862, when Clare was forty-eight years old. In the letter Clare, who frequently suffered from pleurisy aggravated by her experiences in the Crimean War, apologizes to Florence for not writing sooner to thank her for the fruits and vegetables Florence regularly sent to the Bermondsey convent: “our good Bishop [Thomas Grant of Southwark] sent so many papers to be copied that I could not get a moment.” But then she adds:

I went to St. George’s Church this morning to bring home my writing to the Bishop as I wanted his advice about some of our Convent business— on my way back I felt I must go out of my way to see a poor family. The children have been obliged to stay from School on account of small pox—five, had it—one died—a dear little child of six. Her younger sister greeted me by pulling out from a dreadful piece of rag a halfpenny for the poor— “for Katie’s soul!” I could not well describe their own wretchedness for the father has been in a dying state for months. We had five shillings to give them—a small fortune—but I could not help• feeling it was the dear child’s selfdenial & faith which drew me there, for I hesitated to add to my walk—already very long for me.

We then went on to a poor young man in the last stage of consumption, his only child of two years old lying at the foot of his bed in small pox of the worst kind, his poor wife making sacks, or rather unable to make them on account of the child’s illness. Poor man, he was very ignorant & inattentive to Religion—now full of joy haying received all the Sacraments. It is a great pleasure though a sad one to be devoted to the Service of the Poor.ix

These two sad scenes, in which the wretched illnesses and deaths of the London poor are embraced so naturally and sympathetically, in the course of an ordinary day, were repeated thousands of times in the two decades following Catherine McAuley’s death. In the wicker baskets which the first Sisters of Mercy carried to the sick poor there were no cures, no miraculous restorations of health—only a few shillings, or some bread, or some coals for the hearth. Yet these women sought to bring to the poor much more than small practical helps, and much more than the nursing skills which they had acquired. They wished to bring the only gifts they really had to give: hope and bust in the consolation of a merciful God.

III. Catherine McAuley’s Understanding of Christian Visitation of the Sick

It was Catherine’s deep conviction that the greatest suffering of the poor, especially in their dire sicknesses and deaths, was their lack of religious knowledge, their lack of awareness of God’s tender love and mercy. Of all the poverties induced in Ireland by the long Penal Era, religious ignorance of the merciful fidelity of God was not the least—a longstanding byproduct of proscribed schooling, of forbidden Masses, of at least a century of outlawed priests, and, later, of tiny, over-crowded chapels in back alleys and farm fields. These privations had their long-term negative effects, not so much on the broad outlines of the religious faith of the poor as on their personal belief that they were indeed beloved of God. As they lay on their piles of straw in their wretched hovels it was all too easy to think that God was too distant to notice their plight or to care for their suffering families.

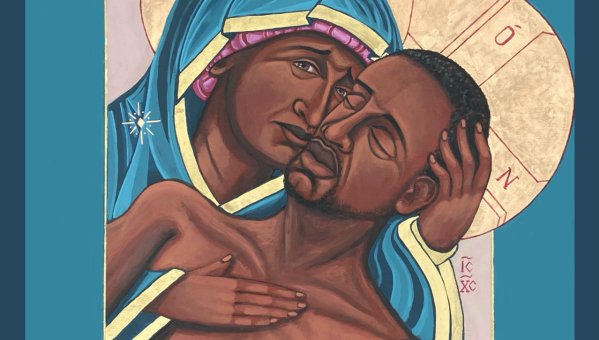

Therefore the primary purpose of the visitation of the sick poor, as Catherine envisioned and described it, was to bring to the poor the comfort and consolation of God: to make known to them—by one’s words, presence, prayer, and tenderness—that God in Christ was indeed present to them and in them, and that, though they suffered grievously, God was indeed at work in them, bringing lasting joy out of their affliction. Catherine’s primary goal as she knelt or sat by the bedside of the sick and dying poor was to encourage, by every human means in her power, their hope and mast in these Christian realities.

It was not that she saw herself as a privileged emissary of God. Rather she saw the suffering poor themselves as the living presence of her afflicted God. Three times in her Rule for the Sisters of Mercy she quotes Matthew 25.40: “Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.” In the first paragraph of the chapter, “Of the Visitation of the Sick,” she writes:

Mercy, the principal path pointed out by Jesus Christ to those who are desirous of following Him, has in all ages of the Church excited the faithful in a particular manner to instruct and comfort the sick and dying poor, as in them they regarded the person of our Divine Master who has said, “Amen, I say to you, as long as you did it to one of these my least brethren, you did it to Me.” (Rule 3.1, emphasis added)

Later in this chapter, she writes:

Let those whom Jesus Christ has graciously permitted to assist Him in the Persons of his suffering Poor have their hearts animated with gratitude and love and placing all their confidence in Him ever keep His unwearied patience and humility present to their minds, endeavouring to imitate Him more perfectly every day in self-denial, [composure] patience and entire resignation. Thus shall they gain a crown of glory and the great title of Children of the Most High which is assuredly promised to the merciful. (Rule 3.3, emphasis added)

And in paragraph six she writes:

Two Sisters shall always go out together. The greatest caution and gravity must be observed passing through the streets, walking neither in slow or hurried pace, keeping close, without leaning, preserving recollection of mind and going forward as if they expected to meet their Divine Redeemer in each poor habitation, since He has said, ‘Where two or three are in my name I will be.” (Rule 3.6)[10]

Besides the discreet way in which Catherine is here introducing beyond-the-cloister activity into the Rule and daily life of women religious—a practice not all that common in the church of her day—the solemnity of paragraph six is chiefly explained by her view of the awesome end of journey: the meeting of her Redeemer “in each poor habitation.” For Catherine, the visitation of the sick was an intense and reverent communion with Jesus Christ who, she believed, “testified on all occasions a tender love for the poor and declared that He would consider as done to Himself whatever should be. done unto them” (Rule 1.2). Hence she believed that the Sisters of Mercy should approach this privileged encounter “preserving recollection of mind” (Rule 3.6).

Even during her early days with the Callaghans at Coolock House, Catherine had the spiritual needs of the poor primarily in mind. The Limerick Manuscript says of her during this period:

Her charity did not confine itself to the relief of their temporal wants only; she took pity on their spiritual ignorance and destitution…. Her solicitude for the interests of the poor soon drew around her many who hoped to derive from her advice, relief, and Consolation. Everyone who had distress to be relieved, or affliction to be mitigated, or troubles to be encountered came to seek consolation at her hands, and she gave it to the utmost of her ability; her zeal made her a kind of missionary in the small district around her. (Sullivan 144)

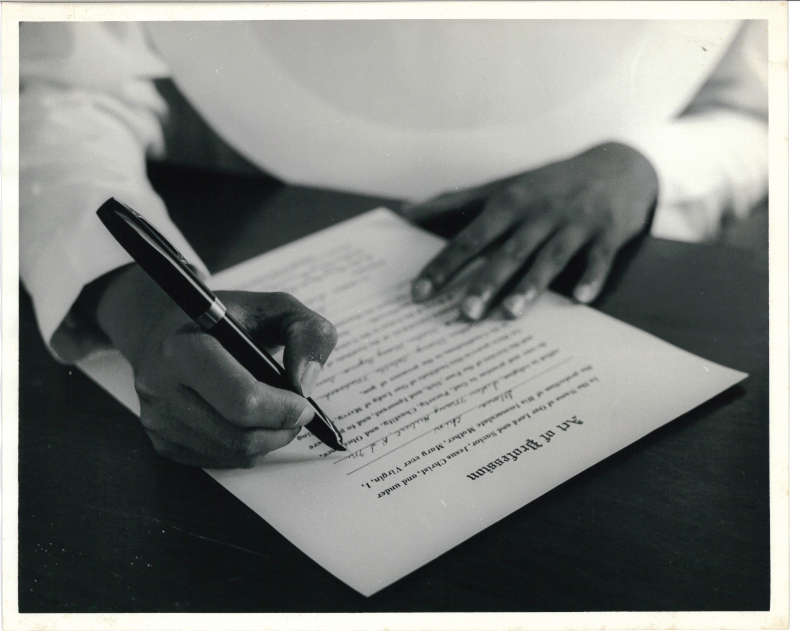

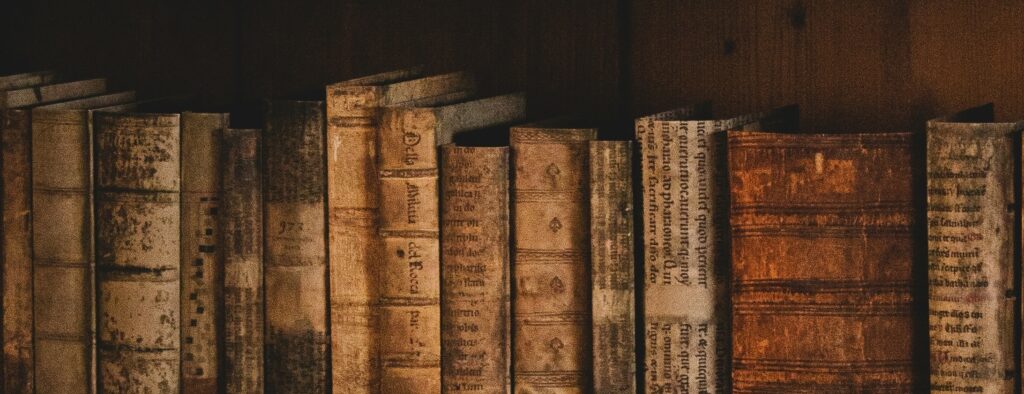

Probably at this time, but certainly after Baggot Street was opened, Catherine began the practice of transcribing prayers that would be consoling to the sick poor. The Limerick Manuscript tells how, after she had moved permanently into Baggot Street in 1829, she would use the early morning hours for transcribing:

The Sisters, as they now called themselves…, rose early and had regular devout exercises of prayer and spiritual reading. Although these were of considerable length they did not suffice for Miss McAuley’s devotion, who besides private meditations used to rise earlier than the rest with one or two of the Sisters to say the whole of her favorite Psalter, and read some spiritual book. One of these Sisters had volunteered to be caller, and it frequently happened that mistaking the hour in the Winter mornings, she used to call at three o’clock instead of half past four, the hour they had proposed to rise at. On these occasions Miss McAuley would fill up the intervening time by selecting and transcribing from pious books certain passages that might be useful for the instruction and consolation of the sick poor. She had made a good collection of them when one day while searching for some document in her desk, near which was a lighted candle, her manuscript happened to catch fire which she did not perceive until it was too late to save it. (Sullivan 161-62)

Although this manuscript was destroyed, similar manuscripts were not. Handwritten copies of Prayers for the Sick and Dying are preserved in the archives of many of the first communities of Sisters of Mercy in Ireland and England. Though none of the extant copies I have seen appears to be in Catherine’s handwriting, the practice of transcribing collections of prayers to read at the bedside of the sick and dying poor certainly began under her leadership. The Bermondsey Annals claims that even when Catherine lived at Coolock, “It was her chief recreation to copy prayers and pious books” (Sullivan 100).

In the Dublin archives of the Sisters of Mercy, there are at least two collections of prayers to be prayed while visiting the sick.[11] One of these, simply labeled “Prayers, Etc.,” may have been intended for use at the bedside of sick and dying sisters; the other, labeled “Visitation of the Sick Devotions,” was clearly intended for use at the bedside of the sick and dying poor. In both collections there are prayers “when recovery is still hoped,” acts of resignation, prayers “when recovery is not expected,” and prayers “for a happy death.” These prayers were probably not composed from scratch, but were transcribed from published prayerbooks. Numerous prayers for the sick appear in the prayerbooks Catherine and the Baggot Street community are known to have used: for example, William A. Gahan’s A Complete Guide to Catholic Piety and Joseph Joy Dean’s Devotions to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Although the collections of prayers in the Dublin archives do not appear to have come from either of these published books, they may have come from comparable prayerbooks available in Catherine’s day. The spirit of all the prayers in the extant collections is one of realistic appraisal of human life and humble confidence in the compassion of a merciful God. For example, the “Prayer, when recovery is still Hoped” is addressed to Jesus Christ, and begins as follows:

To thy infinite goodness, O Jesus, we recommend this thy servant whom thou hast been pleased to visit with this illness, and beseech thee to take her under thy care, be thyself her physician, and bless the remedies which shall be used, that so they may be conducive to the restoration of her health. The compassion thou didst ever manifest towards the sick encourages us to hope that thou wilt strengthen and comfort her under her sufferings. Enable her, we beseech thee, to bear whatever portion of the Cross thou hast appointed for her with a Christian spirit in all humility and patience. Sanctify her sickness and if it be pleasing to thy holy will and beneficial to her eternal interests restore her again to health. Help her, direct her, and support her, O Lord; for as thou art Just so thou art Merciful. And that thou wilt shew mercy to this thy servant we confidently hope through the merits of thy own sufferings and death. Amen Jesus.

The existence of these manuscript prayers illustrates what Catherine had in mind when, in the chapter of the Rule on the “Visitation of the Sick,” she wrote: “One of the Sisters should be capable of reading very distinctly and have sufficient judgment to select what is most suitable to each case. She should speak in an easy, soothing, impressive manner so as not to embarrass or fatigue the poor patient” (Rule 3.7).

Catherine realized that the physical needs of the sick and dying have a natural priority, at least chronologically. She therefore advised that:

Great tenderness must be employed and when death is not immediately expected it will be well to relieve the distress first and to endeavour by every practicable means to promote the cleanliness, ease and comfort of the Patient, since we are ever most disposed to receive advice and instruction from those who evince compassion for us. (Rule 3.8)

But she also believed that “The Sisters [who visit the sick poor] shall always have spiritual good most in the view” (Rule 3.9). In keeping with the theology of her day, paragraph nine of the chapter on the Visitation of the Sick speaks of “the dreadful judgments of God towards impenitent sinners” and claims that “if we do not seek His pardon and mercy in the way He has appointed, we must be miserable for all Eternity” (Rule 3.9). In the rather harsh language of contemporary sacramental theology, Catherine is here simply affirming that the primary goal of the visitation is to help the patient realize his or her only secure joy: a right relationship with God; she therefore urges the sisters who visit the sick to in an audible voice and most earnest emphatic manner, that God may look with pity on His poor creatures and bring them to repentance,” for as she says, “if our hearts are not affected in vain should we hope to affect theirs.” Moreover, the sisters should not hesitate to “question [the patients] on the principal mysteries of our Holy Faith, and if necessary instruct them” (Rule 3.9).

In the next to last paragraph of this chapter of the Rule Catherine deals with the death of the sick poor. She says:

When recovery is hopeless it must be made known with great caution and if time permit done by degrees, assuring them of the peace and joy they will feel when entirely resigned to the will of God, inducing them to pray, that He may take all that concerns them into His Divine care and dispose of them as He pleases. Let the Sisters, if possible, promise attention to whatever object engages their painful, anxious solicitude that the mind may be kept composed to think of God alone. (Rule 3.10)

Among the several alterations made in Catherine’s text of the Rule when it was approved in Rome, the last sentence of this paragraph was omitted and two long, cautious sentences were substituted, to the effect that when the sisters visit the dying they are no longer free, in Catherine’s simple language, to “promise attention to whatever object engages [the patient’s] anxious solicitude,” but, now, even in dire circumstances: “Should the conversation tum on disposal of property by will, let the Sisters dexterously avoid taking part in it…. When again the subject tums on procuring relief for the indigence of the sick person’s family, let them promise, as far as depends on them, to attend to it, in the manner their state permits….” (Sullivan 279). One can hardly imagine a Vincent de Paul, or a Catherine of Genoa, or a Catherine McAuley writing such sentences to cover the dying moments of a poor man or woman lying on straw in a hovel, with his or her family weeping in the shadows.

Catherine was, evidently, deeply guided by the example of the saints. According to Clare Moore’s letter of September 1, 1844, at least from June 1829 on, the community on Baggot Street listened to a reading from the lives of the saints each day: “Breakfast 8 or 8 1/4, and immediately after in the Refectory, Revd. Mother read the saint for the day” (Sullivan 90). It is reasonable to assume that these readings were from Alban Butler’s Lives of the Saints, the widely available compilation first published in 1756-59. Among the many significant changes Catherine made to the Rule of the Presentation Sisters when she revised it for the Sisters of Mercy was the addition of three names to the list of “Saints to whom the sisters of this Religious Institute are recommended to have particular devotion”: Catherine of Genoa, Catherine of Siena, and John of God (16.4). These particular additions demonstrate the critical importance Catherine attached to care of the sick.[12] The other saints whom she mentions in the Rule were equally inspiring to her. In the chapter on the “Visitation of the Sick,” she lists nine saints who “devoted their lives to this work of Mercy”: Vincent de Paul, Camillus de Lellis, Ignatius Loyola, Francis Xavier, Aloysius Gonzaga, and Angela Merici, as well as John of God, Catherine of Siena, and Catherine of Genoa.

IV. Some Implications of Catherine’s Practice for Care of the Sick Today

In his essay on “The Church of the Saints,” Karl Rahner says:

The nature of Christian holiness appears from the life of Christ and of his Saints; and what appears there cannot be translated absolutely into a general theory but must be experienced in the encounter with the historical which takes place from one individual case to the other. The history of Christian holiness (of what, in other words, is the business of every Christian…) is in its totality a unique history and not the eternal return of the same. Hence this history has its always new, unique phases; hence it must always be discovered anew (even though always in the imitation of Christ who remains the inexhaustible model), and this by all Christians. Herein lies the special task which the canonized Saints have to fulfil for the Church. They are the initiators and the creative models of the’ holiness which happens to be right for, and is the task off their particular age. They create a new style; they show experimentally that one can be a Christian even in “this” way; they make such a type of person believable as a Christian type. Their significance begins therefore not merely after they are dead. Their death is rather the seal put on their task of being creative models, a task which they had in the Church during their lifetime, and their living-on means that the example they have given remains in the Church as a permanent form…. For the history of the spiritual means precisely that something becomes real in order to remain, not in order to disappear again. (Theological Investigations 3:91-104)

How shall the “permanent form” of Catherine McAuley’s courageous care of the sick and dying remain vividly alive in the present historical moment, especially among Sisters of Mercy, their associates, and those who admire her? What are the implications of Catherine’s practice for our care of the sick today? I conclude this essay with some brief reflections on this question.

In her “Memoir of the Foundress,” Clare Augustine Moore, whose sister Mary Clare Moore was one of Catherine’s earliest associates, recalls the Spring of 1832 at Baggot Street:

Three were attacked with virulent scurvy, all the others ill. This took place soon after Sr. M. Elizabeth’s death on Easter Monday.[13] Revd. Mother who notwithstanding her love of austerities was always and most kind to the sick did her best to restore them. The Surgeon General, the late Sir P[hilip] Crampton, was called in, I forget to which of them; [and] he, having always less faith in medicine than management, inquired into their food and occupations, and at once declared that an amellioration [sic] of the diet would be the best cure, and especially he ordered beer. He tried to convince her of the real unwholesomeness of the visitation, but she never could understand, and always maintained that fresh air must be good, forgetting that it must be taken by us mostly in Townsend Street and Bull Alley.[14] (Sullivan 206-7)

The question for Catherine McAuley and for those who follow her really comes down to this: To what extent do we plan to avoid virulent scurvy and typhus, or their modem equivalents? If our answer to this question is not a complete and unqualified rejection of all harm and inconvenience to ourselves, then where are the Townsend Streets, the Bull Alleys, the Depots, the hovels, the fever hospitals of our day? Who suffer and die there, and how and why shall we walk to their bedsides as Catherine did? And what attitudes toward our own personal and corporate lives and what accretions to our life-styles will we have to forsake on the way? How far will we wish to distance ourselves from the desperately ill and dying? With what theories will we justify leaving the care of the sick poor to those among us who happen to serve in hospitals? As Sisters of Mercy, in particular, how neatly will we divide our common vow of service to “the poor, the sick, and the ignorant” into three separate lists of ministers? And how will we then exempt ourselves from personal commitment to the whole vow, and settle for just a part of it?

These are very, very hard personal and corporate questions, especially for Sisters of Mercy, but they are, I believe, questions Catherine might ask, especially in view of the poverty, sicknesses, deaths, and epidemics that now unmistakably stare us in the face—in the United States, and in the world at large. They would not be such hard questions if we had not become to some extent domesticated—by the church, by our own mode of functioning, by our jobs and salaries, by our perceived financial needs; and bureaucratized—by our civic governments, by our culture, by our own internal management, and by our working concepts of ministry and vocation. Is it possible that we have lost some of our agility, our freedom, our readiness to respond to desperate needs? Is it possible that we who are committed to relieving misery and addressing its causes (Constitutions 3) have become so focused on systemic change which addresses the causes of suffering that we have become somewhat distracted from relieving miseries one by one? Have we in part lost our belief that it is also worth our time to relieve the misery of just one desperately sick poor person, of just one poor ailing family?

If a cholera epidemic breaks out tomorrow, who will go to the Depot? Yes, modem hospitals will take care of it, but what about the epidemic drug addiction and drug-related violence in our cities? Who will go there on short notice? Who will stay there overnight? Who can? How many Sisters of Mercy in the United States will visit the poor wards of county hospitals this week, or the AIDS wards? If the family of a poor dying woman calls one of our convents tonight, who will to her? Will the family even know they can send for us? And what will we do when we visit the sick? Will we talk of God’s merciful love, or will we have grown timid about God-talk? Will we speak of confidence in God’s presence and of the resurrection that arises from human death, or will we shy away from this desperate spiritual need of the seriously ill and dying? When will we lose sleep or weight because we have been consoling the desperately ill? When will the next Sister of Mercy die from caring for the sick?

I raise these questions, humbly and with compassion, not because I think my own life responds to them even minimally, and not because I think they admit of easy answers, but because they are the questions that haunt me whenever I reflect deeply on these aspects of Catherine McAuley’s life. I do not think our lives can be a mirror image of hers, any more than the ailments and desperations of the twenty-first century are a mirror image of the ailments and desperations of the nineteenth century in Ireland. But there is something permanent in Catherine’s tender personal care of the sick and dying: some true Gospel instinct and virtue that is a permanently valid call to us; a call of God to us, precisely as Sisters of Mercy; a call that is not rendered obsolete by the use of late twentieth-century language about self-protection or self-fulfillment.

Notes

[1] The other two works of mercy, mentioned in all the early Mercy sources, were the instruction of poor girls and the sheltering and mining of homeless young girls and servant women.

[2] In noting these medical advances and in discussing diseases elsewhere in this essay, I am dependent on information in the following sources: Frederick F. Cartwright, Disease and History (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1972); The Encyclopedia Americana; The Encyclopedia Britannica; The Oord Companion to Medicine, 2 vols., ed. John Walton, Paul B. Beeson, and Ronald Bodley Scott (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986); and John H. Talbott, A Biographical History of Medicine (New York: Grune and Statton, 1970).

[3] The first hospitals owned and operated by the Sisters of Mercy in Ireland were Mercy Hospital in Cork, opened in 1857, and Mater Misericordiae Hospital, opened in Dublin in 1861. In 1854 the Sisters of Mercy on Baggot Street took over management of the Charitable Infirmary on Jervis Street, Dublin.

[4] Anna Maria Doyle, Catherine Bym, and Frances Warde.

[5] Presumably Mary Ann Redmond left Baggot Street before September 8, 1830, the day Catherine went to the Presentation Convent on George’s Hill to begin her required novitiate prior to founding the Sisters of Mercy.

[6] Mary Clare Moore was the sister of Mary Clare Augustine Moore. Mary Clare entered the Baggot Street community in 1830; Mary Clare Augustine, in 1837. They were unrelated to Mary Elizabeth Moore who entered the community in 1832, and to whom reference is made later in this essay.

[7] R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History (New York: Harper Collins, 1993),907.

[8] In her volume on the Crimean War, Mary Angela Bolster, RSM, has well documented, through their letters and diaries, the perspective of the Irish sisters; the correspondence and annals in the Bermondsey archives of the Sisters of Mercy document the perspective of the Bermondsey sisters; and Florence Nightingale’s own papers and correspondence document her perspective on each group. It is not possible here to address this issue further, to discuss other clerical and governmental documentation related to it, or to analyze the causes of these contrasting experiences.

[9] Mary Clare Moore to Florence Nightingale, October 13, 1862 (Greater London Record Office HI/ST/NC2-V26/62). I have modernized some of the punctuation.

[10] The complete text of Catherine McAuley’s manuscript of the Rule is contained in Sullivan, Catherine McAuley and the Tradition of Mercy, 294—328. I have here presented Catherine’s original wording, without Daniel Murray’s insertion (after “pace”): “not stopping to converse, nor saluting those whom they meet.” I have also substituted “or three” for Catherine’s “etc. etc.” in her quotation of Matthew 18.20.

[11] These archives and manuscripts are located in Mercy International Centre, Baggot Street, Dublin.

[12] I have briefly discussed the significance of the practice of these three saints to Catherine’s own spiritual formation in “Catherine McAuley’s Spiritual Reading and Prayers,” Irish Theological Quarterly 57 (1991) 2: 124-146.

[13] Mary Elizabeth Harley actually died on Easter Wednesday, April 25, 1832.

[14] Bull Alley, encompassing several streets, was one of the worst slums in early nineteenth-century Dublin, as was the area around Townsend Street.

Works Cited

- Bolster, Evelyn [Mary Angela]. The Sisters of Mercy in the Crimean War. Cork: Mercier Press, 1964.

- [Carroll, Mary Austin]. Leaves from the Annals of the Sisters of Mercy. Vol. 2. New York: Catholic Publication Society, 1883.

- [Carroll, Mary Austin]. Life of Catherine McAuley. New York: D. & J. Sadlier, 1866.

- Courtney, Marie-Therese. “Cholera Ravages Limerick.” Sisters of Mercy in Limerick. n.p.: n.p., 1988. 38-42.

- Harnett, Mary Vincent]. The Life of Rev. Mother Catherine McAuley. Ed. Richard Baptist O’Brien. Dublin: John Fowler, 1864.

- McAuley, Catherine. The Letters of Catherine McAuley, 1827—1841. Ed. Mary Ignatia Neumann. Baltimore: Helicon, 1969.

- Meagher, William. Notices of the Life and Character of His Grace Most Rev. Daniel Murray. Dublin: Gerald Bellew, 1853.

- Ô’ Tauthaigh, Gearóid. Ireland Before the Famine, 1798-1848. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan. 1990.

- Rahner, Karl. “The Church of the Saints.” Theological Investigations. Vol. 3. Trans. Karl-H. Kruger. London: Darton, Longman, & Todd, 1967. 91-104.

- Rahner, Karl. “Parresia (Boldness).” Theological Investigations. Vol. 7. Trans. David Bourke. London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1971. 260-67.

- Scanlan, Pauline. The Irish Nurse: A Study of Nursing in Ireland…1718-1981. Nure, Manorhamilton, Co. Leitrim: Drumlin Publications, 1991.

- Sullivan, Mary C. Catherine McAuley and the Tradition of Mercy. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1995. This volume contains the texts of all the early biographical manuscripts referred to in this essay.

- Walton, John, Paul B. Beeson, and Ronald Bodley Scott, eds. The Oxford Companion to Medicine. 2 Vol. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

This article was originally printed in English in The MAST Journal Volume 6 Number 2 (1996).