This article’s title, referring to a specifically Catholic theological case for women’s leadership in the Church, may seem surprising.[1] After all, currently women cannot serve as priests, bishops or deacons in the Catholic Church. Despite increased speculation in both the Catholic and secular presses regarding the future of women’s leadership in the Church in light of the election of Pope Leo XIV,[2] in 2026, the persistent and significant gap between foundational Catholic theology and current Church operations is nearly incomprehensible. If Church practice were congruent with central elements of Catholic theology and Catholic social teaching, the Catholic Church would be at the forefront of promoting women’s well-being and women’s leadership commensurate with the ways it prizes men’s well-being and leadership. Limiting women’s leadership remains contrary to Catholic theology, deprives the Church of needed leadership, limits the attraction of membership in the Church for many, and mutes the Church’s social impact by serving as a counter-witness to the Gospel. Promoting women’s leadership would not only strengthen the Church internally but also make it a more credible and authentic witness to the Gospel in society, as is seen by analyzing the Synod on Synodality.

Before making the Catholic case for women’s leadership in the Church, it is necessary to define some terms. Leadership theories abound, and scholarship on leadership remains contentious and wide-ranging. For the purposes of this article, women’s leadership refers to the Catholic Church’s institutional capacity to foster women’s flourishing in positions of influence in the Church. The Church’s treatment of women contrasts strongly with Catherine McAuley’s understanding and practice of leadership and leadership development.[3] According to Mary Sullivan, Catherine’s method of leading other Sisters of Mercy included eight elements that effectively invited many other sisters into leadership and ensured continuity of strong leadership of the Sisters of Mercy after her death:

- her own good example

- her spoken and written words

- her affection and love

- her purity of intention

- her willingness to initiate, to venture into the unknown

- her trust in others’ capacity to grow and develop

- her emphasis on the community and its common purpose

- her cheerfulness, sense of humor, and self-effacement[4]

These eight elements of leadership development assume inclusion as a prerequisite for the ability to lead. Catherine established an inclusive environment that attracted other women to difficult, heartbreaking and often thankless work in serving the poor, sick and ignorant. At the same time, she developed others’ abilities to occupy official positions of leadership as the order grew and expanded, to the extent that she was confident in handing on the senior leadership of the Institute to others upon her death.[5]

It is noteworthy that women’s viewpoints and leadership styles are not uniform—women hold a range of political, religious and other commitments that inform their leadership and the policies that they advocate. Thus, the term “women” here includes people with diverse backgrounds and identities, including race, ethnicity, class, religion, age, sexual orientation, marriage status, and parenthood status. These and other aspects of women’s identities—as they intersect with gender identity—influence how women are perceived and treated, and the possibilities for their leadership. For example, women of color and women who are poor frequently encounter even more severe obstacles to leadership than do white, wealthy women.

Therefore, this article analyzes foundations for affirming women’s leadership in the Church that emerge from the Catholic tradition, understanding that particular commitments and contexts affect women’s leadership. In other words, simply because a woman occupies a formal leadership position does not mean she leads in a way that uplifts all women or matches the theology discussed here. The claim here is not that women are more capable than men as leaders; rather, the article provides a Catholic theological case supporting equity of opportunity for both women and men that holds the potential for contributing to the Catholic Church’s capacity to flourish in its mission. To make the Catholic case, the article first highlights two foundations in Catholic theology and then three principles in Catholic social thought that are particularly relevant.

Catholic Theological Foundations: Sacramental Imagination and Social Anthropology

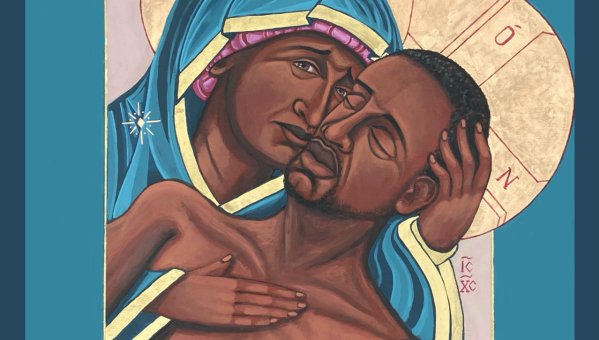

The Catholic theological case supporting women’s leadership is expansive. Given limited space, this article explores only two of the most compelling theological foundations: a Catholic sacramental worldview and social anthropology. When many Catholics first consider the sacraments, they initially name the seven official Catholic sacraments including baptism, Eucharist, marriage, last rites, confirmation, reconciliation, and holy orders. A sacramental worldview, however, includes not only the seven sacraments listed here but also an entire lens for interpreting how God relates to humanity in everyday life.

For Catholic theology, God’s love/God’s grace is always with us, and suffuses everyday life so that any experience can reveal God’s love (and therefore serve as a sacrament) if we are attentive enough to notice. According to theologian Michael J. Himes,

A sacrament makes grace effectively present for you by bringing it to your attention, by allowing you to see it, by manifesting it. Sacraments presuppose the omnipresence of grace, the fact that the self-gift of God is already there to be manifested…. Any thing any person, place, event, any sight, sound, smell, taste, or touch that causes you to recognize the presence of grace, to accept it and celebrate it, is a sacrament, effecting what it signifies.[6]

When we do wake up to God’s embrace in everyday experiences, we can experience sacramental moments many times throughout the day in both what we might consider overtly religious activities (e.g., through prayer and the liturgy) and also through ordinary or secular experiences. For example, when walking down the street we may observe a tree or other gift in creation and become aware that it has its origin in God. Or new and exhausted parents, whose crying baby awakens them in the night, may recognize they are awash in love for that child as God’s gift as they stumble out of bed to comfort her. Relationships with ourselves and other people, of course, are the primary way most of us encounter God in our ordinary lives. As Catherine McAuley, the Sisters of Mercy and many others emphasize, the face of Christ can be discerned most clearly through accompaniment with anyone in need.

The Catholic sacramental imagination affirms that the sacred emerges within the secular, in the midst of the messiness and complexity of what we commonly think of as “ordinary” life. Even life events that involve limits, which we would prefer to resist or avoid, may also reveal God’s constant love and accompaniment. Death, illness, personal challenges, political oppression and other suffering can be occasions to become aware of the constant love of God.[7]

The upshot of the sacramental imagination is that our actions to promote love, peace and human flourishing in our work, family, civic and other dimensions of our lives can express our awareness of God’s love. When the Church limits women’s leadership roles, it restricts how people imagine and encounter the love of God. A fuller revelation of God’s grace in what we term “sacred” and “secular” situations could occur if women were accorded the same leadership roles as men in order to be perceived as symbols of God’s love in the ways that men are.

A second major theological foundation undergirding the obligation to promote women’s leadership is the Catholic view of the relationship between God and humanity—and among all of us as a human family—commonly termed a social anthropology. Conducting a “clothing tags exercise” is one of the clearest ways to demonstrate this theological concept. When I conduct this exercise with groups, I invite each individual to take a moment to find the country where two or three items they are using or wearing right now were made. You might do this now by investigating the tag on your sweater or coat to identify the country in which the item was made. Participants quickly realize through this exercise that we often look at the size and the washing instructions on our clothing tags, but we frequently miss observing the place where those who crafted our clothing live. Moreover, we often fail to notice the countries of origin for other household items such as phones, computers, furniture, and appliances even though they are named on the items.

This exercise illustrates that each of us is connected right now to people all over the world who created the things we use. The quality of the workmanship of people all over the world affects how long our clothes or phones or computers will last; and what we pay for these goods (and from whom we purchase them) affects wages and working conditions of brothers and sisters all over the world.

The Catholic view is that we are necessarily interconnected. Our exercise demonstrates some economic interconnections, but we could also delve into our political, health, spiritual and other connections—even with people we will never meet directly across the globe. The everyday practice of reading the news, too, underscores the deep and abiding influence of political, religious and cultural leaders and movements. As Martin Luther King wrote in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” regarding his duty to become involved in civil rights, “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.”[8] A Catholic social anthropology underscores that it would be impossible to completely escape or distance ourselves from others’ joys, sufferings and experiences, even if this were our desire.

The Catholic theology of the human person acknowledges that each individual possesses free will and bears responsibility for their decisions and actions. These characteristics, however, exist within the context of social relationships, as we are all connected in the Body of Christ. Further, we are responsible for one another—not just our families, friends, and those we like—but also all of our brothers and sisters in the human family. The implication of a Catholic social anthropology to women’s leadership is that failure to support women’s leadership harms not only women (which is significant in itself) but also every single member of the Body of Christ. The reverberations of restricting women’s leadership negatively impact the quality of relationships among Catholics as well as between the Church and the rest of society.

Catholic Social Thought: Human Dignity, Common Good and Preferential Option for the Poor

Catholic social thought, as a dimension of the Catholic intellectual tradition, is based in part on the two theological foundations discussed above—a sacramental worldview and a social understanding of the person in community. As life in society is complex, Catholic social thought is an extremely wide field; this article addresses only the parts of Catholic social thought that are most pertinent to how we structure leadership and gender relations in the Church.

Catholic social thought comprises official magisterial teaching authored by Catholic popes and bishops on social issues, lived experience of faithful Catholics, analysis by theologians and other scholars, and other dimensions. Catholic social thought is accessible to all people of good will. While for Catholics, Catholic social thought enjoys deep resonance with life of Jesus, the saints and the theological tradition, it is possible that those who are not Catholic or Christian can come to the same conclusions and embody them even more fully than some formed in the Catholic tradition.

As an expression of the Catholic sacramental imagination and social anthropology, Catholic social thought is situated at the intersection of Church and world, sacred and secular; as such, it responds to the challenge of exemplifying Christ’s teachings in everyday life as responsible family members, citizens, workers, consumers and members of the Church. It considers how to realize the gospel’s ethic of holiness in the midstof the messiness and complexity of everyday life and the new problems and challenges posed by history.[9] We can analyze Catholic social thought from many angles, including its principles, documents, lives of holy women and men and scholarship about the above. Given space constraints, here let us focus on three of the oft-cited principles—human dignity, common good and preferential option for the poor—that provide a strong grounding for women’s leadership in the Church.[10]

We begin with the principle of human dignity, meaning that as human persons are made in the image and likeness of a good God (drawing from the account of creation from the Book of Genesis in which God blesses each part of creation by saying that “it was very good”), human worth and value are rooted in our identity as children of God. An individual’s value does not result from their personal capabilities. Each and every person possesses the same human dignity regardless of race, religion, sexual and gender identity, and other personal characteristics. Further, the dignity of each person persists despite her or his actions and sin; it is intrinsic or inherent to the person by virtue of being human.

The principle affirms that individuals possess different abilities, but we do have the same worth that requires social protection. There is no hierarchy of value among persons. For example, the person with Down’s syndrome who works in a grocery store and the Nobel-prize winning economist possess the same dignity; the person whose struggles with addiction make it difficult for them to work full-time and the highly-educated, well-paid corporate executive have the same dignity. While employers and society place differing value on their work and compensation, their dignity as human persons is exactly the same. Catholic social teaching stresses that a person’s treatment and environment must be commensurate with their human dignity. Although Catholic theology affirms women and men have equal, intrinsic worth as children of God, in practice the Catholic Church values men’s leadership, labor and other contributions more than women’s.

This understanding leads us to a complementary principle, the common good. Common good refers to the sum total of the communal conditions needed to uplift every human life and to protect each person’s human dignity. This principle is grounded in the Catholic understanding of human beings as social, exemplified above in the clothing tags exercise showing economic interdependence. The common good affirms that communities and society must protect each individual’s human dignity. The individual can only be as healthy as the community in which she or he lives, and the community’s health is impacted by the ways it promotes or diminishes the flourishing of its individual members. While it is clear that women’s lives are diminished when their intrinsic dignity as human persons is not appreciated and promoted, it is also the case that many men are not flourishing in this current construct, either. The principle of the common good emphasizes that when women’s lives and leadership are valued less than men’s, everyone in the Church suffers, as we are all interconnected.

How do we move beyond the current situation in which both women and men are harmed by the ways in which we ignore human dignity and fail to protect the common good? The principle termed “preferential option for the poor”applies here, in that it refers to placing priority on actions with and for the poor and vulnerable. The terms “poor” and “vulnerable” refer not only to the economically poor but also to anyone relegated to the margins of society, those who have limited access to participating and enjoying social goods, and those who have been pushed out of decision-making. Option for the poor insists that, because God’s love suffuses every dimension of life (sacramentality) and because we are connected in a web of relationships (social anthropology), people who are socially excluded and marginalized hold the greatest claim on everyone else’s time, attention, and resources—with the goal of eventual inclusion of all in the human family.

In addition to calling those with resources to action, the preferential option for the poor also includes an epistemological dimension, which prioritizes the perspectives and insights of those whose voices are typically muted or ignored. Those in the Church who typically experience more inclusion, in this case men, are obliged to work to view situations from the perspectives of those typically excluded from formal leadership roles, in this case women. Ultimately, however, learning from and incorporating these undervalued perspectives into decision-making is only possible if the circle is enlarged, so that it includes those previously excluded. Practicing the option for the poor would logically culminate in the full inclusion of women as leaders in the Church.

Synod on Synodality: Model of a Listening Church, with Limits to Women’s Leadership

The Synod on Synodality offers a partial vision of what the Church could look like when it exercises the preferential option for the poor by admitting those typically excluded from decision-making to a seat at the table. The Synod exercised the option for the poor (albeit imperfectly) in that it structured opportunities for increased dialogue with, and influence of, those whose concerns, insights, perspectives and leadership have been largely muted or ignored—including women.

There is a great deal to analyze in the entire Synod on Synodality, which began with local listening sessions throughout the globe in 2021 as part of a consultation process that included not only those ordained to ministry but the entire People of God. Unlike previous Catholic synods that only included bishops, Pope Francis directed that this one include non-bishop voting members, including some women.[11] The Synod meetings in Rome considered summaries of themes that emerged from reports from local, national and continental dialogues. About four hundred worldwide delegates contributed to the final document, which Pope Francis endorsed as part of his ordinary magisterium.[12] While the Synod officially concluded in October 2024, the work of synodality continues.

Aspects of the Synod on Synodality most relevant to women’s leadership in the Church include the following. First, the fact that Pope Francis and other Church leaders designed a systematic process to facilitate a listening Church and a model of collaborative leadership is truly historic. For the first time, women were voting members at the Synod. The Synod’s final document declared, “The way to promote a synodal Church is to foster as great a participation of all the People of God as possible in decision-making processes.”[13] Writing in the National Catholic Reporter, Jesuit priest Thomas Reese observed, “What is new here is a papally endorsed process that allows the laity [including women] to surface their views in a public way.”[14] The fact that the Synod occurred is a source of hope that synodality, which the International Theological Commission defines as “involvement and participation of the whole People of God in the life and mission of the Church”[15] will not be a singular event, but an ongoing style of Church leadership that lessens the force of hierarchical and patriarchal models.

Concerns about the ways the Church frustrates women’s leadership were documented throughout the entire Synodal process. The United States National Synthesis notes, “Nearly all [U.S.] synodal consultations shared a deep appreciation for the powerful impact of women religious who have consistently led the way in carrying out the mission of the Church. Likewise, there was recognition for the centrality of women’s unparalleled contributions to the life of the Church….. There was a desire for stronger leadership, discernment, and decision-making roles for women—both lay and religious….”[16] These concerns were not only expressed in the United States. Synthesis reports compiled by conferences from every single continent documented a desire that women’s roles and leadership be expanded in the Catholic Church. Despite myriad cultures and norms across the planet, all agreed that the leadership roles of women in the Church are too restrictive.

According to the final document, “Inequality between men and women is not part of God’s design…. The widely expressed pain and suffering on the part of many women from every region and continent, both lay and consecrated, during the synodal process, reveal how often we fail to live up to this vision.”[17] Despite these reports from every single continent documenting the importance of expanding women’s leadership in the Church, the final document only devoted one out of the one hundred fifty-five paragraphs to this topic. Eleven of the forty-five times women are mentioned occur in Paragraph 60, which is therefore worth reviewing in its entirety:

By virtue of Baptism, women and men have equal dignity as members of the People of God. However, women continue to encounter obstacles in obtaining a fuller recognition of their charisms, vocation and place in all the various areas of the Church’s life. This is to the detriment of serving the Church’s shared mission. Scripture attests to the prominent role of many women in the history of salvation. One woman, Mary Magdalene, was entrusted with the first proclamation of the Resurrection. On the day of Pentecost, Mary, the Mother of God, was present, accompanied by many other women who had followed the Lord. It is important that the Scripture passages that relate these stories find adequate space inside liturgical lectionaries. Crucial turning points in Church history confirm the essential contribution of women moved by the Spirit. Women make up the majority of churchgoers and are often the first witnesses to the faith in families. They are active in the life of small Christian communities and parishes. They run schools, hospitals and shelters. They lead initiatives for reconciliation and promoting human dignity and social justice. Women contribute to theological research and are present in positions of responsibility in Church institutions, in diocesan curia and the Roman Curia. There are women who hold positions of authority and are leaders of their communities. This Assembly asks for full implementation of all the opportunities already provided for in Canon Law with regard to the role of women, particularly in those places where they remain underutilized. There is no reason or impediment that should prevent women from carrying out leadership roles in the Church: what comes from the Holy Spirit cannot be stopped. Additionally, the question of women’s access to diaconal ministry remains open. This discernment needs to continue. The Assembly also asks that more attention be given to the language and images used in preaching, teaching, catechesis, and the drafting of official Church documents, giving more space to the contributions of female saints, theologians and mystics.

We see here an attempt to ground discussion of women’s leadership in the key dimensions of Catholic theology and social teachings, yet the final document does not take these foundations to their logical conclusions. Though the final document casts gender inequality as unacceptable, it does not imply that women and men should have equal opportunities for leadership or suggest new forms of leadership for which women may discern vocations, including the diaconate or ordination to the priesthood. Rather, the document suggests that all Church ministries available to women currently under Canon Law should be more widely encouraged and practiced, and that Scriptural accounts of women be more thoroughly included in the lectionary.[18]

Despite the consultative structure of the Synod and the pledge that it would involve transparency and accountability, the final 2024 document disappointed those who advocate for more expansive leadership roles for women, particularly in restoration of the female deaconate and the women’s ordination to the priesthood.[19] Restoration of the female diaconate alone would not sufficiently demonstrate men’s and women’s equal opportunity for leadership in the Catholic Church, but it does serve as a case study of the current situation. Please note the significant phrase—“restoration of the female deaconate,”—as both the New Testament and early Church documents include accounts of female deacons.[20] The final document does not declare the restoration of the female deaconate as an issue that cannot be discussed. However, many, including the Association of Catholic Priests, voiced their disappointment that Pope Francis removed discussion of women deacons from synod talks and instead relegated ongoing study of the possibility of the restoration of women to the diaconate to the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith. Other topics of ongoing study were assigned to mixed groups, the participants of whom are named publicly.[21] The Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, however, is composed entirely of ordained men and will submit its conclusions on the permissibility of women deacons by late 2025 (after this article’s submission). For those who advocate for the principles of human dignity, common good and option for the poor as foundations for Church operations, this process seems to be an exclusionary tactic that delays rather than facilitates an authentic process of discernment for the whole Church.

Reports of women’s responses to the Synod process frequently employ the word “hope” regarding the possibilities for women’s leadership in the Church.[22] It should be noted that Christian hope (based upon a faith-filled interpretation of possibilities in light of constraints) differs from optimism (based upon a strict appraisal of the facts). Hope for the Church’s future development in recognizing women’s full potential for leadership does not necessarily reflect an expectation that the Church will change but instead reflects faith, patience and perseverance. Hope rests on the sacramental imagination and faith that the work of the Holy Spirit is ongoing in everyday life even when results fall short of expectations.

Hope abounds for women’s full leadership in the Catholic Church. The project Discerning Deacons leads advocacy for women’s restoration to the diaconate, despite the frustrations of the Synod process and conclusions.[23] Further, Carolyn Y. Woo documents actions that display continued hope for the Church’s potential to embrace a wide range of women’s leadership positions in her 2022 book Rising: Learning from Women’s Leadership in Catholic Ministries.[24] She shows that, despite patriarchy and clericalism, women lead many Church ministries in schools, parishes and (arch)dioceses, the media, as well as institutional ministries such as Catholic Charities, Catholic Relief Services and Catholic hospital systems at all levels.[25] In addition, three women, Dr. and Sister Raffaella Petrini, FSE, Sister Yvonne Reungoat, FMA, and Dr. María Lía Zervino, were appointed in 2022 to the Vatican’s Dicastery for Bishops under the leadership of Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost (who would be elected as pope and assume the name Pope Leo XIV). Women’s participation in the Dicastery for Bishops is significant in that the Dicastery recommends future bishops globally.

The expectation, particularly in light of Pope Francis’ message accompanying the publication of the final Synod document that it be implemented immediately, is that the Synodal process will not be merely an event but initiate a new way of being Church. The synodal journey, which highlights communal discernment, continues. Cardinals Robert McElroy and Blase Cupich have proposed that the U.S. Bishops’ Conference would benefit from a Committee on Synodality that would increase accountability and ensure a more participatory and transparent process of decision-making in the U.S. Catholic Church.[26] This would involve, as the final synod document recommends, that bishops are held accountable to the communities they serve, implying greater lay and women’s leadership.

Women religious lead the way in embracing a synodal style of leadership, which many practiced well before the 2021-2024 Synod. The International Union of General Superiors conducted their assembly in May 2025 in the synodal style of inclusive dialogue and reflection. The meeting’s conclusions about fostering leadership among women bear a striking similarity to the eight elements of leadership development practiced by Catherine McAuley:

Transformational leaders… are those that seek to empower and encourage their members, always concerned with maximizing their potential. They also attempt to raise the consciousness of their members by leading them by example to transcend personal interests for the benefit of others. They are servant leaders who use less institutional power and less control, sharing their authority with others, as Jesus did.[27]

If these practices embraced by women religious were more widely employed through synodal processes, they could contribute to healing the Church and world.

Exclusion of women from significant and authoritative leadership roles in the Catholic Church (in addition to other factors, particularly the clergy sex abuse scandal) makes it more difficult to attract and retain members. Referring to the social context of the United States, Pew Research reported in 2025 that “Catholicism has experienced a greater net loss due to religious switching than has any other religious tradition in the U.S. Overall, 13% of all U.S. adults are former Catholics,”[28] having joined other religious communities or disaffiliating altogether from religion. Failure to promote women’s leadership limits the Church’s capacity to serve as a visible sacrament of God’s love. Further, it counteracts the Church’s witness as a credible advocate for women who suffer disproportionately from other social injustices Catholic social thought champions, which include the areas of vital need identified as Critical Concerns of the Sisters of Mercy—immigration, violence, environmental degradation, racism—as well as poverty and other social suffering.

Although the Catholic Church in practice is ambivalent at best about women’s leadership,[29] Catholic theology provides a strong foundation to undergird promotion of women to leadership positions equal to those held by men. Among other theological foundations, a Catholic sacramental vision encourages us to see God’s presence in everyday life in one another and through any life experience. A social anthropology emphasizes that we are all connected and there are no “others” unworthy of connection, support, and the opportunity to lead—all are part of the human family. Commitment to human dignity underscores the responsibility to ensure that society recognizes everyone’s inherent value in contributing to the Church. The common good implies the need to create just social structures and relationships in the Church, so that it more effectively promotes human flourishing for all people. And the preferential option for the poor implies an obligation to amplify the voices of those typically excluded, which benefits everyone. Catholic theology contains the foundations to advance the Church’s unity and to support women’s leadership in order to create a more just and inclusive future. It is hoped that as the synodal process of inclusive discernment is practiced more deeply and widely, the Church will recognize equality of leadership among women and men as congruent with central dimensions of Catholic theology and social teaching. If this occurs, the Church will contribute more fully to revealing the Kingdom of God among us which is already present and, at the same time, only partially realized.

[1] I thank Bernard Prusak and Ed Peck of John Carroll University, as well as the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities, for invitations to present papers on related topics in 2024 and 2023, respectively. This paper builds on those presentations as well as the chapter I co-authored with Catherine Punsalan-Manlimos, “Beyond Patriarchy? Women’s Leadership in Catholic Higher Education,” in Catholic Higher Education and Catholic Social Thought, ed. Bernard Prusak and Jennifer Reed-Bouley (Mahwah, New Jersey: Paulist Press, 2023).

[2] See, for example, illustrative articles from varied United States news sources: Patricia Mazzei, “On the Role of Women in Church Leadership, Leo Has Followed Francis’ Lead,” New York Times, May 9, 2025; Jason DeRose, “Women who want to be Catholic deacons are hopeful about Pope Leo XIV. Here’s why,” National Public Radio, June 10, 2025; andChristopher Lamb, “A bridge builder and quiet reformer. How Pope Leo will lead the Catholic Church,” CNN, May 12, 2025.

[3] Mary Sullivan, “Catherine McAuley’s Methods of Leadership Development,” MAST Journal: The Journal of the Mercy Association in Scripture and Theology (2014: 22/2).

[4] Mary Sullivan, “Catherine McAuley’s Methods of Leadership Development,” MAST Journal: The Journal of the Mercy Association in Scripture and Theology (2014: 22/2). See also Mary Wickham, “Storms and Teacups: An Acrostic on the Leadership of Catherine McAuley,” ISMA Journal Listen, (2004: 22/1) and reprinted here: Mary Wickham: Poetry and Spirituality Website.

[5] See, for example, Denise M. Colgan and Doris Gottemoeller, Union and Charity: The Stories of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas (Silver Spring, Maryland: Institute of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas), 2017.

[6] Michael J. Himes, Doing the Truth in Love: Conversations about God, Relationships and Service (New York: Paulist, 1995), 108.

[7] This does not imply that God causes suffering in order to awaken us to our need for God; rather, these experiences of vulnerability hold the possibility of opening us to be more receptive to God’s love.

[8] Martin Luther King, Jr., “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” 1963, accessed at https://www.africa.upenn.edu/Articles_Gen/Letter_Birmingham.html

[9] I am indebted to Bernard Prusak for framing this understanding.

[10] For descriptions of the other principles, see the website of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

[11] See Salvatore Cernuzio, “Synod: Laymen and laywomen eligible to vote at General Assembly,” Vatican News, April 26, 2023 and Carol Glatz, “Pope appoints hundreds to attend Synod of Bishops on Synodality,” United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, July 7, 2023.

[12] Justin McClellan, “Final synod document is magisterial, must be accepted, pope says,” National Catholic Reporter, November 26, 2024.

[13] Pope Francis, For a Synodal Church: Communion, Participation, Mission: Final Document, November 24, 2024, paragraph 87.

[14] Thomas Reese, “A welcoming Church enhances communion and participation,” National Catholic Reporter, October 24, 2022.

[15] International Theological Commission, Synodality in the Life and Mission of the Church, March 2, 2018, paragraph 7.

[16] United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, National Synthesis of the People of God in the United States of America for the Diocesan Phase of the 2021-2023 Synod: For a Synodal Church: Communion, Participation, and Mission, September 2022, p. 8.

[17] Pope Francis, For a Synodal Church: Communion, Participation, Mission: Final Document, November 24, 2024, paragraph 52.

[18] The ways in which the Synod document discusses women are similar to trends in Catholic social teaching more generally. For example, in Laudato Si’, paragraph 14, Pope Francis urges that “[w]e need a conversation which includes everyone” about environmental degradation and climate change, for “the challenge we are undergoing and its human roots, concern and affect us all.” Unfortunately, the document minimizes women’s scholarly and pastoral contributions to the analysis. Christiana Zenner points out that, despite the above invitation to inclusive dialogue, “by disregarding current scientific approaches to the intersection of gender and ecology, neglecting to cite female scholars and omitting references to the work of women religious, Laudato Si’ and Laudate Deum perpetuate ‘the women problem,’ which is to say they omit them.” However, Zenner notes that Laudato Si’, unlike most ecclesial social teaching, notes women’s disproportionate burden as a result of climate change and environmental degradation. Christiana Zenner, “’Laudato Si’ called all to climate action, but omitted women from the conversation,” National Catholic Reporter, May 27, 2025.

[19] On restoration of the female deaconate, see Carol Glatz, “Synod on Amazon opened the way for synod on synodality, cardinal says,” National Catholic Reporter, October 16, 2024.

[20] When the final Synod document discusses “restoration of the permanent diaconate,” it refers to Vatican II reforms allowing male deacons, not the restoration of the initial Church practices of recognizing women as deacons.

[21] Christopher White, “The Vatican synod agenda calls for transparency. But on women deacons, it’s lacking,” National Catholic Reporter, July 31, 2024; Sarah Mac Donald, “Priests ‘extremely disappointed’ by removal of women deacons from synod talks,” The Tablet: The International Catholic News Weekly, October 15, 2024.

[22] See, for example, Christopher White, “Women deacons movement hopes for concrete proposals in next synod stage,” National Catholic Reporter, October 13, 2022; Joyce Meyer, “UISG assembly: Synodal signs of hope for women religious, future of Church,” National Catholic Reporter, June 11, 2025; Heidi Schlumpf, “Activists frustrated yet hopeful after synod punts on women deacons,” National Catholic Reporter, November 11, 2024; Thomas Reese, “Synod ends with disappointment and hope,” National Catholic Reporter, November 7, 2024.

[23] See Discerning Deacons at https://discerningdeacons.org

[24] Carolyn Y. Woo, Rising: Learning from Women’s Leadership in Catholic Ministries (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis, 2022).

[25] Claire Giangravé, “Meet Sr. Nathalie Becquart, the woman who is helping reshape the Catholic Church,” National Catholic Reporter, December 9, 2021. Another significant appointment was that of Sister Alessandra Smerilli, FMA, as the Secretary of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development in 2021.

[26] Christopher White, “Cardinals Cupich and McElroy call on U.S. bishops’ conference to be more synodal,” National Catholic Reporter, October 27, 2024.

[27] Joyce Meyer, “UISG assembly: Synodal signs of hope for women religious, future of Church,” National Catholic Reporter, June 11, 2025.

[28] Pew Research Center, “Religious Switching.” For a more extended analysis, see Bob Smietana, Reorganized Religion: The Reshaping of the American Church and Why It Matters (New York: Worthy Books, 2022).

[29] Kathleen Bonnette, “How Misogyny prevents Catholics from accepting women’s leadership,” America Magazine, November 21, 2024.

image: Jennifer Reed-Bouley at the 2023 Catholic Social Tradition Conference

via the Catholic Higher Education and Catholic Social Thought