The theme for our reflections is “Sowing Hope: Embracing Cultural Diversity,” and I have been asked to focus on Catherine McAuley’s legacy as it relates to this theme.[1] I hope to do this by examining not only Catherine’s hospitality, but also the Christology that shaped her behavior.

Those who have visited Dublin are aware of the strikingly beautiful Georgian doors which are the most prominent visual feature of the dwellings built in Dublin in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Some of you may have even seen the poster entitled “The Doors of Dublin.” Today, I would like to focus on just one of those doors, not on its architectural function, shape, or color, but on its spiritual meaning as a metaphor for the woman who built this door and as a metaphor for the conception of Jesus Christ which informed her mind and heart as she opened it: The front door of the House on Baggot Street.

In the Derry Large Manuscript, which records the memories of Mary Ann Doyle, we read of an incident that occurred at that door in 1829. Perhaps this story can illustrate in narrative form some of the depth of welcoming and embracing that we wish to explore:

In the beginning of this year a circumstance occurred which strongly demonstrated the benefit which the institution was calculated to produce. Late one evening in answer to a violent ringing, the door, secured by the chain, was cautiously opened and admitted the flushed face of a very young girl, who implored a shelter for the night saying she had traveled on foot from Killarney and knew no one in Dublin.

The wild glare of her large dark eyes, the disorder of her hair and dress naturally excited unfavorable suspicions, but as she was evidently in great distress our dear charitable foundress would not refuse her relief, so she was brought into the hall and had some bread and milk given her. She then, though very incoherently, for she was stupefied with fatigue, hunger and terror, told her name and how on account of a quarrel with her severe step-mother she had run out of her father’s house; when not knowing in what manner to retrieve this imprudence she had proceeded on to Dublin, where she had no friends and no resources.

In the Country she had heard of the Sisters of Charity, and conceiving that the very fact of her necessities would be a sufficient recommendation, she got herself directed to Stanhope Street, where of course she was denied admission, but as some consolation was told that in Baggot Street. A Miss McAuley had a great house where all sorts of people were let in; for thus did even the pious and charitable speak of our poor institution then.

She was not exactly taken into the house that night, but a safe lodging was procured for her in Little James’s Street. And Miss Doyle having recognised her father’s name as that of a professional gentleman who had married a second time to one that was accused of much harshness toward his elder children it was resolved to admit her next day and make due enquiry as to her identity. This satisfactorily proved, as well as the truth of her story in other particulars, she was protected ’till a situation was procured for her a few months after; but though she conducted herself well in it she did not remain long, for her father forgave her and brought her home. (Sullivan, ed. 50)

It is all too easy to slip over the extraordinary elements of this story—until we start thinking about our own front doors. It is late at night, we’re not expecting anyone, the door is locked, and we’re ready for bed. Then the doorbell rings violently, and a total stranger with a wild look in her eyes begs for shelter for the night. We have our “unfavorable suspicions” of her. She has already gone to the door of some other religious folk in town, but they have cautious rules against spontaneous admission, therefore they have directed her to us.

Is this the sort of scene Jesus has in mind when he says: “I was a stranger and you welcomed me”? The oldest woman in the House on Baggot Street believes it is. She realizes the girl’s great distress, she will not refuse her, she brings her in, she gives her some bread and milk, and she listens to her incoherent account of running away from Killarney in southwest Ireland and walking 190 miles to Dublin. The woman takes the girl to a safe place nearby for the rest of the night (so as not to disturb the sleep of the other young girls and women sheltered in the house), and then in the morning she welcomes her as one of the community, promises to protect her from harm, teaches her some useful skills, and a few months later gets her a job as a servant in a trustworthy household.

All this may seem like a one-of-a-kind event—until one remembers that this is the great house on Baggot Street where, according to the Sisters of Charity on Stanhope Street, “every sort of people were let in,” and until one remembers that the older woman is Catherine McAuley. She is the woman who once found a demented woman alone and impoverished in a hovel and brought her home to Coolock; who once found an orphaned child thrown into the street and brought her home; who once during the 1832 cholera epidemic wrapped an orphaned infant in her own shawl and brought her home, to a little bed in her own room; and who in the course of fourteen years on Baggot Street welcomed “more than a thousand” such strangers through her Georgian front door—often sixty at a time (Sullivan, ed. 127).

In one of his many essays on the mystery of the Incarnation, Karl Rahner speaks of Jesus Christ as the finite door which the infinite God has become, in order “to open a passage into the infinite for all the finite, within which he himself has become a part—to make himself the passage and the door, through whose existence God himself [becomes] the reality of nothingness.” In the Incarnation, God creates this holy door of welcome by “taking on” our humanity, and God “takes on” our humanity “by emptying” God’s self into the humanity God has taken on (Theological Investigations 4: 117). Elsewhere Rahner says that in order to become “the portal and the passage” of our abundant and unconditional at-homeness, the Word of God “creates the human reality [of Jesus] by assuming it, and assumes it by emptying himself” (Foundations 226). The door of our humanity, in the humanity of Jesus, is thus the very place where God asserts the irrevocable knocking of God’ s own self-surpassing presence and where we embrace and are embraced by God’s self-emptying love, Here in Jesus Christ the Word is made flesh and dwells among us in the one unique opening of “God’s self-renunciation and self-expression into what is other than” God’s own self—into the “strangers” that we are (Theological Investigations 5: 178).

The mystery of God’s kenotic presence in the humanity of Jesus, and of God’s welcoming of us in and through the portal of that gracious self-emptying is very difficult to grasp, and Rahner’s words as well as mine are only fumbling approaches to the reality of God’s embrace of our diversity. But even these words are enough to make us alert and eager when the figurative doorbell rings, and we are invited to open ourselves to the other and to otherness.

Jon Sobrino defines such moments as ones in which we ourselves are called to adopt “a real [and double] kenosis, that is, a life of voluntary poverty and an attitude of solidarity”: A willingness to be “lessened,” to be self-deflated by our own self-emptying into the situation of the other, and then to assume, from below, a stance of partisan solidarity with that other in his or her very diversity (The True Church 109, 148, 150). In such moments we are asked, after the example of God in Jesus, to welcome the stranger at our door.

If we think back on the example of Catherine McAuley and the girl from Killarney, we have much to learn from this metaphor of her unhesitating, self-humbling hospitality. First, she opens the door (she does not just peek through the curtains); second, she sets aside her suspicions; third, she offers the comfort of a chair and food; then she listens carefully to the stranger’s story and withholds judgment about its validity; and finally, she offers space in which the girl can be and become herself. It was of such girls that Catherine had dreamt, even when she lived with the Callaghans at Coolock House. As the Limerick Manuscript notes:

She took great delight in projecting means of affording shelter to unprotected young women. She had then no expectation of the large fortune which afterward was hers, but she fancied that if she had a few hundreds at her disposal, she would hire a couple of rooms and work for and with her protégées; the idea haunted her very dreams. (Sullivan, ed. 144-45)

For Catherine saw in every stranger at the door, in everyone who was different from herself, in every person, the hidden presence of Christ, the approaching and approachable self-utterance of the near but distant otherness of God. That is why she insisted that no one was to be kept waiting at the door. When Mary Clare Moore compiled the first collection of Catherine’s Practical Sayings in August 1868, she sent her compilation in draft form to other houses of the Sisters of Mercy to test its completeness and accuracy. In the Bermondsey Annals for 1868, Clare tells us that

Nothing was remembered additional, except the wish which our revered Foundress had expressed, that those who came on business, or even visitors to the Convent and the poor, should not be kept waiting either at the door or in the Convent longer than necessary, as she had noticed negligence on that point in some of the Communities. (Sullivan, ed. 33)

In the book of Exodus the voice of God sends this command to the people of Israel through the prophet Moses: “You must not oppress a stranger; you know how a stranger feels, for you lived as strangers in the land of Egypt” (Exodus 23:9). Certainly Catherine’ s human empathy for strangers, for those out of their own cultural homes, was nurtured by her own experiences as a stranger, by her own feelings of cultural diversity: when she lived with her mother whose religious sensibilities were so different from her own; when she lived with the somewhat bigoted Armstrongs; when she felt alienated from some of the religious views of the Callaghans and of her brother and brother-in-law; when she had to do business with Matthias Kelly, the parish priest of Saint Andrew’s who “had no great idea that the unlearned sex could do anything but mischief by trying to assist the clergy, while he was prejudiced against the foundress whom he considered a parvenue” (Clare Augustine Moore, “Memoir,” in Sullivan, ed. 208). Her empathy was also nurtured when “the higher rank of Catholics” in Dublin “sneered at her as an upstart, [and] as uneducated” (“Memoir,” in Sullivan, ed. 203); when she lived fifteen months with the cloistered and rigorous Presentation Sisters; when, later, she had to negotiate for a year and a half with Walter Meyler, the parish priest who refused to give her a regular chaplain for the sixty women and girls sheltered in the House of Mercy, even though he had at the time eight full-time curates on his parish staff; and when she was wrongfully humiliated by a lawsuit against her in Kingstown because she could not pay a £470 bill for the renovation of the coach house and stable she had donated for a school for poor girls—an expense the parish priest had initially assured her he would arrange to cover. Because Catherine herself was often the culturally diverse “outsider,” she knew what it felt like to be different, to be a stranger in an apparently alien place.

Yet the primary motivation for Catherine’s hospitality to strangers, her searching for them and her warmhearted welcoming of them into her own space and life, was not her own personal experiences of being left out, but her conviction about the living presence of Christ. The account of the Last Judgment in Matthew 25 was a very important scriptural text for her; she quotes from it twice in the opening chapters of her Rule: “Amen, I say to you, as long as you did it to one of these my least brethren, you did it to me” (Matthew 25:40). She does not quote the words of the sentence, “I was a stranger and you welcomed me” (Matthew 25:35); rather, she enacts the meaning of this sentence in the very shape of her life and of the community she created.

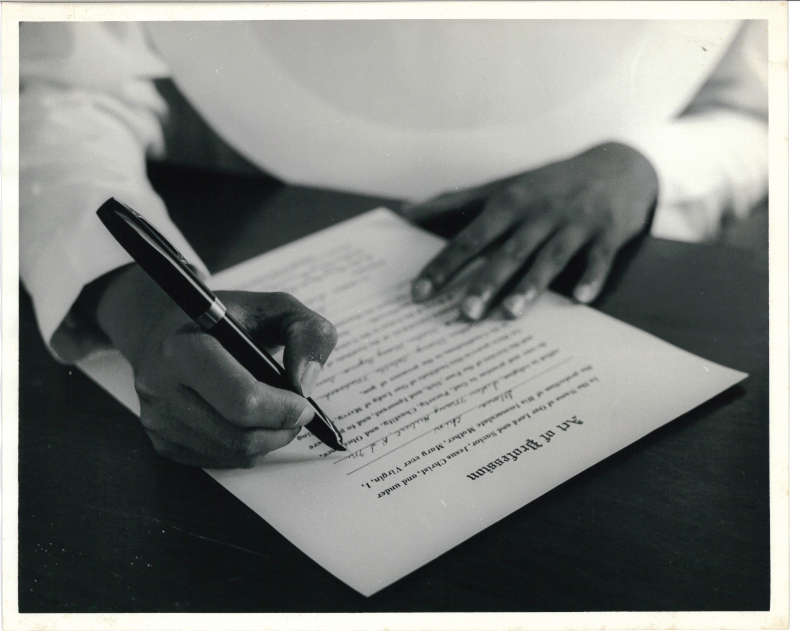

The original Rule of the Sisters of Mercy is a document handwritten by Catherine McAuley herself and slightly revised by Archbishop Daniel Murray of Dublin, Chapter 4 is devoted to welcoming distressed women into the House of Mercy. During her lifetime Catherine did most of the daily admitting of these girls and women herself. In this wise and thoughtful chapter she lays down the simple procedures for welcoming strangers into this House she had built for them and later expanded on Baggot Street. In paragraph three she writes:

3rd Although it must ever be considered a general rule to require suitable testimonials as to character and distress, yet there are some who have a strong claim for protection who could not obtain them. The Daughters of reduced tradesmen, who were not practically instructed in religion or known beyond the humble circle of their Parents’ home, should be admitted on the recommendation of a pious orderly woman, who had lived some years in the same neighbourhood; and they should be allowed to remain in the House untill practised in servitude,[2] and entitled to character from the Institution. (Sullivan, ed. 299-300)

One of the “evident mistakes” Catherine discovered in the confirmed Rule after it was returned from Rome in August 1841 was, to her mind, a serious alteration of this paragraph.[3] The very limitation which she had strenuously sought to avoid—namely, the referral of admissions decisions about strangers to nonresident personnel, with the consequent delay in providing shelter—was now inserted, presumably by someone in Rome. Into Catherine’s sensible and qualified provision that “Although it must ever be considered a general rule to require suitable testimonials as to character and distress, yet … the daughters of reduced tradesmen … should be admitted on the recommendation of a pious orderly woman,” the following wording was now inserted after “testimonials”:

And particularly that of the Parish Priest, concerning their character and poverty, nevertheless there are some deserving of assistance, though they cannot procure them. Still, about even these, the Parish Priest shall always be consulted, in order the better to know their dispositions, for the guidance of Superiors. But with this precaution, the daughters of reduced tradesmen…may be admitted…. (La Regola 12)

Whoever made this alteration may not have remembered that the text is talking about the admission of distressed women and girls into the House of Mercy, not about the admission of candidates into the religious community (Sullivan, ed. 279—80).

It will be a source of considerable consolation for some readers to learn that Catherine abhorred nonresident committees! Especially in regard to admissions into houses of refuge. What she particularly minded was the loss of spontaneous decision-making and the blind disregard for the immediate situation of the person at the door. According to the Derry Large Manuscript, she visited the House of Refuge of the Irish Sisters of Charity on Stanhope Street while Baggot Street was being built, but:

The more information she acquired concerning the government and general management of the House of Refuge the more she became convinced that the principles on which it was conducted were utterly incompatible with her design. The only consequence of these visits was therefore to confirm her in her resolution never to admit the interference of a non-resident committee, and never to close the doors of the institution against anyone because they had experienced its protection before. (Sullivan, ed. 46)

While at Coolock, Catherine had seen one “poor girl whose virtue was in danger” denied admission into a House of Refuge because the committee who made these decisions was not scheduled to meet. According to the Limerick Manuscript, Catherine never forgot this unfortunate circumstance, and she was determined to take “the most effectual precautions against the possibility of such a calamity” (Sullivan, ed. 144).

Catherine McAuley’s hospitality was chiefly, though not solely, preoccupied with those in need—with distressed women and girls who came to the door for shelter and protection, with the desperately poor and sick who had no one to visit them, with orphaned children who had no one but her to give them a home. But in a larger sense, Catherine’s whole personality was a self-emptied, hospitable place of welcome for everyone she encountered. Clare Augustine Moore says of her: “Even to the last she would not allow the least ceremony to be used toward her. She was with us precisely as my own mother was with her family, or rather we used less ceremony than was used at home” (“Memoir,” in Sullivan, ed. 206). Clare Augustine also reports the opinion of Judge Fitzgerald’ s mother whose servant, having temporarily left her child in Catherine’s care—after some pleading on Mrs. Fitzgerald’s part—then secretly married and sailed off to America. When Mrs. Fitzgerald came in embarrassed indignation to tell Catherine about this turn of events, “she was heard with so much kindness and calmness and found that excuses were offered for the fugitive.” She later said of Catherine: “‘ She made me feel… what real charity and real religion is”‘ (“Memoir,” in Sullivan, ed. 211)

Catherine offered the same gracious empathy to stagecoach drivers, poor boys who carried her luggage, bishops who visited Baggot Street, and to the youngest, most inexperienced postulants. If one were to ask her to choose her name for the virtue implied in what we call “embracing cultural diversity” her one word would probably be courtesy. She would not mean superficial politeness, that may sometimes mask coldness and inhospitableness, but rather genuine respect for and generous consideration of others: the kind of thorough courtesy that creates a large space for the differences between ourselves and others, and that honors their otherness and welcomes it into a deeper unity. For Catherine such courtesy is the result of charity and humility: the consequence of taking to heart Jesus’ command, “Love one another as I have loved you” (John 13:34; Rule 8, in Sullivan, ed. 303), and of realizing that humility of mind and heart is “the surest mark of true servants of Christ” (Rule 9.1, in Sullivan, ed. 305).

According to Clare Augustine Moore, the House on Baggot Street served for a time as a soup kitchen for the poor of Saint Andrew’s parish: “There was soup to be made for a hundred, sometimes more, and they had to pass through the office down to the dining hall in squadrons, and this by a wooden staircase now replaced by stone, so there was work and dirt and discontent, as well as derangement of the office business and inconvenience in the management of the House of Mercy” (“Memoir,” in Sullivan, ed. 209). It is evident that Clare Augustine wasn’t too keen on this much “cultural diversity,” but Catherine McAuley was. Even in these circumstances Catherine would say: “Our mutual respect and charity is to be cordial; now ‘cordial’ signifies something that revives, invigorates, and warms; such should be the effects of our love for each other” (Practical Sayings 5).

Any group—whether it is a college community, religious congregation, group of friends, or a nation—seeks to identify the unity which gives it meaning and purpose as a group. Indeed, every person seeks to have such unity and integrity within herself or himself in order in fact to be a self. The problem with unity—whether it is personal unity or group unity—does not lie in seeking and protecting it, which must occur, but rather in correctly naming its depth and breadth, and the consequent limits to diversity which the unity will require. To speak of “embracing diversity” is not therefore to speak of unlimited diversity without unity, or to deny the reality of the unity into which the diversity is welcomed, but rather to define properly the essential and authentic unity of the community who are doing the embracing, and thereby to define properly the limits to the diversity which the community can embrace. If a group defines its unity as fidelity to and advancement of God’s love and truth, then its limits to diversity will be wider and more open than if it defines its unity as the economic advancement of blond-haired Republican Christians who are under forty!

While Catherine McAuley defined the religious community who lived on Baggot Street, and in all future houses of the Sisters of Mercy, as Roman Catholic women who vowed to live in voluntary poverty, celibacy, obedience, and the service of the poor, sick, and ignorant, she did so in the context of a deeper and wider unity: fidelity to the merciful love of God for all God’s people. Hence the material and spiritual space inhabited by her religious community belonged not exclusively to the religious community but to all those diverse men, women, and children who were, knowingly or unknowingly, the recipients of God’s merciful love. Indeed she defined this larger unity precisely in terms of the indwelling presence of the Spirit of Christ in all those she encountered—at the door, in the streets, on country roads, in hospitals, in the hovels of the poor, wherever human faces presented the Christ of Matthew 25 for her response.

The “union and charity” which she so ardently wished to see flourish among her sisters in community and about which she spoke so earnestly on her deathbed—”May they live in Union and Charity and May we all meet in a happy Eternity” (Sullivan, ed. 242)—was not to be restricted to them alone, but was to include all who came within the multiple spheres of their lives—no matter how different they were from the Sisters of Mercy—so long as the bond of mutual trust in God’s merciful love could be maintained.

For Catherine had such confidence in the providential mercy of God that she could graciously welcome and patiently accommodate to the presence and needs of those who were different from herself—whether it was the little child, Mary Quinn, who sat between Frances Warde and herself at the Baggot Street dinner table (Sullivan, ed. 97), or the abandoned Poor Clares whom she welcomed into the Limerick community, or the Anglican professor from Oxford, Rev. Dr. Edward Pusey, who visited her at Baggot Street and then “invited himself” to a profession ceremony (Neumann, ed. 350-51), or Bishop Patrick Kennedy of Killaloe who was, in her view, “no great patron of nuns” (Neumann, ed. 298), or the young former Carmelite who entered Baggot Street and kept her eyes downcast for weeks, even in Catherine’s presence (Neumann, ed. 312), or Mary Clare Agnew of Bermondsey who was afflicted with “self-importance” and “fond of extremes in piety” (Neumann, ed. 352, 354), or any of the Sisters of Mercy who were so much younger than she and often so different in temperament from herself. In all these circumstances Catherine created a wide and generous space of courtesy and love. Her letters often contain a lovely sentence about people whom she came to know better, a sentence in which the burden of any hesitancy in her welcoming is placed squarely on her own inadequate perception: “I did not see her fully before” (Neumann, ed. 308).

It is not that Catherine set no limits to or had no opinions about what was tolerable diversity, but that her decisions not to accept what was different were based solely on fidelity to receiving and extending the mercy of God. She did not accept the schismatic Crottyites’ deluded attempt to divide and destroy the church in Birr, but she waded through mud and snow to visit them and to explain to them Paul’s description of charity in 1 Corinthians, chapter 13 (Neumann, ed. 288). She did not accept, in negotiations with Walter Meyler, that the poor women and girls sheltered in the House of Mercy should be denied the help of a regular and consistent sacramental minister, but on the day of her death she begged his pardon “if she ever did or said anything to displease him” (Sullivan, ed. 243). She did not accept Mary Angela Dunne’ s indirectly expressed suggestion that, for lack of postulants, the Charleville foundation should dissolve, and close down their works of mercy, but she wrote Angela an encouraging letter—”Are not the poor of Charleville as dear to [God] as elsewhere?” (Neumann, ed. 106-107)—and nine months later she spent ten days in Charleville, on route to Limerick in September 1838. Of this visit Catherine wrote: “I found I could be more useful there than perhaps I had ever been. There was danger of all breaking up, and my heart felt sorrowful when I thought of the poor being deprived of the comfort which God seemed to intend for them. I made every effort and, praised be God, all came ’round” (Neumann, ed. 138). Whenever Catherine could not accept, because of God’s merciful mission in Christ, what seemed to her contrary to that merciful intent, she tried to do so with love and respect, with patience and an offer to help, appealing to that deeper unity of God’s love which embraces all people.

In conclusion, if I were to summarize in the broadest terms Catherine McAuley’s embrace of cultural diversity and her legacy of hospitality to strangers, I would have to say that:

- She did not narrowly define the love of God or the unity to which we and our neighbors in this world are called.

- She did not misname differences or see cultural variations as obstacles to that unity.

- She did not use adversarial language to describe these differences.

- She did not cling to her own distinctiveness or to her own personal preferences or nonessential customs.

- And she did not regard her friendship with God as something to be coveted or exploited for herself alone.

Rather:

- She emptied herself of the comfort of her former way of life.

- She took the form of a servant in her human context.

- She extended her affectionate embrace to otherness.

- She opened her door to strangers.

- She welcomed them.

- She learned from those who were different and left them whole in their Godly difference.

- She humbled herself before all human forms.

- And she followed, as best she could, the example of Christ, who became obedient to God’s wide and merciful love of all humankind, even to the point of death, even death on a cross.

If we wish to sow the seeds of real hope in our world, I think Catherine McAuley would say: This is the way we must do it—one person at a time: one answering of the figurative doorbell, one opening of the figurative door, one embrace of the stranger, one welcoming of the other, one sharing of our bread and milk—one person at a time.

Notes

[1] This paper was presented as the keynote address at the Annual Meeting of the Mercy Higher Education Colloquium at St. Xavier University in Chicago on June 15, 1996.

[2] By “servitude” Catherine means employment as a servant, especially in domestic service. This meaning of the word was common in the nineteenth century, but is now rare or obsolete.

[3] The Rule and Constitutions of the Sisters of Mercy as confirmed in Rome in 1841 was an Italian translation of the text Catherine McCauley had submitted. Hence the published copy she received back from Rome was in Italian. This excerpt is translated into English.

Works Cited

La Regola e Le Costituzioni della Religiose nominate Sorelle Della Misericordia. Rome: Propaganda Fide, 1841.

McAuley, Catherine. The Letters of Catherine McAuley, 1827-1841. Ed. Mary Ignatia Neumann, RSM Baltimore: Helicon, 1969.

________. A Little Book of Practical Sayings, Advices, and Prayers of our Revered Foundress Mother Mary Catharine [sic] McAuley. Ed. Mary Clare Moore, RSM. London: Burns, Oates and Co., 1868.

Rahner, Karl. Foundations of Christian Faith. London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1978.

________. “Christology within an Evolutionary View of the World,” in Theological Investigations. Vol. 5. Trans. Karl-H. Kruger. London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1966. 157-192.

________. “On the Theology of the Incarnation,” in Theological Investigations. Vol. 4. Trans. Kevin Smith. London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1966. 105-120.

Sobrino, Jon. The True Church and the Poor. Trans. Matthew J. O’Connell. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1984.

Sullivan, Mary C. Catherine McAuley and the Tradition of Mercy. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1995. The texts of the early manuscripts cited in this paper are contained in this volume.

This article was originally printed in English in The MAST Journal Volume 6 Number 3 (1996).