I was first introduced to the phrase “thin places” during a lecture on religious life by Sister Marie McKenna.1 A “thin place” is a sacred space where the distance between heaven and earth seem to collapse, and we’re able to catch a glimpse of the divine. These places can be either physical spaces or places of transition such as a doorway, gate or seashore.

Vatican II was a transitional era for Christians. By exploring the theologies among the Vatican II participants, we might be better able to understand how the past intersects with the present and allows the future to unfold.

Therefore, I will offer some reflections on how “thin places” might pave the way for a renewed theology of the Church. Prior to examining the Vatican II theologians, I believe a brief investigation of the origin of the thin place concept to be helpful.

Thin Places: An Ancient Concept

We are not sure where the term “thin places” originated, but it is an ancient term with biblical roots. “Thin places” are also deeply embedded in Ireland’s mythology. The Celtic people arrived in Ireland around 500 B.C., but the idea of sacred places was already well established. The pre-Celtic people identified both tombs and wells as sacred sites.

For example, the Newgrange Tomb was thought to be thousands of years old because of its spiral carvings on the surface of the tomb. These carvings were common symbols used by the pre-Celtic people. An opening in the tomb allowed the gods to move in and out to visit their followers. The Celtic people believed these structures were built by the gods and goddesses who inhabited the land prior to them.2

Meeting the divine in sacred spaces and their natural manifestations are also found within scripture. The Israelites traditionally met Adonai in the temple, but God was always watching over them. In the Exodus story, the Israelites were safely led out of Egypt by a cloud during the day and a fire by night (Ex 14:19-21).

A similar story of God guiding the people appears in the New Testament where Jesus meets his disciples on the road to Emmaus (Lk 24:27-35). In both stories, we are able to catch glimpses of the mysterious and divine.

Wells

A second “thin place” for the Irish people were wells. They were common throughout Ireland and had deep religious and spiritual meaning. The water in the wells bubbles up and some of the water cascades to the ground. At this point, the water and the earth merge to form one identity. This merger of elements symbolizes their oneness with the divine.

Later, Christians identified wells as sources of healing and new life. The story of Jesus’ meeting with a Samaritan woman at a well is an example of this tradition (Jn 4:4-16). In John’s gospel, Jesus came to a Samaritan town, sat down near Jacob’s well and asked a Samaritan woman for a drink of water (Jn 4:7). The woman asked him, “How can a Jew ask a Samaritan woman for a drink?” Jesus answered her, “If you knew the gift of God and who is saying to you, give me a drink, you would have asked, and He would have given you living water” (Jn 4:9-10). The woman responded: “Sir, you do not even have a bucket. Where can you get this living water? Are you greater than Jacob?” Jesus answered: “Everyone who drinks this water will thirst again, but whoever drinks the water I shall give will never thirst again” (Jn 4:13-4).

Jesus is offering the woman both a new heavenly and earthly life. The well symbolized a “thin place.” Today, Christians continue to identify baptismal fountains as sacred or “thin places, where new life is offered.

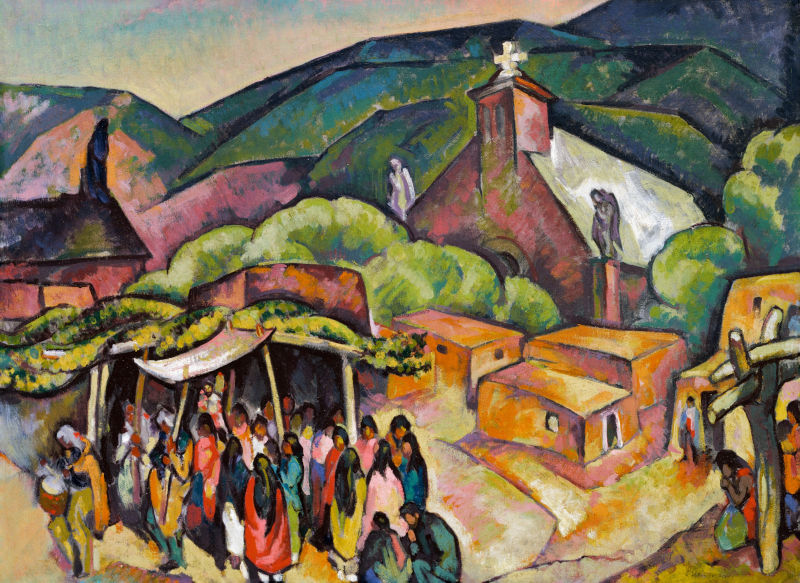

These traditions of “thin places” cross cultures, meaning they are trans-cultural, because of their focus on the land, social identity and roots. These same elements are at the heart of our current social diverse viewpoints. This is especially visible within the Church.

Thin Times: The Post Vatican II Church

Today’s polarization within the Christian Community seems to be rooted in Vatican II. The Council Fathers were aware of two distinct theologies relative to ecclesiology and Christology among its members. The relationship between our modern culture and Christian anthropology seemed to be at the core of these differing theologies.

One group of theologians believed the world was sinful, and the Church served as a sanctuary in the midst of the world. Thus, the world and the Church must remain separate to protect and preserve the Church’s sacredness.

The second group of theologians wanted the Church to redefine its relationship with and in the world. The social movements of the 1960’s may have influenced their understanding of the Church. These theologians argued Jesus sent his disciples to proclaim the kingdom of God and to heal the sick everywhere (Lk 9:1-3). Pope Francis echoed this view in his vision of the Church as a field hospital.

Despite their varying theologies, the Council Fathers defined the Church as the “pilgrim people of God”3 and encouraged its members to go into the world to serve others (LG, 2, §9-13). In 1965, some of the Council theologians initiated a new theological journal based on scripture and salvation history. The goal of Concilium was to educate the Christian community on the theology of Vatican II. Two of the contributors of the journal included Joseph Ratzinger and Karl Rahner.

Around the same time, Jurgen Moltmann introduced the idea of a “Theology of Hope.”4 He taught that God suffers with humanity and promises a better future through hope in the resurrection of Christ and God’s enduring covenantal promise. Moltmann’s idea of a “Theology of Hope” soon became a social movement and embraced by Karl Rahner.

A Biblical Theology of Hope

Hope is what is both desirable and attainable. It is primarily focused on the world to come (Heb 6:11-13). However, Christians hope for both a heavenly and earthly future waiting and working to expand thin places” into the realization of the new time; the new creation (1 Tim 2:1-4). Biblical revelations describe how God provides for our future of hope.

In the ancient biblical record, the Lord blessed the Israelites with prosperity (Gen 12:7), a land of milk and honey (Ex 3:7-9), and a promise never to leave them without hope (Gen 9:8-13). Israel’s hope was centered in God. In the Christian reading of biblical history, this hope is fulfilled by Jesus, the awaited Messiah.5

Jesus announced the arrival of the kingdom, and His mission was to bring healing to a suffering world (Mt 4:17). For example, Jesus healed a blind man on the Sabbath (Jn 9:1-41). He took clay from the ground, mixed it with spittle and placed the mud on the man’s eyes (Jn 9:6-7). Jesus’ healing utilized both a earthly substances (clay, spittle) and a heavenly one (Jesus’ invocation that he is the light of the world). Through the merging of these elements, the blind man was able to see and encounter the divine.

After placing the mud on the man’s eyes, Jesus sent him to wash in the Pool of Siloam (Jn 9:11) which was a historical site that provided life-giving water for the town (2 Kgs 20:20-23). The man washed in the pool and emerged from his encounter in the watery “thin place” a disciple of Jesus.

On the other hand, the Pharisees refused to accept Jesus’ healing powers because he cured on the Sabbath which was against the Mosaic Law.

Echoes in On-Going, Disputed Reception of Humanae Vitae

A similar division surfaced among the Vatican II theologians over Pope Paul VI’s position on artificial and medical contraception articulated in Humanae Vitae (1968).6He argued it was against natural law (HV,2, §11).

Pope John XXIII had commissioned a group to study the issue in 1963, but their findings were not reported until 1966. The commission reported that oral contraception was not intrinsically evil. However, Pope Paul VI’s advisors rejected their findings, saying the end does not justify the means.

Several theologians disagreed with Pope Paul’s conclusion. For example, Charles Curran said the Church Fathers changed their thinking on slavery because it was not an infallible doctrine.7 Therefore, Curran argued, since contraception is not an infallible doctrine, might it also be changed? Jesus’ healing of a blind man on the Sabbath also supports this hypothesis. In fact, the law against healing on the Sabbath changed (Jn 9:15).

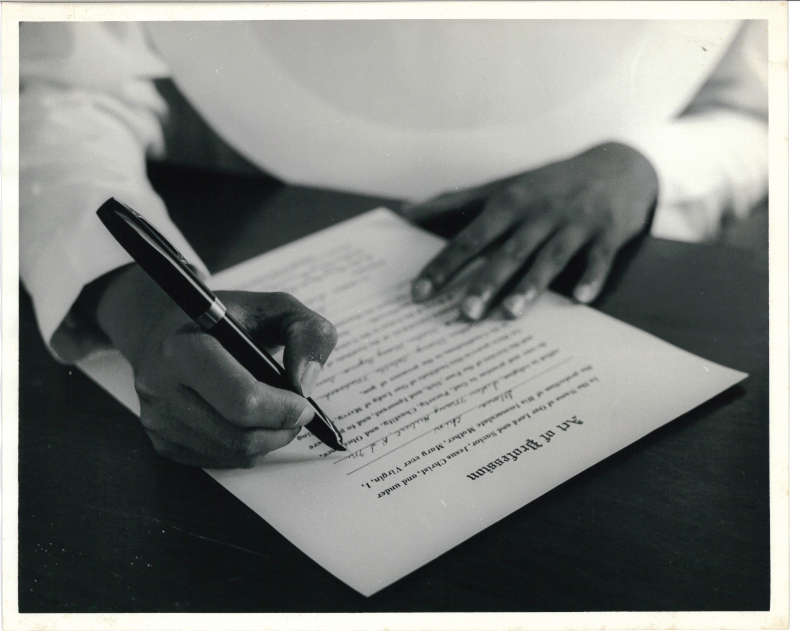

Several theologians signed a letter disagreeing with the implementation of Humanae Vitae. Karl Rahner was among those who signed the letter, while other theologians affirmed Pope Paul’s position. Joseph Ratzinger was among those who accepted Pope Paul’s conclusion. He withdrew from the Concilium theologians, and later established a second journal, Communio, to reinforce the Church’s teachings (1972). Both theological positions continue the tug-of-war amidst contemporary Catholic theologians and the Church magisterium.

From time to time, prophets emerge to encourage the faithful to change their way of thinking. Some Christians consider Pope Francis a contemporary prophet. He is recommending a renewed vision of the Church that is rooted in the early Christian Communities (Jn 20:21) and reflects the spirit of Vatican II (LG, 2, 17). He wants a Church that is open to everyone (Gal 3:28), listens to the needs of the people (Is 54:2) and reflects the spirit of compromise (Gal 3:23-9).

Theologian Richard Rohr affirms Pope Francis’ vision for a new Church. He invites each of us to live on the edges of the Church so that we can listen and respond to the cries of the poor and the needs of a suffering world. In essence, he is calling us to be prophets.8

Both Richard Rohr and Pope Francis are calling for that metanoia that brings us back to God’s vision to tend and steward our common home and all God’s pilgrim people on our human journey through the Church to our eternal Home. Pope Francis’ Synod on Synodality is a first step in achieving together the sacred goal of our lives.

Enlarging Your Tent: A “Thin Place” for a Future Church

Those who participated in the consultation sessions for the 2023-24 Synod seem to concur with Pope Francis’ vision of a future Church. The participants desired a unified Church within a diverse world. The continental working document, “Enlarge the Space of Your Tent,” is a synthesis for the Synod discussions, and reflects both the concerns and hopes to be addressed (ET, 3, §29-103). 9

The synodal journey is like the biblical image of a collective exile (Is 54:2). The concept of a collective exile reflects the prophet Isaiah’s address to the Israelites. He reminded them that God was with them in the dark days of their exile. Their God was also a forgiving and loving deity that would always be with them even in the dark days to come (Is 54:2-8). This is also a message for each of us as we journey through thin times on our way to an unknown future for our Church.

Using the image of a tent, the worldwide Synod participants described their journey (ET, 3, §27). The tent is a new symbol for a thin place which connects our past with the present and unfolds for us a possible future. The tent implies individuals can move in and out freely and when necessary, one can pick-up the tent and relocate somewhere else.

The Christian Community seeks unity by following Jesus’ way of living (ET, 3, §27). They also ask each of us: to recall our baptismal theology of Vatican II (ET, 3, §66), to be open to changes within Canon Law in order to meet the changing needs of God’s people (ET, 3, §71) and to focus our prayer on biblical texts (ET, 3, §95).

In addition, the participants are recommending that our clergy go out to the people they serve. (ET, 3, §99) and emphasize the need for the clergy to seek a solution to the distribution of the sacraments for divorced and remarried Catholics (ET, 3, §93). They also remind us that Christ initiated a covenant that calls Christians to be the new People of God (1 Pt 2:9-10). Therefore, they ask that each of us visit a sacred (thin) place in order to transform our lives (ET,3, §101).

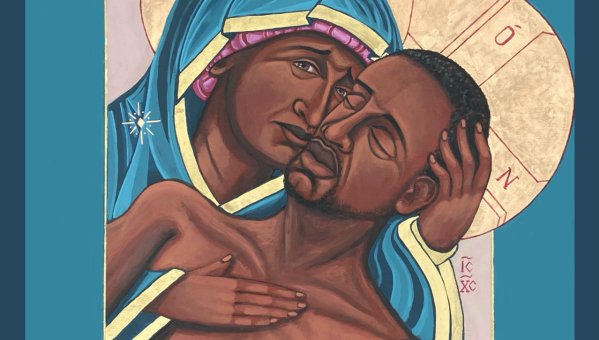

The new People of God are seeking a theology built upon the remnants of the early church and the spirit of Vatican ll. The emerging Christian Community is desiring a Church that is united in its purpose and no longer divides people because of racial or ethnic differences (Gal 3: 27-8). They desire a Church that brings peace by breaking down walls that separate people (Eph 2:14-6).

They want a Church that embodies the spirit of Vatican II and reminds us that Jesus called us to be one people with a new covenant to love everyone (LG, 2, §9). The image of a tent seems to capture the hope for a future Church because no one is excluded.

Conclusion

Our Christian spirituality is built upon a multiplicity of traditions that have contributed to a fragmented, divided Church (ET, 3, §87). Yet, we remain under one tent. Pope Francis warns the Christian community that unless we accept the synodal process and enlarge our tent, the Church will continue to be polarized (ET, 3, §30). The synodal process is: simply walking together, breaking one bread and everyone partaking of the one bread (ET, 4, §103).

Thus, the People of God are inviting each of us into this process. This is our hope for a Church that brings Christ’s peace to a suffering world. Our Church depends on our individual and collective response to this request.

How will you respond? Remember, together we are the hope for the Christian Community and the Church. How will we respond to Pope Francis’ invitation to be the new People of God?

Endnotes

1 Sister Marie McKenna, SLM, Webinar, “Thin Places/Thin Times: Religious Life as Lived Through the Curtain of the Past and What is Yet to Be” (Downing, PA: Saint John Vianney Center, January 12, 2023). See https://relforcon.org/video/free/thin-placesthin-times-religious-life-lived-through-curtain-past-and-what-yet-be. Accessed April 23, 2025.

2 Christine Dorman, “Celtic Spirituality: Thin Places.” See https://www.moonfishwriting.com/post/celtic-spirituality-thin-places (October 18, 2019). Accessed April 1, 2023.

3 Walter M. Abbott, SJ General Editor, The Documents of Vatican II (New York: American Press, 1966). References to the document on the Church (Lumen Gentium) will be indicated by the abbreviation, LG, the chapter and paragraph numbers.

4 Jurgen Moltmann introduced the idea of a Theology of Hope in 1964. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jürgen_Moltmann. Accessed April 1, 2023.

5 Xavier Leon Dufour, Dictionary of Biblical Theology (Seabury Press: New York, 1983), pp. 239-43.

6 Pope Paul VI, Humanae Vitae. Holy See, 1968. See https://www.vatican.va/content/paul-vi/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-vi_enc_25071968_humanae-vitae.html. Accessed August 19, 2007.

7 Charles Curran, “Humanae Vitae and fidelium.” See https://www.ncronline.org/news/humanae-vitae.June

25,2018. Accessed April 1, 2023.

8 Richard Rohr, “Life on the Edge: Understanding the Prophetic Position.” See https://www.huffpost.com/entry/on-the-edge-of-the-inside_b_829253. Accessed April 1, 2023.

9 “Enlarge the Space of Your Tent” (Vatican City, Italy: October 2024). Here abbreviated as “ET.” This was the document produced by a team of 30 advisors,mostly lay persons, who gathered in Frascati, Italy in late September and early October 2022. This provided the framework for the continental phase of the Church’s on-going synod process, which involved gatherings on every continent prior to the first assembly in Rome in October 2023 as well as the one in October 2024.