All across the Institute we are praying to be “Shaped by the Spirit’s Fire – Fonnados por el Fuego del Espiritu.”[1] Though we do not yet see all that God’s fire wishes to create in us, we find ourselves, even when we are alone, singing Dolores Nieratka’s suppliant refrain: “Spirit of all wisdom, Spirit of earth, Kindle the bright vision, Quicken rebirth. Spirit of all wisdom, Spirit of God, Touch our hearts with your fire.”[2]

Somehow we know, beyond all doubt, that the eager enkindler of our personal and corporate vocation as Sisters of Mercy is, even now, steadily at work among our dry bones and sinews. More than anything else in this world we wish to surrender to this enflaming. We realize that we are not the source of the ardent shape we hope to become, only the ready tinder: poor, flickering, utterly dependent on God’s designing fire.

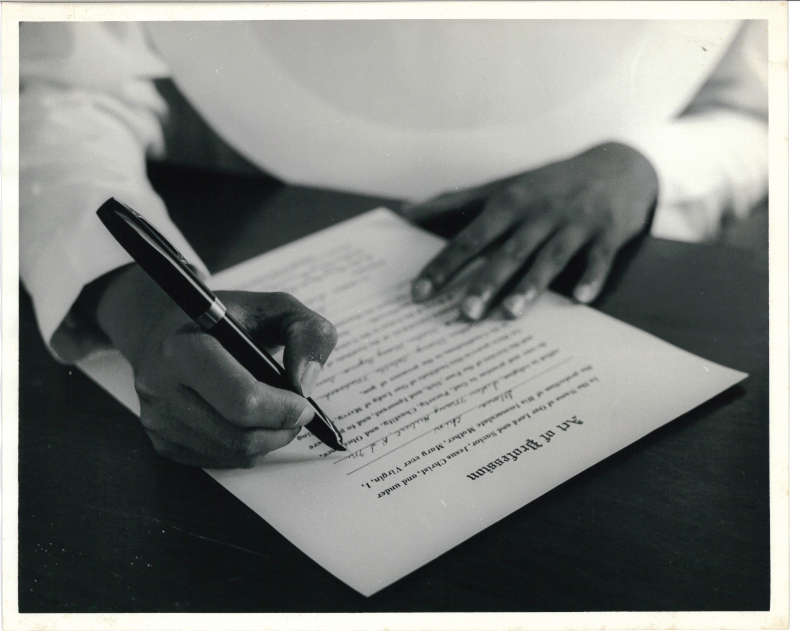

In this moment of discerning the shaping flame within us, we read—perhaps for the hundredth time—our Constitutions and Direction Statement, trying to understand what “conversion” shall really mean for us. We know, beneath all human explanation, that these documents are not simply or primarily our own creation. In these smoldering verbal commitments, crafted four years ago, the flame of God’s diligent reshaping of our “lifestyle and ministries” is daily building energy and seeking our collaboration. In these human words, God’s own enkindling vision is truly given to us as the bright form of our rebirth if we will but yield to it. We realize that the conversion to which we are now insistently called is not just a comfortable restoking of the low but familiar embers. We sense that the regenerating Spirit within us wishes to enkindle a much more critical and thorough blaze.

No one can undergo our personal and corporate conversion for us. No predecessors or supposed successors. But there is one person who unflaggingly accompanies us in our present encounter with the Spirit’s fire and who ardently attends our reshaping: one who loves us and cares deeply that we be rekindled; one who is herself an enduring example of the depth of conversion born of God’s Spirit. We have said, perhaps without fully understanding our own words, that we wish to be “animated” by her “passion for the poor” and by the gospel which so radically enflamed her life. She now urges us to conform our lives and ministries to the full reality of these words; and, for our encouragement, she humbly offers us the memory of her own passionate loving, hoping, and daring.

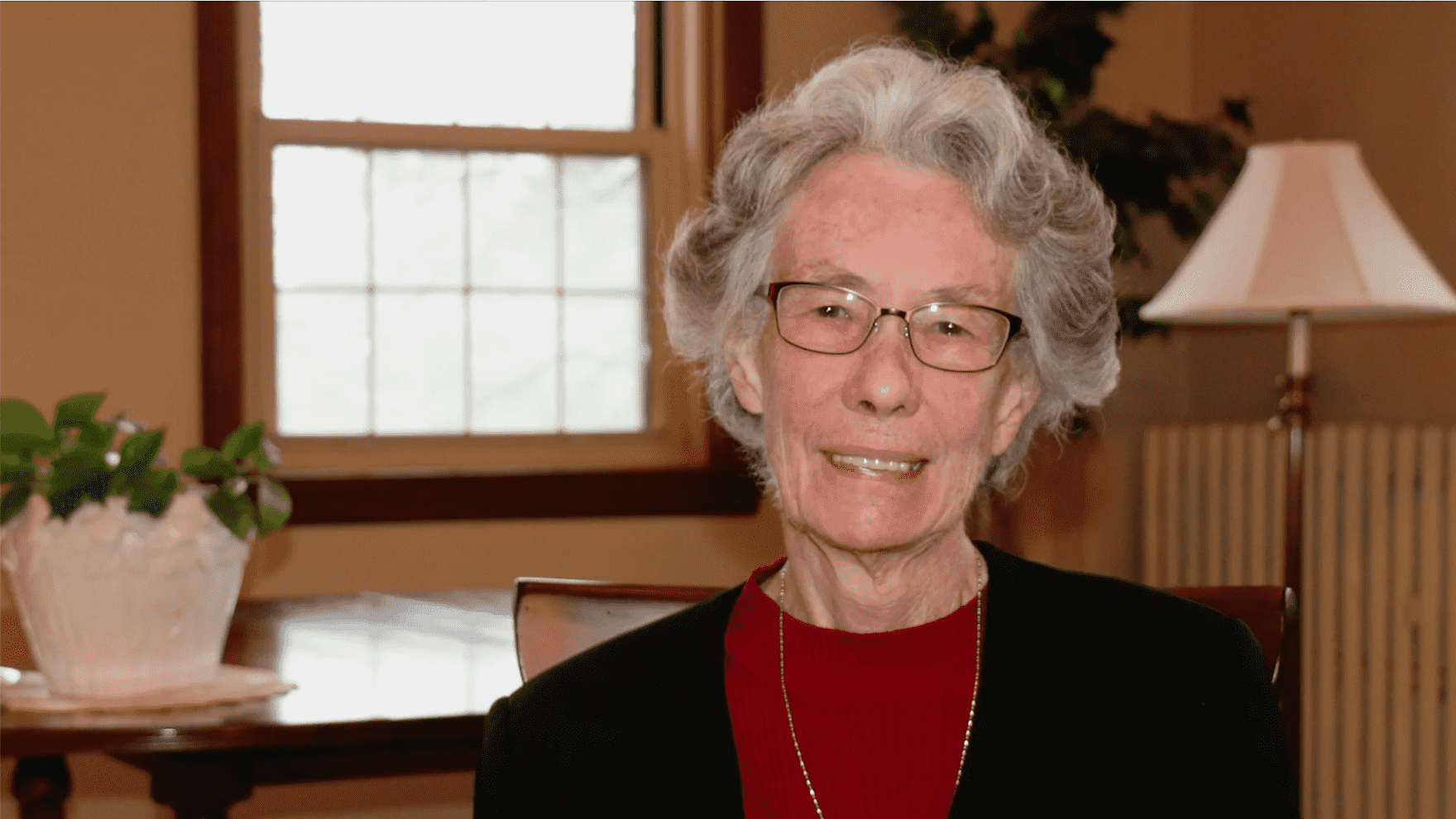

Catherine’s Loving

When we talk about Catherine McAuley’s passion – her passion for mercy, her passion for the poor, her passion for the life and work of the Sisters of Mercy – we are, I think, talking about the most profound belief that animated her whole being and all she did: her burning belief in the unity of the love of God and the love of our neighbor.

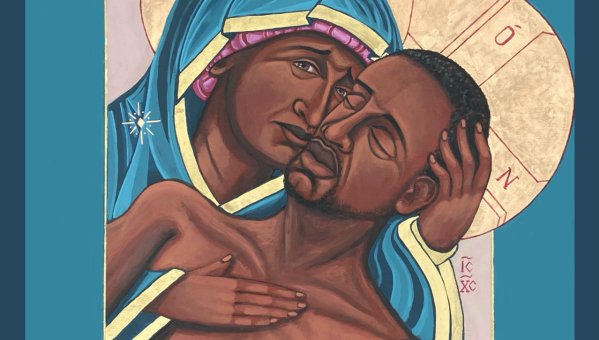

She had a completely whole-hearted love of God and ardent love of Jesus Christ and of all that Jesus is for us and has done for us. She had a fervent belief that Christ really is present and beckoning, with love and for love, in the faces and lives of the poor, the sick, the homeless, the untrained and uneducated and unconsoled, the dying and the despairing. She believed that Sisters of Mercy, and those who wish to be associated with us, are called to find this great love of God, and to bring this great love and consolation of God in and to all those who suffer. All this ardor flowed vibrantly from Catherine’s deep-felt, consuming belief that Jesus the Christ really is identified with all human beings, and that we can ardently love the God whom we do not see only by ardently loving the sisters and brothers whom we do see.

The gospel text on the reign of God in Matthew 25 to which she refers twice in her Rule, was not a distant, unattainable ideal, but Jesus’ daily, hourly beckoning, to her and to us. “Come, you that are blessed by my Father … for I was hungry and you gave me food; I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me….Truly I tell you just as you did it to one of the least of these who are mine, you did it to me” (Matthew 25:34-36,40).

Catherine truly believed this word of Jesus. She was, therefore, earnest, zealous, whole-hearted in her daily desire to love her neighbor. She was not measured, cautious, self-protective, gingerly, in the donation of herself in love. At the heart of her belief in her vocation as a Sister of Mercy was her desire to resemble Jesus, and she realized that, like him, she must sacrifice herself for the sake of such loving. She was, therefore, completely willing to forego her own plea sure and ease, to put aside her own needs and preferences, to give up what would have comforted her, to displace herself, to bestow herself, to let herself be radically shaped by the Spirit’s fire for the sake of the love and presence of Christ in those in need. She really believed and lived the greatest commandment: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength [and] you shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Mark 12:30-31).

When one talks about love, it is all too easy to sound vague and lofty. What I am trying to say is that Catherine really took to heart Jesus’ claim: “Whatever you do to the least of these who are mine you do to me.” She got out of bed at 5:30 each morning, impelled by this belief. She spent every day for seven months in a cholera hospital, penetrated by this belief. She welcomed homeless women and children, seized by this belief. She knelt by the bed of her young, dying companions, overcome by this belief. She started schools for neglected girls, urged on by this belief. She took long, fatiguing journeys, consumed by this belief. She walked the streets of Dublin, Kingstown, Limerick, Galway, and Birr, in all kinds of weather, devoured by this belief. She reverently entered the dwelling places of the sick and poor, filled with this belief. When she said: “God knows I would rather be cold and hungry than the poor in Kingstown or elsewhere should be deprived of any consolation in our power to afford”[3] she meant it, and she was often cold and hungry for their sakes.

It was Catherine’s belief that our vocation as Sisters of Mercy is a call to give everything we are and have for the sake of God’s dear poor. Therefore, she did not hold back, she did not consult her own interests, she did not ration her presence to those in need, she did not conserve money or energy for a rainy day, she did not retire from loving. She often gave up her own bed, she was the last to eat at meals, she chose the cheapest means of transportation, she often slept on the floor in new foundations rather than delay the work of mercy until these convents were completed, and her underwear was, according to her companions, of the “meanest description” – she who had once dressed in high style and driven a handsome Swiss carriage. As one of her early companions said, “Every talent and every penny that our dear foundress possessed had been devoted to the poor” (Clare Augustine Moore, Memoir).[4] And a woman who placed an abandoned child in the House of Mercy once said of her, “She made me feel what real charity and real religion is.”[5]

Catherine believed that to be a Sister of Mercy is a sacrifice of one’s self for the sake of the reign of God—a sacrifice enkindled by Jesus’ own self-donation, a sacrifice promised at one’s profession of vows, but consummated only in a life-long willingness to pour one’s self out, in the daily self-bestowal, the steady libation, that these vows imply and should evoke. She found this a joyous way to expend her life. On the very day she died, she said to Mary Vincent Whitty, a young professed sister at Baggot Street, “If you give yourself entirely to God—all you have to serve him—every power of your mind and heart—you will have a consolation you will not know where it comes from” (Letter to Mary Cecilia Marmion, November 12, 1841).[6]

Catherine believed that she and we often fail to sustain the completeness of the gift we once intended: we forget that we have completely handed ourselves over for the sake of God’s loving purposes, we start squirreling away little nuggets of our life, we miss the “fine print” on the vows we have professed. But she also believed that the daily renewer and enflamer of this gift of ourselves is God’s own faithful Spirit, and that we are never too old to learn to be more fully what we say we are.

Clare Moore says that Catherine’s desire to “resemble” Jesus in his own merciful loving was “her daily resolution, and the lesson she constantly repeated.” She used to say to the first sisters: “Be always striving to make yourselves like Him—you should try to resemble him in some one thing at least, so that any person who sees you, or speaks with you, may be reminded of His blessed life on earth” (Bermondsey Annals).[7] She treasured the gospel acts and words of Jesus, and often said to her first companions, “If His blessed words ought to be reverenced by all, with what loving devotion ought the religious impress them on her memory and try to reduce them to practice” (Bermondsey Annals).[8] She wished us to be such a transparent community of love, such a fire of ardent love for others, that people would really see each one of us as the loving Christ, even as we reach out to the loving Christ in them.

Catherine was herself the best example of what she meant. The generous zeal of her own charity, the unquenchable flame of her own loving, was indeed fervent and unwearied, even when she was—as she sometimes admitted—tired, nervous, sick, perplexed, or oppressed with care. At the dedication of the Baggot Street chapel in June 1829, when she, at fifty-one, was just beginning the work of love of her final years, her good friend, Michael Blake, preached the sermon and said of her, “I look on Miss McAuley as one… specially endowed with benediction: her heart is overflowing with the charity of the Redeemer whose all-consuming fire bums within her” (The Limerick Manuscript).[9] Catherine believed deeply in this enabling Fire of God’s love. She was willing to be impelled by it every morning, and to be consumed by it every day.

On a blank sheet in the front of her copy of A Journal of Meditations for Every Day of the Year, Catherine wrote this prayer, which she prayed each morning for the Baggot Street community: “Come Holy Ghost, take possession of our hearts and kindle in them the fire of thy divine love shed upon us we beseech thee the plentitude of thy divine Spirit and give us an entire and perfect submission to the inspiration of thy Grace….” This simple prayer, with all the generous love and self-donation it asks for and promises, is the heart of what she believed, for herself and for us. She prays it for us now—as we contemplate the Spirit’s shaping Fire and try to understand what it really means to say, “God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given us” (Romans 5:5).

Catherine’s Hoping

Catherine conceived of her life and of the life of our community as a pilgrimage, a journey, a going for ward in hope, “relying with unhesitating confidence on the Providence of God” (Neumann, ed. 353).[10] Less than two months before she died, she told Mary Ann Doyle: “We have ever confided largely in Divine Providence and shall continue to do so” (Neumann, ed. 376).[11] But she was not passive in this journey. As she wrote to Frances Warde: “while we place all our confidence in God, we must act as if all depended on our exertion” (Neumann, ed. 256).[12] Thus a trusting, energetic movement forward, in the strength of God’s efficacious presence, characterized her whole life.

When she lived with the Callaghans, she hoped that one day she might be able to rent a few rooms in which to shelter young girls who were endangered on the streets of Dublin. When she received the Callaghan inheritance and began to build the large house on Baggot Street, she feared the magnitude of what she had undertaken and hoped God would help her carry it through. When Edward Armstrong, her strongest supporter, died in May 1828, she hoped she would have the courage to follow his repeated advice to her, “Place all your confidence not in any human being but in God alone.”

When clergy and laity harshly criticized the community on Baggot Street, and called her an upstart and a parvenu, and she feared that the works of mercy they had begun would come to an end, she hoped God would lead her through this controversy. When she and her companions decided to found a new religious congregation and three of them went to George’s Hill, she hoped the community on Baggot Street would survive in her absence. When the Presentation Sisters intimated that they might not let her profess her vows if she did not remain in their order, she hoped in God’s mysterious help.

When Caroline Murphy died while Catherine was at George’s Hill, and then Anne O’Grady, Elizabeth Harley, and her own niece Mary Teresa died in the first two years, she hoped death would not destroy the young community. When foundations went to Tullamore, Carlow, and Cork with too little money to live on, and to Charleville with no prospect of postulants, and to Birr with no assured income, she hoped God would provide for them. When she appointed young women as the superiors of the new foundations—Mary Ann Doyle was 25, Frances Warde was 27, Clare Moore was 23, Juliana Hardman was 28—she deferred to their authority and trusted that God would direct them. When the ministry of each new foundation turned out to be different from that of the last, and different from the one on Baggot Street, she trusted in the mercifulness of these women and in God’s unfailing guidance. At the very end Catherine expressed only one hope for the Sisters of Mercy: that they would live in union and charity and rely on God’s merciful help. If they did this, all the rest would follow.

Catherine’s hoping was not an easy wishing for her own personal well-being or fulfillment, nor an ahistorical invocation of the resurrection of Christ, but a “hoping against hope” (Romans 4:18) in the face of widespread human affliction. Hers was a tenacious, active hoping at the service of the God-desired wellbeing of the poor, the sick, the dying, the neglected, and the unjustly treated. It was the kind of dogged hoping that is urgently aroused by human suffering and leads to the Godly fatigue of the cross of Jesus, where all genuine prayer for God’s action begins.

No story of Catherine’s life so tenderly illustrates her hoping as does her exhausting service in the make shift cholera hospital. As Clare Augustine Moore explains:

The first cholera broke out in Ireland in 1832, and the people were most injuriously prepared for it by the terrible accounts of its virulence in other countries. It certainly was an awful visitation. The deaths were so many, so sudden, and so mysterious that the ignorant poor fancied the doctors poisoned the patients, and as immediate burial was necessary it was reported that many were buried alive …. It was under these circumstances that Revd. Mother offered her services to the cholera hospital, Townsend Street…. The Archbishop having approved of this step the sisters entered on their duties to the great comfort of the patients and doctors; but the fatigue they underwent was terrible. Revd. Mother described to some of us the sisters returning at past 9, loosening their cinctures on the stairs and stopping, overcome with sleep.[13]

Catherine herself remained at the hospital most of the day—nursing those whose lives could be saved, comforting the dying, preventing mistaken burials, and supervising the volunteer nurses. The image of her collapsed body on the Baggot Street spiral stairs is a vivid emblem of the extent of her self-giving, and of the kind of to-the-last-ditch hoping she and the Spirit’s fire shall wish to see in us at the end of the day.

Catherine’s Daring

Catherine had an extraordinarily humble opinion of herself and of her role as the founder of the Sisters of Mercy—a title she never used of herself. She was lowly in her own eyes, and she often attributed the sufferings and trials of the community to her own mistakes and failures, to such an extent that Clare Moore says of her: “I used to grieve to hear her condemning and blaming herself so much” (Letter to Clare Augustine Moore, September 1, 1844).[14] Whatever may have been the external causes of Catherine’s estimate of herself-one can easily imagine some of these and regret them-her humility was conceived and rooted elsewhere, in her earnest reflection on the life of Jesus, on his humble presence among those he served, and on the humiliations of his passion and death which are said to have moved her to tears.

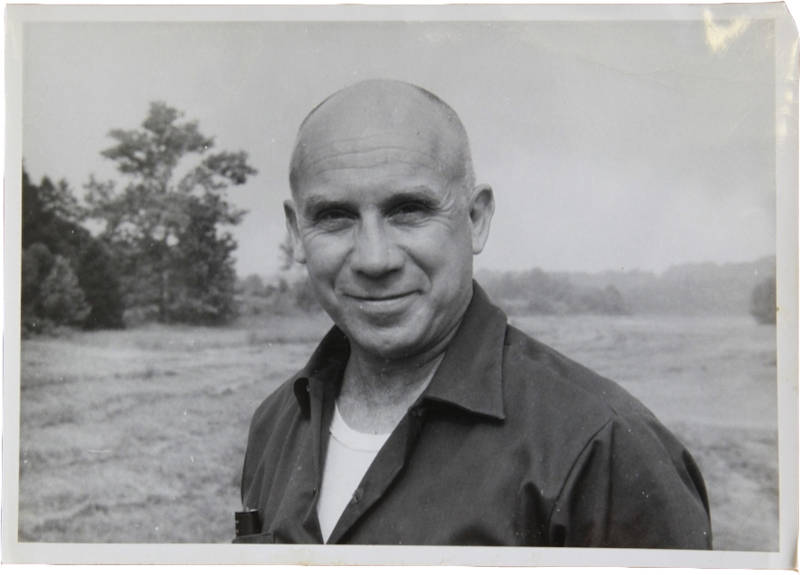

Her truthfulness before the mystery of God’s unfathomable modesty in Jesus was evidently a profoundly peaceful affliction within the privacy of her own heart, but it did not render her publicly timid. On the contrary, her humility seems to have been the condition of the possibility of her God-given daring as an advocate for the poor, and of her unabashed promotion of the Sisters of Mercy for the sake of the poor. She had in these matters the apostolic virtue of boldness—what scripture calls parresia, the publicly venturesome courage to speak and to act on behalf of the bold mission of God in Christ Jesus.[15]

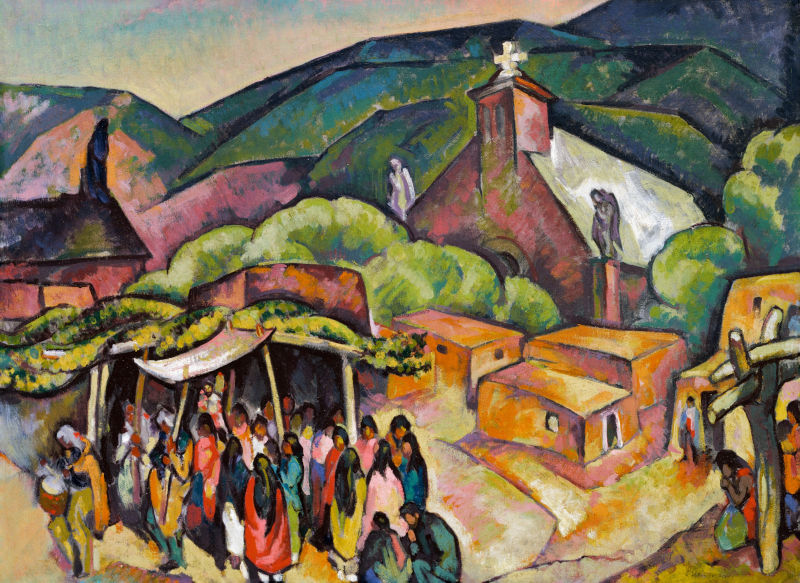

Catherine was passionately convinced that religious life in the Institute of the Sisters of Mercy was nothing less than a gift of God given to the church and the world for the uplifting redemption of all God’s beloved people, especially the most neglected and oppressed. For her the flourishing of the Institute was precisely for the sake of the flourishing of God’s ardent mission among the poor of this world. Therefore she did not hide the community behind closed doors, as the private, personal treasure of its first few members. She boldly wished the Institute to grow, in numbers and in geographical extension, so that the reign of God’s redeeming love—”the fire Christ cast on the earth,” as she called it—might be more and more enhanced.

Our place and time are not Ireland and the 1830s. But, still, what Catherine did to nurture the continued growth of the Sisters of Mercy may inspire us as we seek to refound our way of life and to invite many other women to join us in vowed commitment to the ongoing mission of God’s mercy. We have said we wish to be “shaped by the Spirit’s fire.” A crucial aspect of our long-term shaping will be the healing of our silence and timidity about ourselves, and the rebirth of our apostolic boldness in proclaiming why we are what we arc, and in encouraging others to join us—until the liberating mission of Christ among the outcast and scorned of this world has been completed.

Catherine always sought bold but natural ways of reaching out and allowing the life and work of the Sisters of Mercy to be better known by families and priests, and especially by women who might consider joining the community. For example, the evening prayer of the early Baggot Street community was open to the people of the neighborhood, and women and girls who lived nearby joined in this prayer. Apparently only one chair was stolen! The chapel on Baggot Street was open to the public, and many people came there for Sunday eucharist (until 1834 when the parish priest closed the chapel to the public). Except for the first reception ceremony at Baggot Street in January 1832, all reception and profession ceremonies were open to the public. In the foundations outside of Dublin these nearly always took place in the parish church and were preceded by a procession to the church.

Catherine and the other sisters maintained good contact with priests and spiritual directors and made known to them the life and work of the Sisters of Mercy so that they would be well informed when they counseled women. She involved lay women in the ministries of Baggot Street and the new foundations and welcomed associates and volunteers. She wrote letters to prospective candidates, explaining the religious life of the community and inviting them to come and see.

She arranged an annual public Charity Sermon in which the preacher described the life and purpose of the Sisters of Mercy and solicited personal as well as financial participation in that life. In Dublin, after the first year, these sermons were held in the parish church. Similar sermons were held in the parish churches of the other foundations. She also arranged that within the first month of each new foundation a reception or profession ceremony was held in the town and the public invited. Whenever she could, and some times the respective bishops would not permit this, she accepted poor women into the community, with little or no dowry.

Despite all the painful feelings engendered in the Irish by the British government during the penal era, and despite anti-nunnery attitudes, she founded two convents in England—in London and Birmingham. The house in Bermondsey was the first new Catholic convent founded in London since the Reformation. She always expected that each new foundation would be completed and carried on by new members entering from that locality, and she prayed the Thirty Days Prayer in each new place for this gift of God. She urged that the annual renewal of vows in each community outside of Dublin be made in the parish church, and she led this renewal herself in Birr on January 1, 1841.

In countless public ways, Catherine sought to reach out to women who might become members of the community, and to encourage them to join the Sisters of Mercy. She believed that Christ was indeed casting the fire of this sort of merciful love and hope on the earth, and that it was her constant obligation to nurture it and help it kindle—by making the hopeful, loving, and joyous purpose of the community more widely known.

Catherine’s Shoes

Very early in the morning on the day she died, Catherine asked Teresa Carton for some brown paper and twine; she then tied up her homemade shoes and asked that the bundle be put in the kitchen fire and the coals stirred until its contents were consumed. She who had walked and walked for the sake of those in need now surrendered her worn shoes to God, and to us. Like Moses before the burning bush, and Joshua before the messenger of God, she entered her final historical encounter with the merciful God whom she had so loved and trusted-barefoot.

Her shoes have now, in a true sense, been passed on to us—that we may walk the streets she walked, with the same mercifulness, hopefulness, and joyfulness; that we may find and bring the same consolation of God in and to all those in desperate need; and that following her footsteps we may boldly proclaim the saving mission of Christ and our own God-given attachment to the flourishing of this sacred work.

The Spirit’s fire by which we, like Catherine, yearn to be reshaped is not to be found in a remote, abstract place. It is, even now, blazing in the ordinary, workaday kitchens of our minds and hearts where all true conversion begins.

Notes

[1] Chapter Steering Committee, Letter to Sisters and Associates of the Institute of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas, July 20, 1994.

[2] Dolores Nieratka, RSM, “Spirit.” This gathering song was sung during the Regional Community Reflection Process, September – October 1994.

[3] Letter to Sister M. Teresa White, in The Letters of Catherine McAuley, ed. by Sister Mary Ignatia Neumann, RSM (Baltimore: Helicon, 1969) 142.

[4] Clare Augustine Moore, A Memoir of the Foundress of the Sisters of Mercy in Ireland [The Dublin Manuscript]

[5] The complete texts of all the archival manuscripts quoted in this reflection are presented in my book, Catherine McAuley: The Tradition of Mercy (Blackrock, Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1995).

[6] Letter to Mary Cecilia Marmion, November 12, 1841.

[7] Bermondsey Annals.

[8] Ibid.

[9] The Limerick Manuscript.

[10] Letter to Sister M. Ann Doyle in Neumann, ed., Letters, 353.

[11] Letter to Sister M. Ann Doyle in Neumann, ed., Letters, 376.

[12] Letter to Sister M. Frances Warde in Neumann, ed., Letters, 256.

[13] Clare Augustine Moore, Memoir.

[14] Letter to Clare Augustine Moore, September 1, 1844.

[15] See Karl Rahner’s essay, “Parresia (Boldness),” in Theological Investigations 7 (London: Darton, Longman, and Todd, 1971) 260-67.

This article was originally printed in English in The MAST Journal Volume 5 Number 2 (1993).