The word “prophetic” is often used in relation to religious life: as an exhortation, a complaint, a compliment, an assurance, a definition, a description. In fact, it is currently quite a fashionable word: if one can say that someone or something is “prophetic,” one’s theological vocabulary, at least, is not outmoded. I myself have used this word in the past as if it made no demands on my life, and as if something could be made “prophetic” simply by declaring that it was “prophetic.” But today I am conscious of the superficiality of such talk, and of our need to explore more deeply the precise and thorough nature of the prophetic vocation.

I hope to show that the life and work of Catherine McAuley and the first Sisters of Mercy was indeed prophetic, in the truest biblical sense. But as I do so, I am aware that I will be holding up a contrasting mirror to my own life and work, and I may also be holding up a contrasting mirror to your life and work.

The Silver Ring

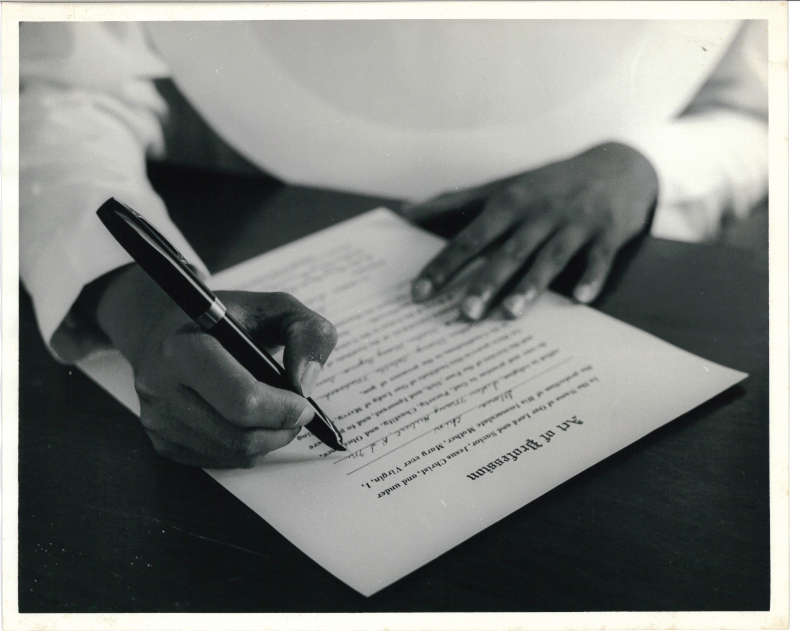

I would like to situate our reflections around the very plain but enduring symbol of Catherine’s silver ring, the plain silver band which she received at her profession of vows and which every Sister of Mercy since that day, and every Sister of Mercy in this room, has received. This ring is not a piece of ornamental jewelry, perhaps one among many; and it is not simply a convenient tag or code-object, worn toward off potential suitors on subways or in supermarkets! This silver ring, if it is what it is meant to be, is a visible sign of the call to prophecy, a call received, accepted, and lived.

In the ceremonial for profession of vows that was used by the first Sisters of Mercy, and was printed in the ceremonial booklet Catherine adapted from that used by the Presentation Sisters, the bishop blesses the ring by sprinkling it with holy water and incensing it, but the words of blessing are not a liturgical formula of blessing, but a proclamation of the Gospel of Matthew. The Gospel text reads in part:

Then Jesus said to his disciples, “If any want to be my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it. For what will it profit them if they gain the whole world but forfeit their life? Or what will they give in return for their life?

In Catherine’s day, when the bishop, later in the ceremony, put the blessed ring on the third finger of the left hand of the newly professed sister, he said:

May Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, who has now espoused you, protect you from all danger. Receive then the ring of faith, the seal of the Holy Spirit, that you may be called the Spouse of Christ, and if you are faithful, be crowned with him forever. In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.

In Catherine’s day, the professed sister then stood and said aloud, in Latin:

I am espoused to Him whom the angels serve, and at whose beauty the Sun and Moon stand in wonder.

After a further prayer of blessing, the newly professed sister then said aloud, still standing:

Regnum mundi, et omnem ornatum saeculi, contempsi,propter amorem Domini nostril Jesu Christi, quem vidi, quem amavi, in quem credidi, quem dilexi.

[The kingdom of the world, and all the ornaments of the earth, I have set aside for love of our Lord Jesus Christ, whom I have seen, whom I have loved, in whom I have believed, and toward whom I incline.]

We may once have interpreted the “spousal” language in this ritual in too anthropomorphic a way, or worse, in too individualistic a way. We may now think that we have grown or should grow beyond such language and such interpretation. We may therefore be satisfied with the brief statement in our Constitutions:

In keeping with our Mercy tradition, we wear a silver ring, as a sign of consecration. (Constitutions 32)

But I would like to suggest that it is time for us to focus more intently on the meaning of the silver ring of our profession.

This silver ring, which is all we have retained of the visible attire of the first Sisters of Mercy, is not only a most important symbol of Catherine McAuley’s prophetic life and work, and that of the first Sisters of Mercy. For if we wear it truthfully, and if we accept the call and response it signifies, this ring can also be the most tangible daily symbol of our own corporate prophetic identity.

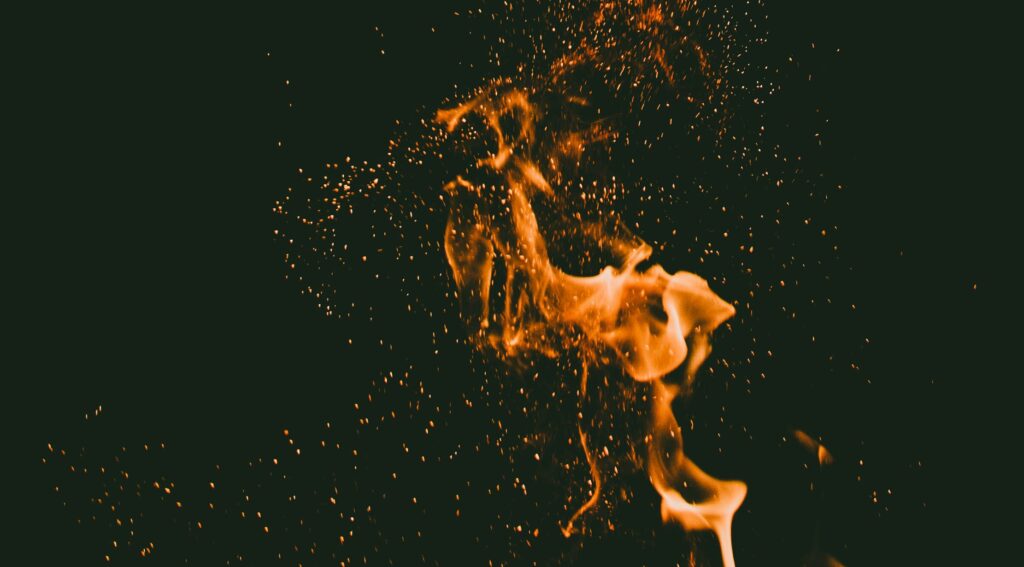

For the ring is intended to be a statement about an experience of God and about the consuming commitment that flows from that experience. Therefore, this ring has more in common with the “live coal” that touched Isaiah’s mouth (Isaiah 6:6), and with the hand that touched Jeremiah’s mouth (Jeremiah 1:9), and with the scroll Ezekiel was asked to eat (Ezekiel 3:1), than we have perhaps realized. The silver ring is a personal and communal identification; it is a mutual pledge between the wearer and the God to whom she put out her hand and to whose word she opened her mouth.

The empowering obligation of this ring is like Isaiah’s saying: “Here I am; send me!” (Isaiah 6:8); it is like the “burning fire” within Jeremiah (Jeremiah 20:9); it is like Deborah’s challenging Barak to assemble forces to liberate the Israelites from the Canaanites (Judges 4:8-9); it is like the aged Anna’s speaking “about the child to all who were looking for the redemption of Jerusalem” (Luke 2:37-38). This ring is meant to declare—in a simple but visible way—the wearer’s public acceptance of a public responsibility to speak for God.

The Call to Prophecy

The biblical call to prophecy is not an invitation to say what is on one’s own mind. It is a call to a much more disciplined and self-effacing speech act. It is a call to submit to the purification of one’s mind and heart and lips so that one may receive from God the word to be uttered. And then it is a humbling, consuming call to go where one is sent, and there to speak for God—to utter aloud, before all the people, in speech and in action, the word of and from God.

This speaking of, from, and for God is the very purpose of the profession of religious vows: this is the call and the response signified in the silver ring of the Sisters of Mercy. And this is the biblical explanation of the prophetic life and work of Catherine McAuley and the first Sisters of Mercy: their surrender to the purification of their lips, and their proclamation of God’s word.

I would like to dwell on these two intimately related aspects of the life and work of Catherine and the first Sisters of Mercy: 1) their constant and ever more deeply purifying realization that it was God’s word and God’s mercy and God’s love and God’s revelation that had seized their lives; and then 2) their consuming willingness to utter that word, that mercy, that God-love, publicly, in speech and in action, such that their public identity was precisely as speakers of, from, and for God’s values and God’s presence.

First, let us talk about their purifying, seizing experience of receiving the word of God into their lives.

It is so easy to walk around as Sisters of Mercy unseized by the call of God: preoccupied by the distracting or comfortable calls of the “world,” very busy dressing our professional sycamore trees (Amos 7:14), not wanting to become a “laughingstock” (Jeremiah 20:7), taking cover in our alleged youth or age or inability to be eloquent (Jeremiah 1:7). It is so easy to lead a life, even as a Sister of Mercy, that does not make itself available to the live coal of God’s call to prophecy. It is so easy to hunker down before God’s revelation and not open our mouths to the transforming touch of God’s word.

Catherine McAuley and the first Sisters of Mercy were not like this. Their whole conception of prayer and of spiritual reading was to make themselves deliberately available to the call of God; to place themselves docilely before the revealing, transforming presence of God’s Spirit; to let themselves be touched by and purified by God’s word; to open themselves to the ever more fiery and demanding realization that they were called to be not just a nice group of women who did helpful things for other people, but rather a religious community who were seized by the presence and word of God.

Let me recall for you the scenes and sayings you know so well:

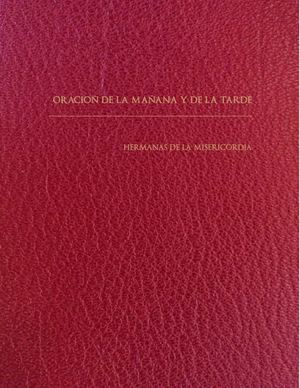

- from the very beginning, the community on Baggot Street prayed together several times a day, but always in the early morning and before they went to bed;

- at least in the beginning, Catherine herself rose earlier than the rest, so that she might pray alone, or with a few others, the Psalter of Jesus, a prayer which by its repetition of Jesus’ name and by its content helped her to remain centered in the realization that it was God’s work, not her own, in which she was engaged;

- the whole consciousness of the Baggot Street community was a readiness to hear God speak to them—an awareness that God had spoken to them and was, even now, speaking to them;

- there was in Catherine and in the first sisters a deep desire to be recollected, to be mindful, that they were acting from, for, and because of the action of God;

- in the Rule she composed, Catherine said of the “Visitation of the Sick”: the sisters shall pass through the streets “preserving recollection of mind and going forward as if they expected to meet their Divine Redeemer in each poor habitation” (Rule 3.6, in Sullivan, ed. 298);

- the community meditated every day on the scriptures, especially on the life and ministry of Jesus: they used Catherine’s Journal of Meditations for Every Day in the Year, a highly respected volume of scripturally-based daily meditations originally composed in Latin in the seventeenth century;

- Catherine and the first Sisters of Mercy read from the lives of the saints every day; and in the lives of the saints they experienced the call of God in the inspiring example of other Christian lives;

- Catherine repeatedly urged the first Sisters of Mercy to contemplate the example of Jesus Christ and to seek to bear “some resemblance to Him, copying some of the lessons he has given us during His mortal life, particularly those of His passion” (Neumann, ed. 330);

- Catherine was so convinced that the physical presence of a Sister of Mercy should be, for others, a presence of God, that Mary Vincent Harnett says:

her desire to resemble our Blessed Lord… was her daily resolution, and the lesson she constantly repeated. “Be always striving,” she would say, “to make yourselves like your Heavenly Spouse; you should try to resemble Him in some one thing at least, so that any person who sees you may be reminded of His holy life on earth.” (Limerick Manuscript, in Sullivan, ed. 181)

- Catherine and the first Sisters of Mercy embraced silence, not in an oppressive way, but as, as she said, “the faithful guardian of interior recollection,” as a help to interior reflection on who one was before God and what one was about on God’s behalf (Rule 8.1, in Sullivan, ed. 303);

- they treasured what they called “mental prayer,” as a means that God would use “to imprint deeply on the mind the sublime truths of religion, to elevate the soul, and enflame the heart with the love of God and of Heavenly things” (Rule 11.2, in Sullivan, ed. 306);

- they suffered in their own personal and communal lives—in countless, constant ways: poverty, hunger, illness, heavy work, numerous deaths—but they consciously chose to receive that suffering as the Cross of Christ, to let the continuing redemptive work of the suffering and death of Jesus Christ enter their own lives as the revealing call of God;

- and in 1841 Catherine herself said of her Lenten reflections:

The impression made on our minds by forty days meditation on Christ’s humiliations, meekness, and unwearied perseverance will help us on every difficult occasion, and we will endeavour to make Him the only return He demands of us, by giving Him our whole heart, fashioned on His own model—pure, meek, merciful and humble. (Neumann, ed. 333-34)

What I am trying to say, by accumulated references to the earliest documentary sources, is that Catherine McAuley and our first sisters in Mercy conceived of themselves and defined themselves as women addressed by the voice of God, and they allowed themselves to be so addressed. They did not use the word “prophetic” to describe the purifying call they felt in their lives, but that is the biblical name for what they allowed themselves to experience and for what Jeremiah experienced:

Then I said: “Ah, Lord God! Truly I do not know how to speak, for I am only a boy [or a nineteen-year-old girl, or a fifty-two-year-old woman].” But the Lord said to me, “Do not say ‘I am only [this or that]’ … for you shall go to all to whom I send you, and you shall speak whatever I command you … ” Then the Lord put out his hand and touched my mouth; and the Lord said to me, “Now I have put my words in your mouth. See, today I appoint you over nations and over kingdoms … stand up and tell them everything that I command you.” (Jeremiah 1:6-10,17)

The Prophetic Mission

To speak as a prophet is, as the Hebrew prophets understood and as Jesus himself demonstrated, to speak of, for, and from God. It is to declare, in one’s human words or deeds, the will and revelation of God. To speak of, for, and from God does not require that one use the word “God” every time one opens one’s mouth, but it does require that one’s words and actions witness to God’s revelation, that they announce God’s true character, attitude, relationship, and action with respect to human life.

If we study the life and work of Catherine McAuley and the first Sisters of Mercy we cannot fail to be struck by the “of God” character of their utterance—I mean, the utterance of their whole lives, the public expression of God which their lives declared, whether in words or in deeds. But before we look at their lives in detail there is one other characteristic of true prophets that we see in Catherine and the first sisters: absolute dependence on the help and virtue of God.

The true prophetic mission appears and is overwhelming. To accomplish what God asks, to go where one is sent, and to speak what one is asked to speak, is always beyond the prophet’s own personal capacities and virtues; the true prophet always knows that he or she is in radical need of God’s help and presence, if his or her prophetic utterance is to be truly “of God.”

So the most prominent prophetic qualification of Catherine McAuley was her profound humility and purity of heart (Clare Moore even spoke of Catherine’s “self-contempt” [Sullivan, ed. 93]), but the first Sisters of Mercy also grew into such humility and purity. Certainly they were willing to open their minds and hearts and lives to the live coal of God’s call to live and speak prophetically—to be publicly seen as women of, for, and from God. And the early history of the Sisters of Mercy in Ireland and England is filled with their prophetic deeds and utterances.

Yet Catherine McAuley and these very ordinary women, who had initially no special genius of their own, were from the beginning conscious of their youth, their lack of know-how, their timidity, their lack of public skills, their inexperience before the world and before the Gospel, their lack of any sort of personal authority, and the fragility and sickness of their community. Added to all these weaknesses were the social and ecclesiastical incapacities attributed to their gender. Naive as the first Baggot Street community were about some things, they were not unaware that their parish priest “had [as Clare Augustine Moore recognized] no great idea that the unlearned sex could do anything but mischief by trying to assist the clergy” (Dublin Manuscript, in Sullivan, ed. 208).

We see in all these deeds and utterances some of the classic forms of prophetic speech on behalf of God: the promise, the reproach, the admonition, and occasionally the threat. For example:

- Catherine’s own decision to give up her entire inheritance and all her future personal security to build a House of Mercy for poor women and children because Jesus had said: “Whatever you do to the least of these who are mine you do to me” (Matthew 25:40);

- her declaring God’s regard for the precious human life and the blessed eternal life of those dying of cholera by the way she cared for them, knelt by their cots, prayed with them, protected them from premature burial, and consoled them with assurances of God’s love;

- her defense of the sacra mental needs and rights of the servant girls and women in the House of Mercy, against the inadequate arrangements conceded by Rev. Walter Meyler, the parish priest and a close friend of the archbishop; and her offering to him, in vain, a greater annual salary for these sacramental services than she could ever afford—all because she sought the power of the Risen and Eucharistic Christ in the fragile lives of homeless girls;

- her daring to walk with her sisters, as middleclass women, into and through Dublin’s worse slum districts, and to visit hovels where the poorest of the poor were sick and dying, so that she might tell them of the love and mercy of God;

- her going through miles of snow and mud in Birr in order to visit families long estranged from the church and to explain to them chapter 13 of Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians;

- and all the dignity and self-effacement of Catherine’s last year of life, a year of her own increasing illness and debility, during which she established two new foundations and prepared for a third, all the while teaching her sisters to bestow themselves “most freely” and to rely “with unhesitating confidence on the Providence of God” (Neumann, ed. 353).

Whether one looks at the beatitudes, the spiritual and corporal works of mercy, or the account of the last judgment in the Gospel of Matthew, one sees, in Catherine’s own life and in the lasting effect of her work, all that one could hope to see of prophetic utterance from, for, and of God. One can see why, on her death, her good friend Bishop Michael Blake said of her:

A more zealous, a more prudent, a more useful, a more disinterested, a more successful benefactress of human nature, I believe, never existed in Ireland since the days of St. Bridget. (Bermondsey Annals, in Sullivan, ed. 125)

(That is a span of 1300 years!)

But what of Catherine’s first associates—and the earliest Sisters of Mercy? What of their vocation to speak of, for, and from God?

The time is long past when we can do them justice. Despite their goodness in writing detailed Annals, when they were just as busy as we are, and despite the insights available in their archives, the full prophetic lives of these women are mostly hidden from us. We can catch only glimpses of their prophetic declarations of the mercy of God:

- Mary Vincent Harnett compiling a Catechism of Scripture History that was eventually used in Mercy schools throughout Ireland—probably the first such scripture textbook for Irish Catholic children;

- Mary Ann Doyle repeatedly begging the Bishop of Meath, unsuccessfully, to allow the sisters to visit the patients in the fever hospitals in Tullamore during an epidemic of typhoid;

- Frances Warde choosing to go to serve in the United States when she realized that her words and work in Carlow would never be understood by Bishop Haly of Kildare and Leighlin;

- Mary Clare Moore, Mary Francis Bridgeman, and twenty-one other Sisters of Mercy going, on very short notice, to Turkey and the Crimea to nurse wounded and dying soldiers during the Crimean War—and living there in barracks and tent huts, with unbelievably harrowing privations, illnesses, and squalor;

- Mary Winifred Sprey dying of cholera and Mary Elizabeth Butler dying of typhus—among sick and wounded soldiers in the Crimea to whom they had shown the tender face of God;

- Mary Gonzaga Barrie, Mary Stanislaus Jones, and other sisters struggling for over two years with Archbishop Henry Manning to keep open the hospital they had founded for incurable sick poor on Great Ormond Street in London;

- Mary Clare Moore corresponding with Florence Nightingale for almost twenty years, until Clare’s death, and sending her books of spiritual reading which Florence treasured: works by Gertrude the Great, Catherine of Siena, Teresa of Avila, and John of the Cross.

This list does not even begin to tell the story of our foremothers in Mercy. But of one thing I am sure, from all the evidence I have seen:

in the letters these women wrote to those they served,

in the places where they chose to live,

in their visits to the sick and dying and imprisoned,

in the classrooms where they taught,

in the adult instruction they gave,

in the hospitals where they nursed,

in their conversations with dying bishops and homeless orphans,

in their public appearance and in the example of their lives,

these women of Mercy explicitly spoke of, from, and for God. They used God’s name and spoke aloud of the God they understood. They were not timid about explaining God’s love for humankind; they were not reluctant to name the great mysteries of Jesus’ redemptive life; they were not afraid to declare publicly their own faith and hope in God, and their own confidence in the loving, active presence of God’s Spirit in the world. Their voices did not melt into the secular woodwork. They knew the explicit meaning and the prophetic vocation of their silver ring.

Catherine McAuley’s Silver Ring

The biblical precedent for our silver ring is not a wedding ring, but a signet ring. In the Old Testament, the finger ring was almost always a ring engraved with a seal. The seal was used to mark the personal authority vested in the wearer of the ring or to give personal authority to a document. The ring with its seal served as a signature and a pledge. It was vital to the authenticity of the seal that the clarity of its engraved image be preserved, and that the seal be kept on the person at all times.

When Catherine McAuley died, her silver ring was taken from her finger and subsequently given to Mary Juliana (Ellen) Delany when she professed her vows. Juliana eventually served in the Belfast community, and Catherine McAuley’s silver ring is now preserved there. At a gathering of Irish archivists on Baggot Street last June, those of us who were present had the privilege of holding and putting on Catherine’s ring. For each of us that silent encounter with Catherine’s ring was full of meaning. We put our own silver rings back on with much deeper understanding of what they mean and what they oblige.

Catherine’s silver ring has two mottoes engraved in it: on the inside, Mary’s words, “Fiat voluntas tua” (Thy will be done); and on the outside, the words, “Ad majorem Dei gloriam” (To the greater glory of God). I think these mottoes describe well her interior response to God’s call to prophecy and her public prophetic work—her utterances of, from, and for God. These mottoes speak of the interior purification of her desire and of the greater revelation of God’s mercy to which she gave her life.

We don’t have Catherine’s own ring here today. Her silver ring cannot be our ring. Her historical times are not our times, and she cannot live our prophetic vocation for us. But we can find in the example of her life the inspiration to take our own silver rings seriously, not simply as the record of a past event, but as the engraved seal and sign of a present reality and a present obligation.

In the ring of each of us is an engraved motto—one we chose “in our youth,” when we perhaps little realized the full call of the live coal of God’s word in our lives. It is perhaps time for us to examine those mottoes, those seals of God upon our lives. If these motto-words are still the voice of God for us, then let us live them. If these motto-words are no longer the language that most urgently expresses the empowering call of God in our lives, then let us re-engrave our rings with the purifying words of the voice calling us to prophecy.

Those who collaborate with us—as associates, coworkers, and followers of Catherine McAuley—are also joined to the pledge and meaning of these rings, in whatever ways they hear their own calls to prophesy God’s Mercy. They join the company of dozens of lay women and men without whose help the Sisters of mercy would never have been founded, and without whose continuing companionship the prophecy to which the community of Mercy is called will not be widely and visibly proclaimed.

What I have most wanted to stress in these reflections on the prophetic life and work of Catherine McAuley and the first Sisters of Mercy is the visible, audible of, from, and for God character of their prophetic voice. They moved through this world and were known in this world as women of God, women acting from God’s desire, women speaking for God and for God’s mercy.

And they understood themselves in that way:

- as messengers of God’s consolation,

- as bringers of God’s comfort,

- as defenders of God’s poor,

- as proclaimers of God’s realm,

- as teachers of God’s word,

- as nurses of God’s healing,

- as a human house of God’s Mercy.

When Catherine made new dresses for two hundred very poor little girls in Bermondsey; when she rejoiced to think of all the bazaar money in Limerick that would be changed into “bread and broth and blankets” for the poor (Neumann, ed. 275); when she grieved the deaths of three sisters in twelve days in 1840—in Dublin, Cork, and Limerick; when she struggled mightily to create a commercial laundry on Baggot Street, so that the girls and women in the House of Mercy would have a source of employment and income—in all these ordinary events of her life she sought to speak publicly of and for God and to nurture a visible prophetic community who by their words and deeds declared the revelation of God.

Reinvigoration

In speaking of the wonderful reinvigoration of Mary Aloysius Scott’s life, once she went to Birr as superior of the new foundation, Catherine said of Mary Aloysius’s former behavior: “We put our candles under a bushel” (Neumann, ed. 291).

Even now, Catherine does not want us to put our light under a bushel—as undemanding and unfatiguing as that might be—but rather to “let our light shine before others, so that they may see the good works of God and give glory to our God in heaven” (Matthew 5:16).

We perhaps have to ask ourselves whether our light has been, to some extent, under a bushel in recent years—our personal and corporate prophetic light. Has the prophetic call of our silver ring been somewhat hidden from public view? Has the visible seal of God’s claim upon our lives been somewhat blurred? Has our prophetic utterance been somewhat inaudible?

In June 1841, Bishop John England visited Baggot Street, hoping to recruit a community of Sisters of Mercy for a foundation in Charleston, South Carolina. Although Catherine could not spare any sisters at this time, she enlisted the smallest postulant in the community to play a joke on the bishop, and then described the fun in a letter to Mary Aloysius Scott:

After breakfast we assembled all the troops in the community room from all quarters—Laundry, Dining Hall, etc., etc. By chance 2 were in from Kingstown—we made a great muster. The question was put by his Lordship from the Chair: “Who will come to Charleston with me to act as Superior?” The only one who came forward offering to fill the office was Sr. Margaret Teresa Dwyer which afforded great laughing. I had arranged it with her before, but did not think she would have courage. His Lordship was obliged to acknowledge that we are poor dependents on the white veil and caps. We certainly look like a community that wanted time to come to maturity, reduced to infancy again as we are. (Neumann, ed. 347)

In the rhythm of the history of our prophetic call as Sisters of Mercy we are perhaps, once again, “reduced to infancy” and wanting “time to come to maturity.” May the God of all true utterance touch the lips of all of us with the live coal of the words and deeds God wishes us to utter.

Works Cited

Neumann, Mary Ignatia, RSM, ed. Letters of Catherine McAuley, 1827-1841. Baltimore: Helicon, 1969.

Sullivan, Mary C., RSM. Catherine McAuley and the Tradition of Mercy. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1995.

This article was originally printed in English in The MAST Journal Volume 8 Number 1 (1997).