If we wish to enter deeply into the prayer of Catherine McAuley, as a place where she and Christ may teach us, we may enter the ordinary scenes of her praying that have been recorded for us by those who lived with her. Whether we come in the early morning moonlight, or the noonday of ministry, or the late night darkness, we may in these scenes kneel with Catherine in God’s presence, and join our voices to hers as she prays the prayers that were most dear to her.

We may kneel with her in 1829, in the side room on Baggot Street, where she is gathered with the handful of companions who had joined her at the beginning of a God-calling, the full dimensions of which she little dreamed:

All rose at 6, but Revd. Mother and myself and sometimes Mother Frances used to rise at 4 and say the whole Psalter “by moonlight” often, read some of The Sinner’s Guide, and transcribe.[1]

We may kneel with her in 1832, in the makeshift hospital on Townsend Street in Dublin, in the midst of the devastating cholera epidemic:

There were always four there from nine in the morning till eight at night, relieving one another every four hours; and although our Reverend Mother had a natural dread of contagion, she overcame that feeling, and scarcely left the Hospital. There she might be seen among the dead and dying, praying by the bedside of the agonized Christian, inspiring him with sentiments of contrition for his sins, suggesting acts of resignation, hope, and confidence, and elevating his heart to God by charity.[2]

We may kneel with her in the mid 1830s, in the darkened chapel on Baggot Street, conscious perhaps of our own breaches of d1arity and of our lack of loving union with our Sisters:

Once it did happen that some disagreement took place, and although fatigued by the exertions of the day, she requested a Sister in whom she confided to remain with her in the Choir after night prayers that they might say the Thirty Days’ Prayer to obtain the restoration of peace and union, a circumstance which shewed in what a serious light she viewed the least breach of charity, since she never performed that devotion except in some important case; for she had a particular reliance on its efficacy, saying she was careful what she petitioned for by means of it, as the request was sure to be granted.[3]

Catherine McAuley was markedly reserved about her own spiritual life and personal prayer. Writing of her after her death, Mary Clare Moore says: “You ask about dear Revd. Mother’s spiritual exercises. She was too humble to talk much about self-indeed, she disliked the words my or myself so much that I often felt ashamed when inadvertently I had pronounced them.”[4] Similarly, Mary Vincent Harnett says of Catherine’s instructions to the first Sisters of Mercy:

She taught them to love the hidden life, laboring on silently for God alone; she had a great dislike to noise and display in the performance of duties. Often she was heard to say, “How quietly the great God does all His mighty works; darkness is spread over us, and light breaks in again, and there is no noise of drawing curtains or closing shutters.”[5]

Thus, in the only firsthand evidence we have—the contemporary biographical manuscripts about her and her own letters—Catherine does not describe her personal prayer, either orally or in writing. She may have shared her private prayer experience with her confessors or close priest friends (for example, Edward Armstrong, Michael Blake, and Redmond O’Hanlon, ODC) or with one or other of her good friends in the Sisters of Mercy (Clare Moore, Frances Warde, Elizabeth Moore, or Teresa White, for instance), but if these conversations occurred, their privacy has been preserved.

Catherine’s “Favorite” Prayers

We can, therefore, know nothing about the worded or wordless “I-Thou” utterances of Catherine’s heart to her God, except insofar as her interior prayer can be inferred, in a very indirect and limited way, from other features and expressions of her life. We will not hear the “curtains” or “shutters” of her inner hymns and psalms.

Yet there are many scenes in Catherine’s life that give us glimpses into the more public aspects of her prayer and reveal, in particula1 the depth of her devotion to a few “favorite” prayers found in the ordinary prayerbooks of her day-prayers which were, in her own vocal prayer and in the communal prayer of the community, central expressions of her zeal, confidence, and ardent love. These “favorite” prayers were, as Mary Clare Moore lists them: “The Thirty Days’ Prayer in honour of our divine Lord, and that also in honour of our blessed Lady. The Psalter of Jesus. The Universal Prayer [for All Things Necessary to Salvation]. The Seven Penitential Psalms, with the Paraphrase by Fr. [Francis] Blyth.” Clare says Catherine’s “Favourite Book” was “‘The Following of Christ,’ especially Chapters 30th of Book 3rd, and 8th of Book 4th.”[6] In the biography of Catherine inserted in the Bermondsey Annals for the year 1841, Clare gives a similar account of Catherine’s preferences:

She considered it most useful to adhere to a few solid spiritual works rather than to run over 1nany without reflection. The Following of Christ was one of her favourite books, also Blythe’s Paraphrase on the Seven Penitential Psalms; her Prayer book was that entitled Devotions to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Besides the spiritual exercises of the Community, at which she assisted with very great fervor; she had much devotion to the two Thirty Days’ Prayers, the Psalter of Jesus, and the Universal Prayer. Some passages of the last she used to repeat often, especially this: “Discover to me, O my God, the nothingness of this world, the greatness of heaven, the shortness of time, and the length of eternity.”[7]

The “Universal Prayer for All Things Necessary to Salvation” was composed by Clement XI during his papacy (1700-1721) and is included in William A. Gahan’s A Complete Manual of Catholic Piety, the prayerbook used in the Baggot Street community from the earliest days, as well as in other prayerbooks of Catherine’s day. This relatively short prayer expresses, in sixteen four-part petitions addressed to God, Catherine’s desire for God’s transforming help and her recognition that God is “my first beginning … my last end … my constant benefactor … [and] my sovereign protector.” As she prayed its petitions, the humility, simplicity, and purity of heart that characterized her spirit found expression in the straightforward words of this prayer. Later, out of deference to her or because the various Mercy communities occasionally prayed this prayer, the “Universal Prayer” was included in many nineteenth-century editions of the Choir Manual of the Sisters of Mercy.

“The Psalter of Jesus”

The “Psalter of Jesus” is a prayer that was especially dear to Catherine McAuley, though we may never fully grasp all that it meant to her. Evidently, as a child her “first attempt at writing was to try and print” this prayer.[8] We are told that when “she was still very young, before she knew how to write, she copied in a kind of large print passages from the Psalter of Jesus,” and that it was “a prayer for which she always retained great affection.” Later in her life, having memorized the fifteen paragraphs of petitions in the Psalter, she “used to repeat parts of it at different hours of the day, even when going thro’ the streets.”[9] In the years after the opening of the House of Mercy and before the founding of the Sisters of Mercy, Catherine and the community used to gather at eight o’clock in the evening to pray night prayers with the women in the House of Mercy and the people of the neighborhood who wished to join them. The prayers Catherine used each night “were those in the Catholic Piety with an additional Litany or the Psalter.”[10]

In October 1838, during the first months of the founding of the Limerick community, when they prayed that young women from the area might join the new foundation, Catherine wrote from Limerick to Frances Warde: “We finished the 2 30 Days Prayer on the 23rd—one in the morning and one in the evening—and are now going to say the whole Psalter for 15 days. This is our best hope.”[11] In the months of preparation prior to founding the Mercy community in Birmingham, England, Catherine followed a similar plan. As she noted on April 6, 1841: “We commenced the 30 Days Prayer on Thursday in place of the Psalter. The substance of [the] petition: that God will graciously direct all the arrangements to be made for the establishment of the Convent in Birmingham.”[12]

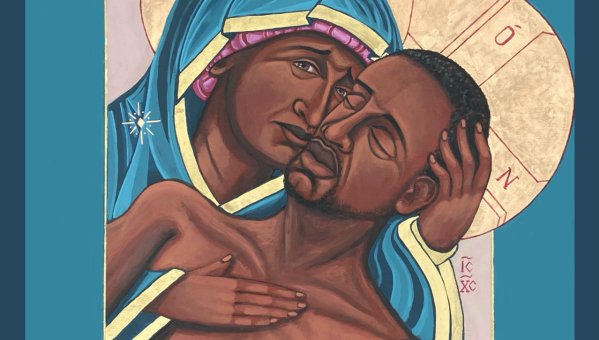

The Psalter of Jesus takes its inspiration and epigraph from Acts 4:12: “there is no other name under heaven … by which we must be saved”; it takes its title from its numerical similarity to the Psalter of the Hebrew scriptures, which contains one hundred and fifty psalms, and to the rosary (sometimes called the “Psalter of Mary”) which contains one hundred and fifty Hail Marys in its meditations on fifteen mysteries of Jesus’ life. The Psalter of Jesus reverently invokes the name of Jesus one hundred and fifty times. These invocations, distributed within fifteen petitions, are uttered in the biblical context of reflection on the death and the name of Jesus as honored in the letter to the Philippians: “he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross. Therefore God also highly exalted him and gave him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father” (2:8-11).

The fifteen petitions of the Psalter are grouped in three Parts of five petitions each. In William A. Gahan’s A Complete Manual of Catholic Piety, a prayerbook Catherine used, the editor advises those who pray the Psalter to apportion it through the day in whatever manner is most conducive to prayerfulness:

As it is not to be run over in too hasty a manner; but performed with the utmost reverence and recollection, the whole 1nay be said without interruption; or each Part, at three distinct periods of time, according to the leisure which persons may find after discharging the indispensable duties of their several states and conditions of life.[13]

Present-day users of the Psalter of Jesus sometimes choose to pray only one petition thoughtfully each day, for a period of fifteen days.

Anyone who meditatively prays the Psalter of Jesus can hear in its petitions the enduring desires and attitudes of disciples of Jesus. Beneath the datedness of some of the vocabulary and some of the theological formulations and emphases, one can feel the great Christian themes that spoke so strongly to Catherine’s spirit as she prayed this prayer: recognition of our personal weakness, and our need for God’s forgiving and enabling mercy; awareness of our subtle tendency to inconstancy and vanity, and our absolute dependence on God’s help; admiration and reverence for the person and mission of Jesus, and gratitude for his passion and death.

One can hear in the sentences of the Psalter of Jesus, if one lets their meaning sink in, all the hunger for single-heartedness, sorrow for sin, desire for God’s guidance, respect for Jesus’ goodness, and grief at his sufferings that characterized the mind and heart of Catherine McAuley. Although the language of the various petitions differs from that in present-day Christian prayers, the sentiments of the Psalter are the deep sentiments of the New Testament: grateful remembrance of the life and death of Jesus, in whom we are redeemed, and earnest desire to be, in the pilgrimage of this life, his authentic disciples.

The “Thirty Days’ Prayers”

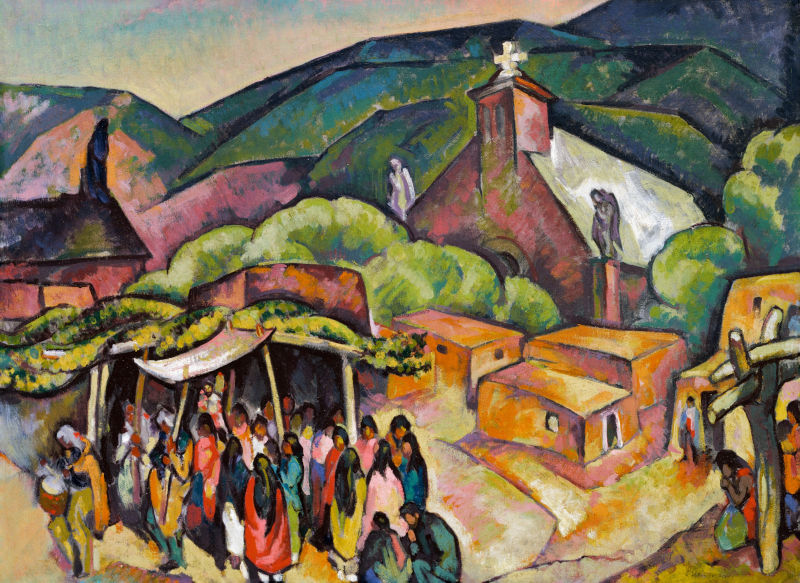

Although the early Sisters of Mercy often prayed the “Psalter of Jesus” communally, the Psalter is best regarded as a lifelong personal prayer of Catherine McAuley. This was not exactly the case with the two “Thirty Days’ Prayers”—one “To Our Blessed Redeemer, in Honour of His Bitter Passion” and one “To the Blessed Virgin Mary, in Honour of the Sacred Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ.” The Tullamore Annals for 1836 says of the Thirty Days’ Prayer to Mary: “Our Venerated Foundress made it a practice all through life, which she commenced in Tullamore, to remain a month on a new Foundation, during which time she always said the Thirty Days’ Prayer to our Blessed Lady to implore grace for the Sisters and a blessing on their work, through the intercession of the Mother of Mercy.”[14]

The biographical manuscripts about Catherine written by her contemporaries and her own correspondence all speak of her profound devotion to this prayer and to the version of it addressed to Jesus Christ. Clare Moore explicitly notes Catherine’s confidence in this prayer: “Whenever she was in doubt or difficulty she had recourse to prayer and the Thirty Days’ Prayer as long as I knew her was the means by which she obtained all she wanted. She used always say it with entire confidence of obtaining what she asked.”[15]

In the Bermondsey Annals, Clare says of Catherine and the Thirty Days’ Prayer:

she never performed that devotion except in some important case; for she had a particular reliance on its efficacy, saying she was careful what she petitioned for by means of it, as the request was sure to be granted. That devout prayer was always commenced by her on the first day of her arrival at a new foundation, and she endeavoured to remain at the place until it was completed.[16]

Catherine’s letters contain frequent references to the two Thirty Days’ Prayers—when she is in Limerick, Galway, and Birr and when she is preparing for the foundation in Birmingham. From Galway she writes to Frances Warde: “We said our two sweet Thirty Days Prayer, the one to our Saviour in the morning, to the B[lessed] V[irgin] in the evening. We did this also in London. My faith in it has increased very much.”[17]

Except for the opening paragraphs of these prayers, the two Thirty Days’ Prayers—to the Redeemer and to the Blessed Virgin Mary—are nearly identical in structure and content. After acknowledging with gratitude the divine embrace of our human nature in the conception and birth of Jesus, both prayers recount—from the perspective of Jesus’ experience or Mary’s—the chronological events of Jesus’ passion and death, his resurrection and ascension, the coming of the Holy Spirit, and the anticipated last judgment. Then, on the strength of all this testimony to God’s compassion toward humanity, the prayers provide an open opportunity to state the particular need or request for which God’s special help is now being sought. Here Catherine prayed for the spiritual and temporal welfare of the Institute, for women who might choose to enter the Sisters of Mercy, and for union and charity within the community. In the Limerick Manuscript, Mary Vincent Harnett notes that during the entire month of September, in which the Institute’s patronal Feast of Our Lady of Mercy occurs, Catherine “said in choir the Thirty Days’ Prayer in honor of the Blessed Virgin for the spiritual and temporal welfare of the Institute.”[18]

The passion of Jesus Christ constitutes the main content of the two Thirty Days’ Prayers. This emphasis corresponds with the intense reverence and compassion for the redemptive sufferings of Jesus that marked both Catherine’s personal spirituality and her ministry to suffering people. Her devotion to the passion of Jesus was not seasonal, but daily—even though such contemplation took a heavy toll on her. In the Bermondsey Annals, Clare Moore says: “She meditated with heartfelt attention the great mysteries of Faith—and feeling as she did so sensibly for the sufferings of her fellow creatures, her compassion for those endured by our Blessed Lord was extreme, so much so that it was a real pain to he, as she once told a Sister in confidence, to meditate on that subject.”[19]

But like Teresa of Avila, whom she admired, Catherine believed in the crucial importance to authentic Christian life of meditation on the gospel accounts of Jesus’ human life and death.

The longstanding, communal Mercy practices of honoring the passion of Jesus Christ on one’s knees at three o’clock on Friday and of standing for the light meal of gruel on Good Friday grew out of Catherine’s profound reverence for the final sufferings of Jesus. In her biography of Catherine published in 1864, Mary Vincent Harnett, who had lived with Catherine at Baggot Street, says of her on Good Friday:

On that day she entirely abstained from food, though she used to remain in the refectory sometimes, as if she were partaking of the light collation which she had prescribed for the Sisters, and which they take standing, the seats being removed according to the custom she established. She could not endure the appearance of a regular meal on the anniversary of our dear Lord’s death, or to have any cooking done in the establishment that day.[20]

The Penitential Psalms

Finally, among Catherine’s “favorite” prayers are the penitential psalms—the ancient, classic psalms of repentance for sin and confident appeal to God’s mercy. At least since the sixth century, the penitential psalms have been identified as seven: in the Vulgate numbering that Catherine would have used they are Psalms 6, 31 (NRSV 32), 37 (NRSV 38), 50 (NRSV 51), 101 (NRSV 102), 129 (NRSV 130), and 142 (NRSV 143). The long tradition of praying the De Profundis (Psalm 130) daily in all communities of Sisters of Mercy—”Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord. Lord, hear my voice!”—surely evolved from Catherine’s devotion to these seven psalms, as did the frequent communal praying of the Miserere (Psalm 51). Catherine’s main aid in understanding these psalms was Francis Blyth’s A Devout Paraphrase of the Seven Penitential Psalms: or, A Practical Guide to Repentance.[21]

Blyth’s small book contains the complete texts of the seven psalms, accompanied at the bottom of each page by amplifications of the meaning of each verse. The tone of his volume is gracious, focusing on the merciful love of God which is promised to those who recognize their true dependence on God’s goodness. The “penitence” of these psalms is not the so-called “guilt-trip” feared and shunned by many present-day students of the spiritual life, but rather the saints’ truthful and peaceful acknowledgment of their radical need for God’s forgiveness, for God’s redemptive bridging of the gap between their spotty human virtue and God’s clean holiness. This kind of penitence gave serenity and courage to the heart of Catherine McAuley, silently impelled her through the streets of Dublin, and allowed her to feel the deepest sorrow of those she visited and served. Often she would have prayed: “Create in me a clean heart, O God, and put a new and right spirit within me … a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise” (Psalm 51:10,17)—the same psalm verses Teresa of Avila is said to have prayed as she was dying.

Catherine’s Principles

In personal and communal prayer, Catherine McAuley seems to have favored three principles: simplicity of language, restraint in the choice of communal prayers, and subordination of prayer to the works of mercy. Her contemporaries were well aware of her discomfort with “highflown” language. In the Bermondsey Annals, Clare Moore writes:

She loved simplicity singularly in others, and practised it herself, telling the Sisters to adopt a simple style of speaking and writing … Even in piety she disliked highflown aspirations or sentences, and to a Novice, who was writing something very exalted in that way, she observed, how much more suitable those simple phrases found in ordinary prayers would be, and then suggested as a favourite of her own, “Mortify in me, dear Jesus, all that displeases Thee, and make me according to Thine own heart’s desire.”[22]

Clare Augustine Moore, living at Baggot Street in Catherine’s day, tells an instructive story about Catherine’s restraint in the choice of communal prayers. She describes Catherine’s use of certain prayers in The Soul United to Jesus by Ursula Young, OSU:

She loved to pray before the Most Holy Sacrament and finding that in Carlow they used after the mid-day prayers one of the beautiful “Effusions of Love” at the end of The Soul United to Jesus, she liked them so well that she began to use them herself. After a month, however, she ceased this devotion and when I asked her why said that if she added prayers herself some very devout successor would add more and another more till, especially in poor convents, the Sisters would be incapable of the duties of the Institute … Still she told me she would always use these prayers herself and advised me to do the same.[23]

The short “Effusions of Love” in the back of Ursula Young’s prayerbook have the ardor, zeal, humility, and confidence that must have characterized Catherine’s personal prayer. One can imagine why she initially wanted her community to pray these prayers together, but one can also admire her restraint in not adding to the prescribed communal prayers.

For Catherine always regarded specific times of prayer, both personal and communal, as subordinate to the requirements of the works of mercy. While she did not intend that the Sisters should casually excuse themselves from the times proposed for prayer she insisted, especially in her essay on the “Spirit of the Institute,” that in a religious congregation like the Sisters of Mercy, and in the practical order, the “duties” of Mercy have an overriding religious priority:

We ought therefore to make account that our perfection and merit consists in acquitting ourselves well of these duties, so that though the spirit of prayer and retreat should be most dear to us, yet such a spirit as would never withdraw us from these works of mercy, otherwise it should be regarded as a temptation rather than the effect of sincere piety. It would be an artifice of the enemy, who … would endeavour to withdraw us from our vocation under the pretence of labouring for our advancement.[24]

On the contrary, Catherine believed that prayer was the constant servant of ministry: “We ought to give ourselves to prayer in the true spirit of our vocation, to obtain new vigour, zeal and fervour in the exercise of our state.”[25]

Times of personal or communal prayer simply gathered to explicit concentration the ongoing contemplative prayer that, of necessity, always accompanied the works of mercy.

Given the nature, difficulties, contexts, and goals of the works of mercy—if they were indeed works of God’s mercy—these works could not, in her view, be accomplished except by a minister who moved forward in an attitude of prayer, relying on God’s guidance and help. Thus, Catherine believed, “the corporal and spiritual works of mercy, which draw religious from a life of contemplation, so far from separating them from the love of God, unite them more closely to Him, and render them more valuable in His holy service.”[26]

The “favorite” prayers of Catherine McAuley are faithful to these principles. The language, though occasionally archaic by present-day standards, is not ornate or hyperbolic; and the theological concepts, though sometimes needing present-day nuances, are in fact mainstream elements of Christian faith and relationship to God. Secondly, the prayers are few in number; and were not all used simultaneously as communal prayers: they were used occasionally, perhaps even frequently, to express the special needs and hopes of the communities. And finally, all of these prayers are biblical and apostolic in their language and outlook: they focus on the revelation of God’s mercy and on the merciful life and mission of Jesus.

Communal Prayer of the Sisters of Mercy

The new Morning and Evening Prayer of the Sisters of Mercy will, in time, be supplemented by a small volume tentatively entitled Praying in the Spirit of Catherine McAuley. This volume will contain, in addition to other prayers in the Mercy tradition, adaptations of the “Psalter of Jesus,” the “Thirty Days’ Prayers,” and the “Universal Prayer for All Things Necessary to Salvation,” as well as the original texts of these prayers, as Catherine would have prayed them, and an invitation to develop one’s own adaptations.

The desire to pray in the spirit of Catherine McAuley, whether it is a personal or communal desire, is not a sentimental attempt to recreate a theological time and place that is past or to imitate one’s founder in some superficial way. Rather it is a desire born of docility: a confident readiness to be taught anew by the woman who, in a singular way, most deeply understands and cherishes the Sisters of Mercy and their Associates.

The Sisters of Mercy have not multiplied communal prayers in recent years. The recognized need for the two volumes noted above is evidence of that. Moreover, the once strong petitionary prayer of the Institute—the communal prophetic outcry of Mercy women the world over who were committed to the works of mercy and the reign of God’s justice—may now appear more mute to the world than it really is, for lack of specific prayer prayed in common. The continued renewal of our visible and audible communal prayer life will have many facets. Perhaps one small element of this renewal may be a docile return to prayers Catherine McAuley prayed, or to slight adaptations of them that preserve their intent while modifying their vocabulary (even simply changing the Thee’s and Thou’s does much to modernize them).

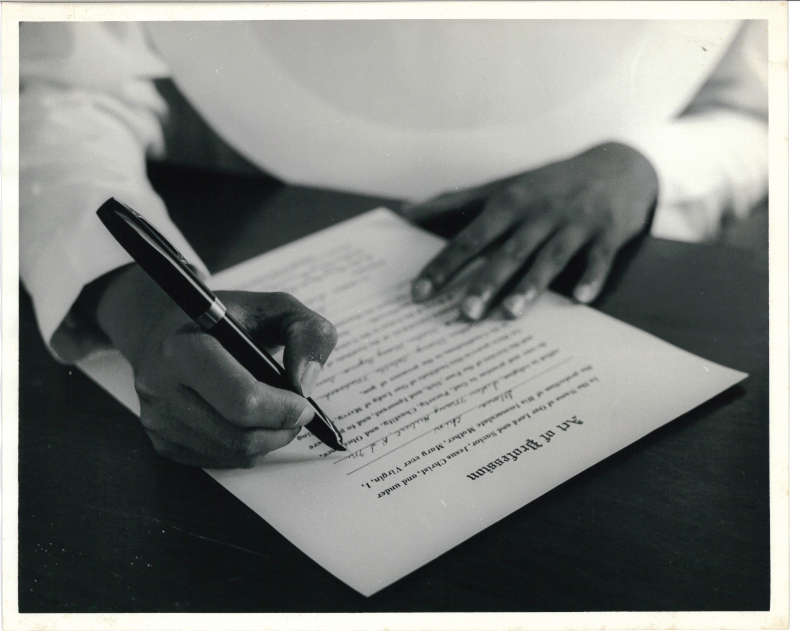

Whether we kneel with Catherine in the early morning moonlight, at the bedside of the world’s grave illnesses, or in the dark chapels of the night, she will support our personal and communal prayer as ardently as she once encouraged our renewal of vows:

“When we first make our vows [she would say] it is not surprising if we feel anxious, and pronounce them in a timid, faltering voice, being as yet unacquainted with the full extent of His infinite goodness to whom we engage ourselves for ever; but when we renew them it ought to be with that tone of JOY and confidence which the experience of His increasing mercies must inspire.” This feeling was easily discerned in her manner of reading the Act of Renewal, and also in the joyful way in which she repeated the usual Te Deum afterwards.[27]

Notes

[1] Mary Clare Moore to Mary Clare Augustine Moore, 23 August 1844, in Mary C. Sullivan, Catherine McAuley and the Tradition of Mercy (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1995) 85.

[2] Mary Clare Moore, “Bermondsey Annals,” in Sullivan, 112.

[3] Ibid., 116.

[4] Mary Clare Moore to Clare Augustine Moore, 1 September 1844, in Sullivan, 92.

[5] “Limerick Manuscript,” in Sullivan, 174.

[6] A Little Book of Practical Sayings, Advices and Prayers of our Revered Foundress Mother Mary Catharine [sic] McAuley, ed. Mary Clare Moore (London: Burns, Oates, 1868) 34-35.

[7] “Bermondsey Annals,” in Sullivan, 116.

[8] Mary Clare Moore to Clare Augustine Moore, 1 September 1844, in Sullivan, 92.

[9] Mary Vincent Harnett, “Limerick Manuscript,” in Sullivan, 140.

[10] Clare Augustine Moore, “A Memoir” in Sullivan, 201.

[11]Letters of Catherine McAuley, ed. Mary Ignatia Neumann (Baltimore: Helicon, 1969) 141.

[12] Catherine McAuley to Mary Cecilia Marmion, 6 April 1841, in Neumann, ed., 327.

[13] “The Psalter of Jesus,” in The Christian’s Guide to Heaven, or A Manual of Catholic Piety, ed. William A. Gahan, OSA (Agra: Agra Press, 1834) 92. There were, of course, earlier Irish editions of Gahan’s prayerbook, including one published by T. M’Donnel in Dublin in 1804 with the sub-title, A Complete Manual of Catholic Piety, but library copies of these are very rare and photocopying their pages is not permitted. “The Psalter of Jesus” is on pages 92-105 of the 1834 edition.

[14] “Tullamore Annals,” in Sullivan, 66-67.

[15] Mary Clare Moore to Clare Augustine Moore, 1 September 1844, in Sullivan, 93.

[16] “Bermondsey Annals,” in Sullivan, 116.

[17] Catherine McAuley to Frances Warde, 30 June 1840, in Neumann, ed., 219.

[18] “Limerick Manuscript,” in Sullivan, 182. The complete texts of the two Thirty Days’ Prayers are contained, for example, in The Golden Manual: or, Guide to Catholic Devotion, Public and Private (London: Burns & Lambert, n.d.) 438-44.

[19] “Bermondsey Annals,” in Sullivan, 117.

[20] [Mary Vincent Harnett], The Life of Rev. Mother Catherine McAuley, ed. Richard Baptist O’Brien (Dublin: John F. Fowler, 1864) 113.

[21] The seventh edition of this book was published in Dublin by The Catholic Book Society in 1835, but Catherine presumably had an earlier edition. Since Blyth (1705?-1772) was a Carmelite, she may have received a copy from one of her Carmelite friends in Dublin.

[22] “Bermondsey Annals,” in Sullivan, 111.

[23] Clare Augustine Moore, “A Memoir,” in Sullivan, 213.

[24] Catherine McAuley, “Spirit of the Institute,” in Neumann, ed., 389. Catherine is here dependent on the treatise of Alonso Rodriguez (1526-1616), “Of the End and Institution of the Society of Jesus,” in his The Practice of Christian and Religious Perfection, vol. 3, published in English translation in Kilkenny, Ireland, in 1806. Catherine transcribed her much-abbreviated essay from this source. Please see my “Catherine McAuley’s Theological and Literary Debt to Alonso Rodriguez: The ‘Spirit of the Institute’ Parallels,” Recusant History 20 (May 1990) 81-105.

[25] Ibid., 389.

[26] Ibid., 387.

[27] “Limerick Manuscript,” in Sullivan, 183.

This article was originally printed in English in The MAST Journal Volume 8 Number 3 (1998).