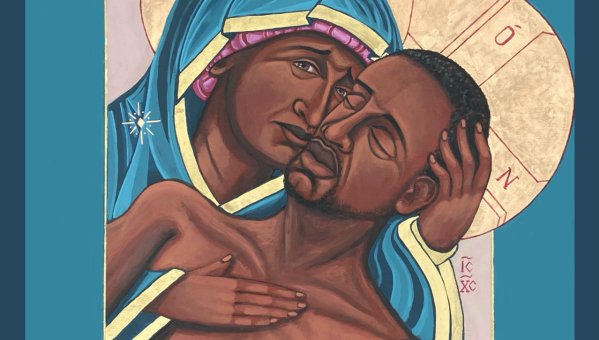

As a feminist theologian, Mary Aquin O’Neill wrote Original Grace: The Mystery of Mary out of a committed devotion to Mary and a commitment to women. She was very aware that the images of Mary developed over the years by male theologians simply deepened an understanding of women as inferior. In Christianity Jesus is the lone redeemer. All women as well as men are subordinate to him, but in Catholic Christianity only men have the opportunity to be ordained to preside in Jesus’ image. Men can celebrate the Catholic liturgy repeating for their congregants the words of Jesus, ‘this is my body, this is my blood given for you.” Woman are barred from such and, while there has been significant conversation about the gifts women bring to the church even the most recent synod remained ambivalent about proper liturgical roles for women.

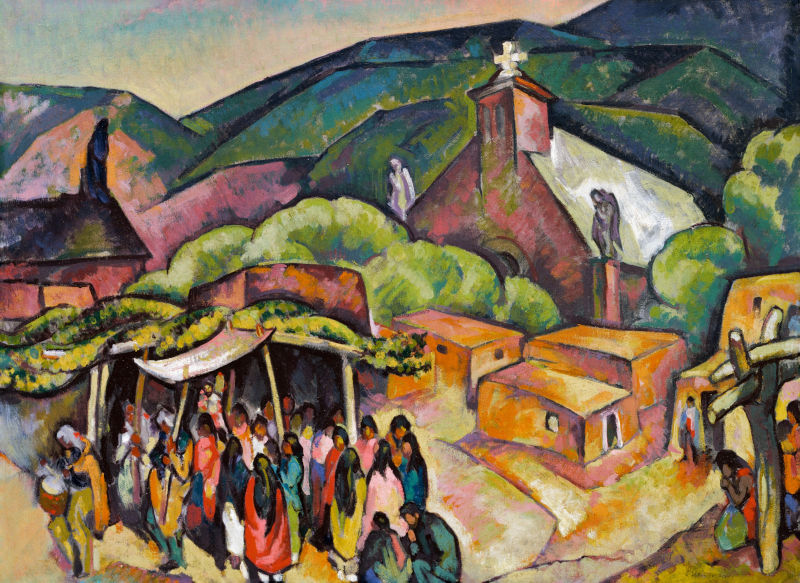

O’Neill argues that “What Christianity needs…are images that can destroy any theology that privileges one sex over another…For there to be true complementarity in the body of Christ, the roles and the mission of Mary must come to be seen as a dimension of the redemptive activity of God, in tandem with her son’s.”[i] O’Neill is after images of Mary that reflect in female form “one who is human to the utmost, to the point where humanity and divinity are united in her.”[ii] Thus, she asserts that re-imagining Mary through the lens of a ‘productive imagination’ that gets behind and beyond the rational (e.g. historical critical method) would be liberating for the Church and for women. The book reviews the New Testament Scriptures, ancient texts, Marian devotion throughout the ages, and church dogma. Moving beyond settled understandings and boundaries but staying within the tradition, she re-interprets it to show that Mary is as much a partner with God in redeeming humankind as Jesus is. Finally, she speaks to the liturgical cycle, illustrating interlocking narratives of the woman and the man. “…the devotional feasts that concentrate on one or other aspect of the man’s meaning for Christians are matched by corresponding feasts that show a similar significance for the women.”[iii] (112)

| Commemorations of Mary | Commemorations of Jesus |

| Immaculate Conception (December 8) | Annunciation (March 25) |

| Birth (September 8) | Christmas (December 25 |

| Holy Name of Mary (September 12) | Holy Name of Jesus (January 3) |

| Presentation in the Temple (November 21) | Presentation in the Temple (February 2) |

| Sorrows of Mary (September 15) | Good Friday |

| Assumption (August 15) | Ascension Thursday |

| Queenship of Mary (May 31) | Christ the King |

| Immaculate Heart of Mary (August 22) | Sacred Heart of Jesus |

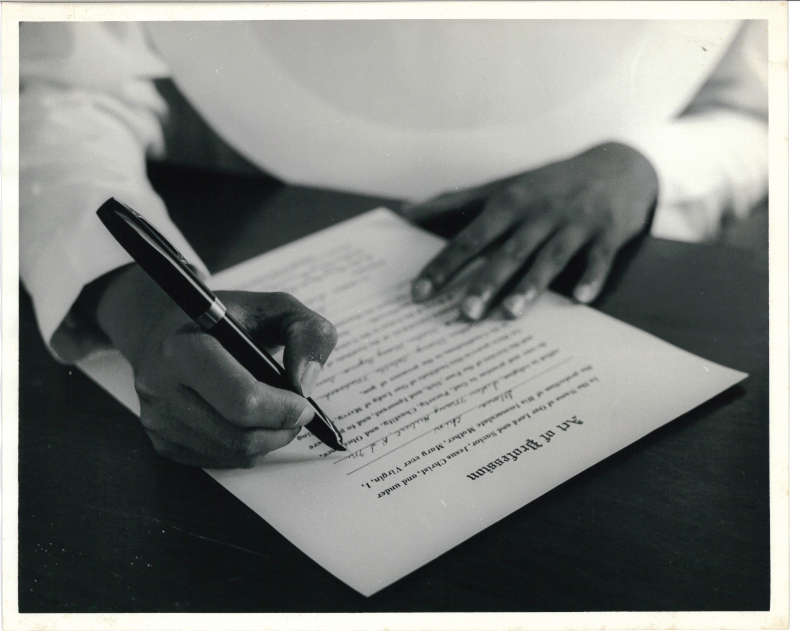

Reading O’Neill one could choose to think she is simply blinded by her own desire for women to be fully recognized within the church. Or one can trust her true devotion to Mary and her careful scholarship and be led to wonder about how closed we can become to change, that is, unable to rely on anything more than our ‘re-productive’ imagination, that is an imagination unable to escape from previous learnings and current understandings. What would allow us to go beyond and develop our doctrine about Mary so that one with a woman’s body could be understood as revered as much for her faithfulness to God as Jesus is. Thus, in the light of O’Neill’s argument about Mary, a woman willing to give over her body and the rest of her life to the designs of God, I became interested in one of her traditional titles, that of co-redemptrix, ascribed to her as early as the 14th century and used to identify Our Lady’s unequaled cooperation in redemption by popes, saints, mystics, bishops, clergy, theologians, and the faithful People of God, including by recent saints including St. Pio of Pietrelcina, St. Maximilian Kolbe, St. Maria Benedicta of the Cross, St. Josemaría Escrivá, St. Teresa of Calcutta, and, most recently, by Pope St. John Paul II. However, the term when used has been interpreted to mean that she only cooperated with the Redeemer. For example, in a 1917 document published during the Fatima centenary, the Theological Commission of the International Marian Association requested that Mary be officially, dogmatically named ‘co-redemptrix , but throughout their presentation they are careful to note that Mary’s human participation in Redemption is “entirely dependent upon the unique Redemption achieved by the Word made flesh, relies wholly on his infinite merits, and is sustained by his one mediation. Mary’s sharing in the redemptive mission of her Son in no way obscures or diminishes the unique Redemption of humanity accomplished by Jesus Christ but rather serves to manifest its power and fruits.”[iv] While using the prefix ‘co’ would imply in modern English exactly that which O’Neill is asserting, the traditional interpretation attached to the use of the word said otherwise. But more recently, controversy has emerged about the use of the title. When Pope Benedict XVI was Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger he was quoted as saying , “The formula ‘co-redemptrix’ departs to too great an extent from the language of Scripture and of the Fathers, and therefore gives rise to misunderstandings.”[v] Pope Francis reiterated the concern saying on March 25, 2021, the feast of the Annunciation and referring to the title, “we need to be careful: the things the Church, the saints, say about her, beautiful things, about Mary, subtract nothing from Christ’s sole Redemption. He is the only Redeemer. They are expressions of love like a child for his or her mamma — some are exaggerated. But love, as we know, always makes us exaggerate things, but out of love.”[vi] Then, that same year in his spontaneous, unscripted homily on the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe in December, Francis said, “Faithful to her Master, who is her Son, the unique Redeemer, she never wanted to take anything away from her Son. She never introduced herself as co-redemptrix. No. [she is a] disciple.”[vii] Some commentators indicate that Pope Francis thought the use of the title simply foolish.

Does the church protest too much? Remembering that the best gift for a critical mind is a new question, perhaps O’Neill has uncovered what Johannes Metz termed a ‘dangerous memory,’ that is, a way to re-read the Christian tradition about Mary that would keep open the possibility of her truly being the co-redeemer and thus allow for the development of doctrine regarding women’s role in the church. Dangerous memories are seeds of resistance to the status quo and provide hope for the marginalized because they trigger an understanding that reality, institutions and societies could be other than they currently are.[viii]

Mary was a first century Mediterranean woman, the mother of Jesus, but we really know little about her. Paul’s letters, the earliest written testimony to Jesus do not mention her; our understandings mostly stem from the infancy narratives of Matthew and Luke. These late 2nd century narratives present her as a virgin called by God through the angel Gabriel to bear the child, Jesus. Ignatius of Antioch, also writing in the 2nd century, affirms her as mother of Jesus the Christ and, once the 325 A.D. Council of Nicea dogmatically stated that Jesus was God, she began to be more prevalent in art and early liturgies leading to the affirmation of her as Theodokis, that is, Mother of God, at the Council of Ephesus in 431 A.D. But what did it mean to be a mother in the first century middle Eastern culture?

From cultural anthropology we learn that until very recently in human history, fatherhood indicated the primary, essential and creative role in child begetting while motherhood indicated bearing. To be named father was to be understood as the one who planted the seed in the field, the womb. The seed was the sole determining factor of the substance, the child. The womb, ever renewable soil, nurtured the seed if it was fertile. However, the defining feature of the field was not what it provided for the seed (fertility), but rather who owned it (security). The woman’s womb, the field, must guarantee the security of the male patriline, the extension of which was a son. The blood and the milk from the mother swelled the being of the child but in no way affected the identity of the child. Even though the womb is necessary to transform the seed, women’s contribution was understood as temporal; the woman could not create and project herself beyond this life. Thus, these understandings of birth and sex informed the symbols of early Christianity. And, lest we underestimate the power of this thought pattern persisting even today in industrialized, modern countries, consider that much of our literature about the possibilities of conception refer to males as potent or impotent and females as fertile or infertile. It should come as no surprise that these cultural beliefs about begetting are congruent with patriarchy in our church and also what could make the title of co-redemptrix a dangerous memory within the church, a memory resisted by those desiring the continuance of patriarchal structures.[ix]

The discovery of the ovum did not occur until the 17th century and the understanding that the woman’s body yielded essential elements to the process of conception and birth wasn’t fully understood until the late 18th century when microscopes were widely in use. From science we now know that the ovum carries the female’s genetic material (23 chromosomes) which combines with the sperm‘s genetic material (23 chromosomes) during fertilization to create a new organism with a unique set of genes. Thus, because of science, the seed of the male is no longer understood to be the sole determining factor of the child.

We also know that doctrines, dogmas, traditions and interpretation are all human formulations. Over the years all of these human formulations helped, of course by the Holy Spirit, have evolved, albeit slowly, to meet the needs of the signs of the times. This doesn’t happen because of knee jerk reactions but rather because of necessary and studied reflection upon human experience that enriches the Christian faith lest it become the dead faith of the living rather than a living faith inspiring us to live as Jesus did and risk charity, peace, patience, and kindness. A clear sign of the times is the struggle of women around the world and within the church to be rightly recognized for their gifts and talents and free from patriarchy. Official Catholic structures as they relate to men and women have been based on the understandings of procreation dating from early middle Eastern culture.

| WOMEN | MEN |

| Receivers, temporal | Authors of life as God is |

| Not part of apostolic transmission | Author of world, possess seed; transmit word of God; Name, create apostolic succession |

| Reproductive | Productive, creative power objectified in institutions |

Because God’s creative power is transmitted only through the seed of man, males can ordain other males and provide for apostolic succession. The role of women is to be open and receptive, not creative. Church tradition was developed in a world in which women could not author new human life, thus they could not author institutional life. Women’s role is to reproduce that which is ordained by God and transmitted through men. Patriarchy, as the “glorification of the father,” follows from perceiving the creative source for life in the male who is symbolically allied with God. Not only is there only one personal principle animating the universe, that one principle is masculine.

If Mary was as O’Neill urges an equal partner with Jesus, as men and women are now understood to be co-partners in bearing new life, the title co-redemptrix and all that O’Neill, without using the title, argues that it means, could lead to an evolution within the church to recognize the rightful place of women as full partners in the current work of contributing to the reign of God. While I am not sanguine about prospects for Catholic ordination to be open to women anytime soon, I do think reflection on O’Neill’s argument about Mary as well as questioning why the title co-redemptrix has, in recent years, become verboten is worthy of our time.

[i] Aquin O’Neill, Original Grace: The Mystery of Mary. Cascade Press, 2023, p. 6, 45.

[ii] Original Grace, p. 45.

[iii] O’Neill, Original Grace, p. 74, 112.

[iv] Theological Commission of the International Marian Association, Ecce Mater Tua, Jan 1, 2017, #2.

[v] God and the World: A Conversation with Peter Seewald, Ignatius Press, 2000, p. 306

[vi] Pope Francis, homily, Feast of the Annunciation, March 25, 2021.

[vii] Pope Francis, homily, Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, December 12, 2021.

[viii] Johannes Metz introduced the term ‘dangerous memory’ in his Faith in History and Society; Toward a Practical Fundamental Theology, 1970.

[ix] The material on cultural anthropology is published in an article I did when I was teaching theology at Creighton University. See Maryanne Stevens, “Paternity and Maternity in the Mediterranean: Foundations for Patriarchy,” Biblical Theology Bulletin, Vol. 20, No. 2 (1990).

image: Statue of Mary in the church of Saint Mary in Canterbury, Kent