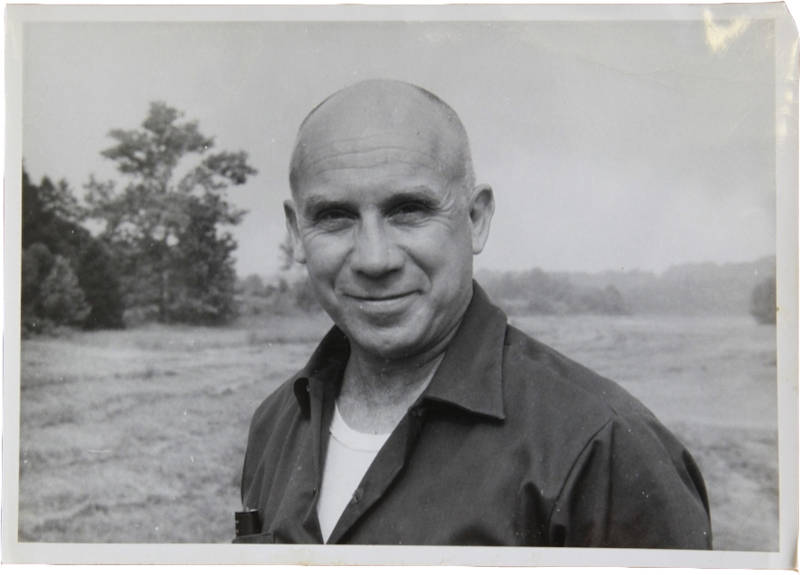

This reflection paper has been adapted from presentations to the staff at Carmel College, Auckland, New Zealand (2023), and the Institute of Our Lady of Mercy, UK, (2024).

It has been a long time since I listened to a news program that did not mention war, most recently the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and that between Ukraine and Russia. Participating in a war from which they may never return, the predominantly male soldiers are portrayed as courageous. Why is responding with violence portrayed as courageous? In this paper, I examine the root of the word courage before using Catherine McAuley’s writings to offer a different model for courageous leadership, focusing on Catherine’s courage to encourage.

The Latin word for courage is virtūs. In Roman mythology, Virtus was the deity of battle, represented by a soldier standing in armour on his shield and sword. Latin scholars will also identify that vir is the word used to describe a man, so the etymology identifies the virtue as masculine. When naming the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit, the word courage is sometimes called fortitude. The definition in the Catechism of the Catholic Church says, “The virtue of fortitude enables one to conquer fear, even fear of death, and to face trials and persecutions,” language that implies a battle.[1] The Latin root of the word fortitude comes from fortis, meaning strength.

Too often, society has presented courage in a way that emphasizes the masculine, the battle-worthy, and the strong. Moral philosopher Geoffrey Scarre claims that this image of courage “is antithetical to compromise, conciliation and the search for peaceful solutions to problems. Courageous people may incline to fight when they should talk and dig in their heels rather than see what can be accomplished by goodwill and diplomacy.”[2]

L. Frank Baum’s depiction of the Cowardly Lion in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, published in 1900, emphasises the Lion’s understanding of the element of courage which is bravery. The Lion faced danger and responded with kindness and generosity when he did not think he had courage. After the Lion took the unknown courage potion given to him by Oz, the wizard, the Lion displayed his courage aggressively. Oz, however, claimed that true courage stems from having confidence in oneself and, therefore, being able to face danger when afraid.

“But how about my courage?” asked the Lion anxiously. “You have plenty of courage, I am sure,” answered Oz. “All you need is confidence in yourself. There is no living thing that is not afraid when it faces danger. The true courage is in facing danger when you are afraid, and that kind of courage you have in plenty.”[3]

In French the word is le courage, referring to le coeur or the heart—the “place” associated with one’s innermost feelings and temper. The definition of courage in the Western linguistic tradition is about displaying the innermost feelings of the heart.

True courage as described by the Wizard of Oz, referring to the innermost feelings of the heart, is evident in the actions and writings of Catherine McAuley. The following stories demonstrate that Catherine was brave, strong, and diplomatic; she used words instead of swords and undertook ministries despite the possible dangers. Catherine’s reliance on God was a significant source of the courage she demonstrated. Also evident in Catherine’s writings is her ability to encourage and help others to see the courage they possess and, therefore, to act; on Catherine’s part, this demonstrates leadership.

Application to the Writings of Catherine McAuley: Courage to Begin

My father is an avid fan of the Western film hero, John Wayne, who once said, “Courage is being scared to death—but saddling up anyway.”[4] Courage is not about lacking any sense of fear but, rather, drawing inner strength from prior experiences that give a person the confidence to take a chance on another venture, even if one is scared.

The story of the foundation to Tullamore was an exceptionally courageous venture for Catherine. Elizabeth Pentony was a laywoman with a generous annuity that she used to relieve people in poverty in Tullamore. When she died, she left her property for any religious congregation that would come to Tullamore. The Sisters of Charity were not convinced to undertake this foundation because the actual funding was so limited. The Sisters of Mercy were subsequently invited. While there was the gift of the house in Tullamore, there was no guarantee of funding ongoing works themselves. Nevertheless, Catherine still agreed to the foundation, reportedly saying, “If we do not take Tullamore, no other community will.”[5]

Catherine was already involved in the various ministries operating from the House of Mercy on Baggot Street. Additionally, the sisters were using the branch house at Kingstown for respite.[6] However, the circumstances in Tullamore were different. Baggot Street was purpose-built with the substantial inheritance from William and Catherine Callaghan. Tullamore was a house with rooms “so small that two cats could scarcely dance in them,” and it was to be a separate foundation rather than a branch house.[7]

Establishing a new foundation meant Catherine would lose Mary Ann Doyle and a novice, Teresa Purcell. Mary Ann had been Catherine’s first companion in ministry at Baggot Street, had completed the novitiate at George’s Hill with Catherine and, in 1832, had tirelessly nursed with her at the cholera depot. The annals of the time record that Mary Ann Doyle was “a great loss to the young institute and a painful separation for the holy foundress.”[8]

The Tullamore foundation was courageous because it was the first foundation after Baggot Street. There was no blueprint. The risk of failure was high. If the Tullamore foundation did not flourish, it did not augur well for future foundations. In Catherine, Carmel Bourke says, “we find an amazing act of daring; she made her first foundation with only one professed sister and a novice.”[9] Bourke goes on to describe the appointment of Mary Ann as the novice director for the three postulants joining Tullamore as even more daring. How easy it would have been for Catherine to have brought the postulants back to Baggot Street and to oversee their formation herself.

However, there was wisdom in the postulants remaining in Tullamore. In 1838, Catherine was to write to Frances Warde saying, “Every place has its own particular ideas & feelings which must be yielded to when possible.”[10] The postulants were local women who had worked alongside Elizabeth Pentony in the ministry in Tullamore. Therefore, they had a better understanding of the “ideas and feelings” of Tullamore, which would have helped the mission to succeed.

Sending Mary Ann Doyle to Tullamore and giving her complete autonomy reflected Catherine’s courageous leadership. Catherine demonstrated the courage to encourage. Catherine’s faith in Mary Ann would have increased her confidence. How many individuals, with such a vested interest in the organization as Catherine had, would have had the courage to hand over a new foundation to another entirely? Catherine would have recognized that Mary Ann’s experiences had prepared her for this moment. Therefore, she could entrust Mary Ann with undertaking the task of superior.

Limerick Foundation

A similar situation occurred with the Limerick foundation. Eager, enthusiastic Elizabeth Moore was excited about the new foundation Catherine had selected her to lead. However, her fears overwhelmed her when the situation became a reality. Catherine wrote,

As to Sister Elizabeth, with all her readiness to undertake it – we never sent forward such a feint-hearted [sic] soldier, now that she is in the field. She will do all interior & exterior work, but to meet on business – confer with the Bishop – conclude with a Sister – you might as well send the child that opens the door. I am sure this will surprise you. She gets white as death – and her eyes like fever.[11]

Elizabeth had much to fear, other congregations having failed to establish a presence in Limerick. Again, we see Catherine’s trust in the readiness of the women selected to lead the foundations. Catherine did not replace Elizabeth when fear overcame the young woman. Instead, she stayed alongside her longer than planned to support and encourage Elizabeth in the new ministry. On her eventual departure from Limerick, Catherine was to leave her further words of encouragement in a poem, the first line urging Elizabeth not to “let crosses vex or tease” and to be courageous in responding to trials.[12]

The narration of the foundation to Birr in 1840 gives a third example. Catherine selected Aloysius Scott as the superior, a woman who had previously had several health issues and appeared quite frail. In a letter to Cecilia Marmion, Catherine describes how Aloysius had taken to the mission (even to pick up an iron sledge) and reflects on her gratitude to God for the courage to encourage her.

Sister Aloysius has just called me with a great iron sledge in her hand. She saw, through a small aperture, a long room, instantly broke through a slight partition, and discovered a spacious apartment with cornice, skirting, grate & chimney piece – 3 windows – full as large as our present community room. The Bishop when residing here – not requiring so much room – gave it up for oats and hay – getting up by a ladder to one of the windows. It will make 6 fine cells. She is now making out a House of Mercy – of stable and coach house. I never cease thanking God for giving me courage to bring her into action, and she is delighted.[13]

Leadership is a courageous task. When the organization’s success is at stake, it is tempting for a named leader of an organization to undertake the work themselves to keep control and ensure success, especially when a venture is risky. Yet, Catherine realised that this would not be to the benefit of the mission. Catherine could not be everywhere, so she needed the courage to trust others, ensure they were prepared, and do all she could to encourage them in their work.

Catherine provides a model of courageous mercy leadership for today. While it may remain a stretch for us to place organisations in the hands of young women in their early twenties, individuals at all levels of an organisation grow when given opportunities to take responsibility and utilize their prior learning experiences to face new challenges.

When the Bishop of Charleston visited and wanted sisters for his diocese, Catherine recalls her trust in a young woman, writing, “The question was put by his Lordship from the chair who will come to Charleston with me to act as Superior, etc. The only one who came forward offering to fill the office was Sr. Margaret Teresa Dwyer – which afforded great laughing. I had arranged it with her before but did not think she would have courage.[14] What this also demonstrates is the influence of leaders in encouraging others. The simple fact that Catherine, the superior of the congregation, engaged with the woman, a postulant, and gave her responsibility, even if in a small thing, afforded her the courage to act. How can we be leaders who use our influence to encourage others?

It was difficult for Catherine to be faithful to her Catholic tradition. Catholics in Ireland had experienced significant persecution, and in the memoirs written about Catherine after her death, Mary Ann Doyle notes that “she had much to contend with regarding religion, being constantly with Protestants and Quakers.”[15] Catherine faced several challenges in working with some clergy members, such as when Canon Mathias Kelly closed the chapel in Baggot St to the public in 1837 and refused the appointment of a permanent chaplain.[16] Catherine continued to write courteously to Canon Kelly and persisted until they found a solution.

Kingstown

Likewise, in Kingstown, Catherine faced difficulties when Father Bartholomew Sheridan left her to pay the bill for some building work for the parish school. With money not available to pay the invoice, the sisters had no option but to leave the seaside town. While we may perceive withdrawal as a defeat, it was courageous. Catherine was to write to Teresa White saying, “for [God] knows I would rather be cold and hungry than the poor in Kingstown or elsewhere should be deprived of any consolation in our power to afford – but in the present case, we have done all that belonged to us to do – and even more than the circumstances justified.”[17] A woman deeply committed to the Catholic Church, she did not let the actions of individual members diminish her faith. Catholics and Protestants had influenced Catherine’s image of God, and consequently, her vision became more expansive than just that of the Catholic Church.

It took significant courage for Catherine to continue practising Catholicism when it likely would have been easier to be a Protestant. In Catherine, we have a model for courageously practising faith in a society that does not always value religious traditions.

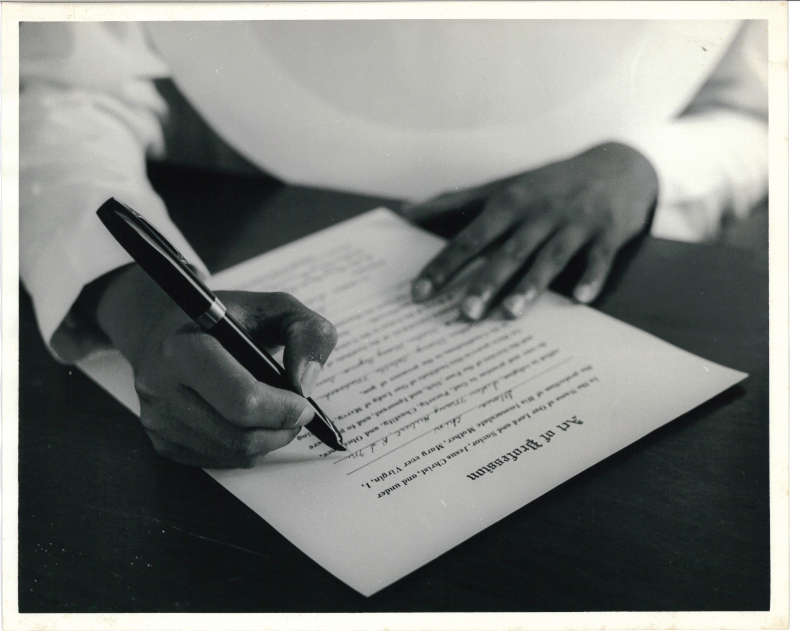

Whilst the examples given refer to courage demonstrated in more significant decisions in the fledgling Mercy community, underlying these actions is a disposition of courage. Catherine’s source of courage was her confidence in God. She was to write to Angela Dunne in 1837, “Put your whole confidence in God,” encouraging trust.[18] She chose a synonymous phrase in a letter to Frances Warde in 1840: “While we place all our confidence in God – we must act as if all depended on our exertion.”[19] In the Spirit of the Institute, Catherine writes again, “We ought then have great confidence in God.”[20]

In her letters, Catherine encouraged the sisters to demonstrate courage. It was to Mary Ann Doyle in Tullamore that she wrote, “Do not fear offending anyone. Speak as your mind directs and always act with more courage when the “mammon of unrighteousness” is in question.”[21] This courage is a particular trait of mercy – standing up to situations of injustice. To be described as courageous, according to Scarre, is to infer an ethical quality, something praiseworthy.[22] Courage is stronger than boldness, and a disposition of reflection is vital for courage to be ethical. Catherine’s prolific letter writing gives insight into her disposition of reflection. The successes that arose from Catherine allowing others to act courageously would have strengthened this disposition.

In summary, mercy courage is not about the violent responses that the etymology of the word in some languages suggests. Instead, courage is an ethical response of the heart that, while responding bravely, does so with compassion. Catherine’s gift was to display courage in her actions to undertake new ventures despite the risk of failure, to respond with compassion to complicated interactions, and to trust others and encourage them, especially through her letters. Catherine knew her strength came from placing her whole confidence in God with lively, unlimited confidence.[23] May we do the same.

Bibliography

Baum, L. Frank. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Minneapolis: Lerner Publishing Group, 2018.

Bourke, Mary C. A Woman Sings of Mercy: Reflections of the Life and Spirit of Mother Catherine McAuley, Foundress of the Sisters of Mercy. Repr. ed. Sydney: Dwyer, 1988.

Carroll, Mary Teresa Austin. Leaves from the Annals of the Sisters of Mercy. Vol. 1: Catholic Publication Society Company, 1884.

Catechism of the Catholic Church. 2 ed. Citta del Vaticano: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2019. https://www.usccb.org/sites/default/files/flipbooks/catechism/.

Harnett, Mary Vincent. “The Limerick Manuscript c.1845-1861.” In Catherine McAuley and the Tradition of Mercy, edited by Mary C. Sullivan. (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1995).

Moore, M. Clare Augustine. “A Memoir of the Foundress of the Sisters of Mercy in Ireland (the Dublin Manuscript) 1864.” In Catherine McAuley and the Tradition of Mercy, edited by Mary C. Sullivan (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1995).

Scarre, Geoffrey. On Courage. London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2010.

Sullivan, Mary C. Catherine McAuley and the Tradition of Mercy. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1995.

Sullivan, Mary C. The Correspondence of Catherine McAuley, 1818-1841. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2004.

Endnotes

[1] Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2 ed. (Citta del Vaticano: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2019), 1808, https://www.usccb.org/sites/default/files/flipbooks/catechism/.

[2] Geoffrey Scarre, On Courage (London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2010), 65.

[3] L. Frank Baum, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Minneapolis: Lerner Publishing Group, 2018).

[4] True Grit, 1969.

[5] No record of Catherine saying this occurs in any of the primary sources, although it is referred to in Mary Teresa Austin Carroll, Leaves from the Annals of the Sisters of Mercy, vol. 1 (Catholic Publication Society Company, 1884), 87.

[6] Now known as Dun Laoghaire

[7] The letter where this is written has not been found, however, it is described in the Tullamore Annals. See footnote 17 in Mary C. Sullivan, The Correspondence of Catherine McAuley, 1818-1841 (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2004), 72.

[8] Carroll, Leaves, 1, 90.

[9] Mary C. Bourke, A Woman Sings of Mercy: Reflections of the Life and Spirit of Mother Catherine McAuley, Foundress of the Sisters of Mercy, Repr. ed. (Sydney: Dwyer, 1988), 38.

[10] Letter of Catherine McAuley to Frances Warde, 17 November 1838, in Sullivan, Correspondence, 168.

[11] Letter of Catherine McAuley to Frances Warde, 25 October 1838, in Correspondence, 159.

[12] Letter of Catherine McAuley to Elizabeth Moore, 9 December 1838 in Correspondence, 169.

[13] Letter of Catherine McAuley to Cecilia Marmion, 15 January 1841 in Correspondence, 347-48.

[14] Letter of Catherine McAuley to Aloysius Scott, 30 June 1841 in Correspondence, 407.

[15] Letter of Mary Ann Doyle to Clare Augustine Moore, 1844 in Catherine McAuley and the Tradition

of Mercy (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1995), 43.

[16] M. Clare Augustine Moore, “A Memoir of the Foundress of the Sisters of Mercy in Ireland (the Dublin Manuscript) 1864,” in Catherine McAuley and the Tradition of Mercy, ed. M. C. Sullivan (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1995), 212.

[17] Letter of Catherine McAuley to Teresa White, 1 November 1838, in Sullivan, Correspondence, 164.

[18] Letter of Catherine McAuley to Angela Dunne, 20 December 1837, in Correspondence, 115.

[19] Letter of Catherine McAuley to Frances Warde, 24 November 1840, in Correspondence, 323.

[20] The Spirit of the Institute by Catherine McAuley, in Correspondence, 462.

[21] Letter of Catherine McAuley to Mary Ann Doyle, 24 July 1841, in Correspondence, 418.

[22] Scarre, On Courage, 31.

[23] See the Suscipe of Catherine McAuley in Mary Vincent Harnett, “The Limerick Manuscript C.1845-1861,” in Catherine McAuley and the Tradition of Mercy, ed. M. C. Sullivan (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1995), 188.