Introduction

From a very young age, Our Lady of Guadalupe is a familiar image for the people of many countries, especially those from Mexico. In Mexico, she is found in almost every home, especially for lower income families. The importance of her apparitions is very well known: she is the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus and our mother; she chose a native man named Juan Diego; she requested a church from the bishop and left her image printed together with the roses that Juan Diego took to the bishop. These facts are the basis of the faith in Our Lady of Guadalupe for many people, although they may not know the name of the official document about the apparitions, the meaning of each one of the elements of the image, her connection to the culture or the problems at the time of the apparitions. Normally, she is venerated and visited close to the anniversary of her apparitions in the month of December. The celebration of Our Lady of Guadalupe in the United States of America began thanks to the faith of the Mexican immigrants who called for the ecclesiastic hierarchy to legitimately include her in churches and in the liturgical calendar.

In most cases the reality of women in Latin American countries as well as in the US continues to be oppression and exploitation by political, cultural and religious systems that are predominantly male. For this reason, as Our Lady of Guadalupe is a feminine image, we have the question of whether this devotion is today giving women the same identity and empowerment that, in its time, it gave the indigenous people, to save their dignity and assert their rights as human beings. Therefore, it is important, as much as possible in this reflection, to delve into the context and theology of the Guadalupan event, questioning the way it is communicated and to what extent it is, or can be, a message of liberation for all people, especially women.

A. Presuppositions

The apparitions and their effects

The apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe to Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin [1] in December of 1531 is an event that caused a shift in the history and faith of the inhabitants of Mexico at the time of the Spanish Colonization. The protagonists were Juan Diego, Our Lady of Guadalupe and Bishop Juan de Zumárraga, a Franciscan. Secondary characters were the men ‘of the house’ of the bishop and Juan Bernardino, the uncle of Juan Diego. All men, only Guadalupe was a woman. The main idea that she presents [2] at first glance is that she is the perfect, ever Virgin Mary, Holy Mother of the True God who gives us life. She asks for a house or temple to show God to the people and to listen, purify [3] and heal. Her apparition happens ten years after the end of the war of conquest, which clearly established who were the conquerors and who were the conquered. The consequence of these apparitions is that all the people that lived in the city, conquerors and conquered, came to recognize the “divine character” [4] of the image.

With her apparition, Guadalupe achieves what none of the missionaries was able to with swords, condemnation and fear. She does not destroy the beliefs of the listeners but rather relies on them and supersedes them. The indigenous found a close relationship between Our Lady of Guadalupe and the goddess, Mother Tonantzin,[5] mother of Ometéotl, the God who is one and also two, in whom is found and integrated every duality, including feminine/masculine. The god who is one and also two reminds us of our Christian faith in Jesus Christ, one person with two natures, as well as one God in three Divine Persons.

Additionally, the place of the apparition, the hill of Tepeyac, or hill of the nose, due to its shape, was where there used to be

“a temple that was the most important and popular center of religiosity in ancient Mexico dedicated to Tonantzin, ‘our venerable mother or our most dignified mother’ […] who also had the name Coatlicue, which means ‘she who carries the serpent on her neck (cuatl is serpent).’ The serpent, for indigenous cultures of Central America, was the symbol of wisdom. The name Coatlicue, can be seen as seat of wisdom.”[6]

The serpent[7] could also “signify a dangerous enemy, as in the legend of the Valley of Anahuac, where the eagle devours the serpent.”[8]. The name Guadalupe, pronounced in Náhuatl, seems to be Coatlaxopeuh, which means “she who crushes the serpent.”[9]. This could be interpreted as Our Lady of Guadalupe is the seat of wisdom who comes to crush whatever denigrates God’s plan for humanity, in accordance with Genesis 3:15 and Revelations 12: 1-17.

Social and Religious Context of the Apparitions in 1531

There was nothing good for the native people at the time of the apparitions. After the conquest, they were reduced by the colonizers to

“humiliating servitude, their women had been violated; their beautiful cities had been burned; and their gods were being destroyed. Their old ways were being discredited, and the new ways did not make sense to them. Nothing of meaning or value was left; there was no reason to live […] the Europeans had brought new diseases that devastated the remaining population, making the stench of death the constant companion of everyday existence.” [10]

The Spaniards forgot their ethical values and established themselves as judges of good and evil, [11] contradicting the preaching of the ‘evangelists.’ The Spanish men used the indigenous women as concubines; they were usually taken against their will and against their customs to be converted into property. They treated the women the same as the land and animals, which they disposed of and rejected. [12]

From the union of the white Spaniards and the dark-skinned native women, comes the mestizo race. [13] This placed those women in the lowest place in society. Their relations with the Spaniards and having children from that union, meant that the women and their children were rejected by their own people as well as by the whites, even though they were their ‘wives’ and children. This is where the word ‘chingada’ meaning ‘one who was raped’ comes from: a woman in a degrading situation through no fault of her own. When she accepted her situation of being taken by the colonizers, she was considered a traitor to her native people. Sadly, in the literature about colonization, women and the resistance that they attempted are rarely mentioned, silencing their voices. The Church was also silent amid these abuses. But in the same way that Jesus of Nazareth was born with features of a dispossessed and oppressed people, Our Lady of Guadalupe presented herself as a mestiza woman, with native symbols in her clothing and European facial features, taking the place of the most denigrated people in that society.

Likewise, the ecclesiastic hierarchy, in the person of Bishop Zumárraga, had destroyed hundreds of temples and thousands of the native peoples’ religious images, thinking that first they had to eliminate what existed to be able to impose a new religiosity.[14] But the request of the Virgin Mary to the bishop, to build her a church where one had been destroyed, is not only referring to a building, but to restoring the religious values and the dignity of non-European people.

Oppressive Marian Interpretations for Women

The devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe has had ambiguous consequences for the value, dignity and liberation of Latina women in their daily life. This devotion to Our Lady[15] is harmful for women when the emphasis is on imitating her maternity, discriminating against those who cannot or do not want to physically conceive. Women are also told to be pure and chaste, mothers who are obedient to their husbands, silent and submissive, completely dedicated to housework and imitating ‘virtues’ with no social commitment. They should accept suffering heroically and passively, as Mary did at the foot of Jesus’ cross. The Church has promoted this model as Mary DeCock demonstrates:

“The Virgin Mary, Mother of God, defined dogmatically in the Church only in relation to her son, is a cultural symbol of uniqueness-indignity, passivity, without sex, a model of abstract purity.”[16]

This mentality toward ‘virtuous’ Christian women has led to a duality of ideas about women. On one side, as a mother, she is the most perfect and close to God. On the other side, women are considered to be the personification of evil that leads men to perdition.[17] This religiosity has fed the machismo that honors the ‘pure’ mother, as if men weren’t conceived through sexual relations. They want their wives to be pure, like Our Lady, before marriage. Afterwards, they must be completely dependent on their husbands, caring for the children and the home, while the men have complete professional and social freedom, as well as being polygamous and mistreating their wives as if they were property.[18]

Reality of Latina Women in the US

Latina women who arrive in the US come from colonized countries. Many of them have not overcome feelings of inferiority, together with the fear of not having legal documents in the United States. This can create a double feeling of being colonized. The low self-esteem grows as they experience abuse from their husbands and in the labor force, as well as discrimination. At the same time, just as colonial times, women in the US are often rejected by friends and family in their home country as traitors who abandoned their home but are also not accepted by the white citizens of the country they inhabit, which means that they suffer any kind of abuse in silence, just to survive. Ada María Isasi-Díaz [19] states that survival of Latina women in the US takes place amid the oppression that comes from domination, subjugation, exploitation and repression, all of which cause them to have a poor self-image as women. This puts Latina women at a severe disadvantage and in the lowest socioeconomic reality and level in US society. It is that society that determines who they are and how they should act as Latinas, according to predetermined frameworks that keep them ignorant, controlled, oppressed and marginalized.

After analyzing the most significant aspects of the Guadalupan apparition, in its context of suffering and loss of identity, as well as the poor interpretations and applications of Marian devotion in the lives of women, I suggest that the devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe needs a liberating re-reading.

B. Our Lady of Guadalupe Liberation for Women

Influence of popular religion in the self-image of women and their liberation

For Latina women, popular religiosity has been a way to understand and express their relationship with God, expressed in the simplest of daily habits. [20] This has given it the title “popular religion,” which is characterized by being non-clerical, sacramental (based on the sacraments), syncretic, inclusive and with its own practices. Popular religiosity has been a means of unique expression of the Latino struggle for liberation, but it is not exempt from errors and misinterpretations, especially regarding women. For this reason, Guadalupan popular religiosity can also be a privileged way to recover the identity and dignity of women, even in very adverse situations. Therefore, it is important to apply the theology of the Gospel for a salvific religiosity.

A Biblical Mariology

B. Reid [21] presents Guadalupe as the model of a woman who integrates being submissive, dependent, timid and hidden with the masculine characteristics of being combative, independent, assertive and a protagonist. Guadalupe has liberating power if she is more than a devotion that many times is alienating, oppressive and disembodied from the reality of actual women. She should be related to the New Testament Marian model, in which Mary acts prudently, with integrity and autonomy (Luke 1:26-45); experiences and sings of the power of God, who lifts up the lowly (Luke 1:46-56); makes her Son act (John 2:1-12); and is supportive until the very last consequences (John 19:25-30). As a mother-disciple, she receives again the gift of the Holy Spirit, equally as the men do on Pentecost (Acts 1:14, 2:1-4).

Guadalupe: feminine expression of God

Although the missionaries who came with the conquerors preached a God of love, forgiveness and mercy, what the conquered people experienced was a god of power, conquest, victory and exploitation. The experience of unconditional love, support, company, and protection was not found in the God announced by men, but rather in Our Lady of Guadalupe, as E. Johnson states:

Mary is the one who “represents the psychologically ultimate validity of the feminine, insuring a religious validation of bodiliness, sensitivity, relationality and nurturing qualities […] The symbol of Mary as feminine principle balances the masculine principle in the deity, which expresses itself in rationality, assertiveness and independence.”[22]

Women feel more confident about talking to Our Lady, because she is a woman and they find greater compassion and response to their requests in her, contrary to the masculine preaching about God of that time. [23] Guadalupe brings forth the ultimate creative power. She shows that it is not through weapons, but by understandable language and symbols like Her that give people healthy pride in a new existence. In this way, each person recovers their legitimacy or legality, based on their dignity of being made in the image and likeness of God, who has been known as Father, but is also Mother. [24] However, J. Rodríguez[25] makes it clear that Our Lady of Guadalupe is not God, but the giving of oneself to God or God’s grace. Grace can be understood as the effects experienced in an interpersonal relationship like helping, hope, affirmation, growth, etc. She is the manifestation of love, compassion, the mercy of God for the poor.

Guadalupe, liberating theophany and place of encounter

The founding experience of salvation of the people of Israel began in the encounter of Moses with God at the burning bush. This encounter was to carry out a mission of transformation for oppressed people. In this way, the people receive an alliance and new dignity and identity as the People of God; a return to the land promised to Abraham and his descendants, and the presence of God in the Tent of Meeting, which became the center and axis of spiritual life and theocratic governance. Surprisingly, the story of the theophany of God in the burning bush and the mission given to Moses has a surprising parallel with what I am daring to call the saving theophany of God in the Guadalupan event and the mission given to Juan Diego.

| Theophany in the burning bush Text: Exodus 3:1-12 | Guadalupan Event Text: Nican Mopohua | ||

| Experience | 3:2-3 on Mount Horeb, the bush burns but is not consumed | #7-22: on the Hill of Tepeyac there is singing, with a dress that shines like the sun, as if it were sending out rays of light | |

| Called by name | 3:4 Moses, Moses | #11: Juan, dearest Juan Diego | |

| Introducing themselves as the divine (making reference to the God of their ancestors) | 3:6 I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob. | #28-31: I have the privilege of being the Mother of the True God, of Ipalnemohuani, (He by whom we live), of Teyocoyani (Creator of people), of Tloque Nahuaque (Lord of the Near and the Nigh), of Ilhuicahua Tlaltipaque (Lord of Heaven and Earth). For I am truly the compassionate mother, to you and to all the people who live together in this land, and to all the people of other ancestries | |

| Liberation | 3:7-8 I have indeed seen the misery of my people in Egypt. I have heard them crying out because of their slave drivers, and I am concerned about their suffering. So, I have come down to rescue them from the hand of the Egyptians and to bring them up out of that land into a good and spacious land, a land flowing with milk and honey. | #32: There I shall listen to their weeping and their sadness, I shall remedy and cleanse and nurse all their various troubles, all their miseries, all their suffering. And to bring about what my compassionate and merciful appearance is trying to accomplish. | |

| Resistance and feeling of incompetence | 3:11 Moses said to God, “Who am I that I should go to Pharaoh and bring the Israelites out of Egypt?” | #54-55: I beg you, my Beloved Lady, to have one of the nobles, one who is held in esteem, one who is known, respected, and honored, have him carry your dear word, so that he will be believed. Because I am really just a man from the country, I am like a mere porter’s rope, a back-frame, a tail, a wing, a man of no importance: I myself need to be led, carried on someone’s back. That place you are sending me to is a place where I’m not used to going to or spending any time in | |

| Firmness and support for sending them | 3:12 And God said, “I will be with you. And this will be the sign to you that it is I who have sent you: When you have brought the people out of Egypt, youwill worship God on this mountain.” | #59-62: But it is very necessary that you personally go and plead, that my wish may become a reality, that it may be carried out through your intercession. I implore you, my youngest-and-dearest son, but I also order you strictly to go again tomorrow to see the bishop. And in my name make him know my will, so that he will bring into being, he will build the house of God that I am asking him for, and carefully tell him again how I, personally, the Ever-Virgin Holy Mary, I, who am the Mother of God, am sending you. | |

| Effects | Liberation from slavery, Alliance-new identity and Tent of Meeting (temple) | Dignity for the natives, new Christian identity, return from the place of encounter: “my sacred house” or temple on Tepeyac | |

There is no doubt that in this parallel we see the action of the one God who has intervened and continues to intervene in our daily life, to save and make known God’s male and female dimensions.

Our Lady of Guadalupe recognizes the identity of the poor

The theophany of Guadalupe[26] is the installation of the Reign of God, which denounces and confronts structures in which God’s plan is not realized. God, through Our Lady of Guadalupe, chooses to be on the side of the dispossessed and exploited. God manifests and is present at the level of the people, communicating through song, flowers, respect for each person, the softness and sweetness of the dialogue, the style of dress, the place,[27] the day and the hour of the apparition,[28] perfectly understandable and on the level of the native people. The confidence and power that this gives to the marginalized and oppressed carries out a prophetic mission: it tears down the wall of division and discrimination so that all human beings have the same dignity in the image and likeness of God,[29]with their being and goal in life in the same God. [30] All this is done without denying the authentic values of the Christian faith, preached by white men, carrying out the Gospel. [31]

Guadalupe takes on the defense of the indigenous in a feminine way,[32] not with arms or defeating the enemy, but rather in a feminine manner, convincing or ‘winning-with,’ integrating the ‘two truths’ in one single truth. In Guadalupe there are no winners, nor losers, but rather all races, peoples and nations[33] together in her compassionate gaze. [34] She goes beyond the Nahuatl deities, manifesting the Christian universalism because it is no longer Tonantzin, or the mother of the gods, but rather the Mother of the inhabitants of this Earth. She also transcends the Marian manifestations that we know of today in the Church and even goes beyond what science can explain about the image of Guadalupe on Juan Diego’s cloak.

Guadalupe asks for a ‘legitimate home’

A home signifies permanence, citizenship and stability. The place where Juan Diego encountered Our Lady of Guadalupe has been as important as the tent of meeting in the Old Testament and its process of configuration and identity as a theocratic people.

However, according to V. Elizondo here there is a greater meaning in accordance with the social context of that place, which requires that the Christian hierarchy of the missionary priests give legitimacy to the children they are ‘begetting’ by the preaching of Christianity and baptism:

“The mother demanding a home for the children of the father is a declaration that the women will no longer remain silent and passive […] With the emergence of the mestizo soul, Juan Diego goes with confidence to call the father to come build a home for the Mother and all their children. The child calls the father to recognize, legitimize and honor the new family that he has started by building a home where the Mother can be honored and venerated and she in turn can show her love and compassion to the entire family. The new home to be built by the father/bishop will be for all their children of the Americas – a common home for all the inhabitants.”[35]

Guadalupe becomes the place of encounter and integration [36] between the masculinity of the Christian faith and the femininity of the Nahuatl faith, where the new identity of a nation begins to grow and be legitimate.

The theology and the implications that Guadalupe brings to life are salvific and liberating for all men and especially for all women, not only for Latina women living in the United States. In Guadalupe there is a clear theophany of the God who recovers and legitimizes the female dimension of God that was already accepted and lived by the first recipients of the apparitions, as well as legitimizes men and women of different races.

C. Practical Consequences for Women

Women who live in the US or other countries where there is racism, discrimination and oppression require a process of liberation that considers the challenges that go along with living in a different country than where they were born.

Liberation of the conscience

To make the liberating message of Guadalupe their own, women need to live according to their own conscience, not that of others. According to Isasi-Diaz,[37] educating morally opens new possibilities of liberation. In this way, Latina women can become conscious of their own value and respect by taking ownership of their own lives and decisions, which affect their integrity as women, their culture and interpersonal relationships. This process of consciousness- raising liberation occurs in every moment and throughout life.

It is essential in the process of liberating the conscience of Latina women in the US that they take back their own identity and choose to be Latina. In this way, they will be able to integrate their diversity without assimilating, comparing destructively or attempting to control. In this way there will be interaction of the ‘different’ with “respect, honesty and risk” [38] where people are recognized for their intrinsic value and power is not wielded for individualistic purposes but in search of the common good. Having a clear identity, women counteract the attitude of those who want to eliminate differences.

Having a clear Latina identity and consciousness of one’s own dignity as a person, means having the challenge of being defined by people with racist prejudice in the US as someone who “has less of everything,” even less importance. On the other hand, the positive is that it makes one become aware of the richness of one’s own country of origin amid the diversity of other cultures. Opting for Latinas, with their mestizo roots is also opting for the poor. It is self-determination, avoiding letting others dominate them as well as liberating themselves from the internalized oppressor, renouncing vengeance in search of the historic, liberating project of the Gospel.

Living mestizaje as Isasi-Díaz also proposes [39] (in the current reality of the US) is a specific way of living the moral of the Guadalupan message. It is denouncing racism, the prejudices among Latinas, the hierarchical mentality that makes women unequal and having the conscience to respond on one’s own behalf “for others and not on behalf of others.”[40] It is appreciation and integration of the diverse cultures, solidarity and reciprocity in all relationships (God, creation, human beings), especially with Latina women, seen as the “other” that they carry within themselves.[41]

Guadalupe: new citizenship

Our Lady appears at sunrise. When, at the end of the night, you can see the sun, the moon and the stars together in the sky, it is the beginning of a new day. Guadalupe carries in her image the sun that is all around her, the stars in her mantle and the moon beneath her feet. Guadalupe is a new sunrise for the value of dark-skinned women who speak a different language than white women. When she asks for a house, or a space to be recognized, where the identity of the diversity of cultures can be established and where God can be revealed through the feminine, Latina women are empowered to reclaim their place in the society of the United States. Having a home would be the revolutionary symbol of citizenship in the world and belonging in the US which, despite being a nation primarily made up of a variety of immigrant races, destroys ‘homes’ or families, dividing them through the deportations of those who seek to live with dignity and recognition of their citizenship.

Flag of liberation and independence

The image in and of itself has been and should continue to be a flag of social justice. The image of Our Lady of Guadalupe was the flag of liberation in 1810 for the mestizos and indigenous of what was then called New Spain in the independence movement against the white Spaniards who oppressed those who were not born in Europe; in 1910 as the standard of the Zapatista revolutionary movement that fought against the injustice toward impoverished farmers, predominantly of darker skin. In the 60s, she was the icon of the movement that fought for justice for farmworkers in the US, led by Cesar Chávez and Dolores Huerta. If Guadalupe has been the icon of liberation directed by men, how much more should she be the icon for the liberation of women because:

“in all of the phenomenon of Our Lady of Guadalupe: her image, the text of the story, the circumstances of her apparition and the later tradition, is synthesized in a history of searching for identity, of needing support, of the possibility of a future.” [42]

D. Conclusion

The apparitions of Our Lady of Guadalupe in a place under foreign domination are the Gospel enculturated in the reality of the American continent and from there, for the whole world. It is a new experience of birth, of resurrection for a new race, whether is mestiza, white or mulatto, and a new Gospel. [43] The mantle of Guadalupe is a type of Holy Shroud [44] for America and the world, showing that where there was death, now there is proof that God is alive and hears the cry of the poor, saving them from the depths of the abyss and giving life where all hope was lost. From all perspectives, the Guadalupan message is life, inculturation, unity of races, option for the poor and liberation.

There is much to do regarding the theological and social message of Guadalupe. Most women devoted to Guadalupe go to her as a mother and protector, but they know little of her enculturated and liberating significance. We need to assume the practical consequences of the Guadalupan message to help liberate the ‘indoctrinated’ consciences that are generally promoted by men so that Latina women can find themselves in Guadalupe. In this way, they will be women fully capable of being mestizas, in a land of white women, with the right to hold space where they can feel accepted, welcome and have a place to belong. Latina women capable of lifting their own voices and demonstrating with pride their dignity as daughters of God to offer dignity and justice for themselves, and for the men and women of all races, languages and nations.[45]

YES! THE DEVOTION TO OUR LADY OF GUADALUPE CAN BE

LIBERATION FOR WOMEN!

LONG LIVE OUR LADY OF GUADALUPE!

[1] “Cuauhtlatoatzin” is Juan Diego’s name before being baptized and means, in the Náhuatl language “he who speaks like an eagle” or “eagle that speaks”. Cf. “San Juan Diego, Un Modelo de Humildad” Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. http://www.sancta.org/juandiego_s.html. (Accessed 11-21-11). Which is an interesting contrast with the name of the last Mexica emperor, Cuauhtémoc, which means “Eagle that falls” or comes down.

[2] Cf. Nican Mopohua (Spanish) Translation and commentary by Mons. José Luis Guerrero Rosado. http://virgendeguadalupepatronadeamerica.blogspot.com/2009/11/nican-mopohua-el-relato.html (Accessed 11-3-2011).

[3] Fr. Mario Rojas Gonzales translates “purify” for remedy. Cf Nican Mopohua (Spanish) Version by Fr. Mario Rojas in the book “Huei tlamahuiçoltica…”, by Luis Laso de la Vega, 1649. http://www.proyectoguadalupe.com/documentos/t_c_nican.html

[4] Guerrero. Nican Mopohua.215

[5] “Before the arrival of the Spanish, the Aztec people, whose language was Nahuatl, adored Ometeotl, the one true god. His name means “ ‘God Two’ a strange title for us, and even more if we consider its complete form, Ometecuhtli-Omecihuatl: ‘God and Goddess of Duality, […] the Indian sensitivity, deeply in tune with the duality-unity that surrounds us, like male-female, life-death, light-darkness, air-earth, etc.”. Guerrero, José Luis, Flor y Canto del nacimiento de México” México, 1990. Pg. 235. Quoted in, Porcile Santiso, Teresa “Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. Modelo de evangelización en una cultura” Con ojos de mujer. Ediciones Doble Clic. Uruguay.1997. Pg. 208

[6] Porcile Santiso, Con ojos de mujer. 211

[7] The same happens in the Biblical tradition with respect to the serpent in Genesis 3 and particularly the dualism of the meaning of the serpent bad-good shown in Numbers 21:6-8

[8] Porcile Santiso, Con ojos de mujer. 202

[9] Cf. Guadalupe. http://www.sancta.org/nameguad.htm

[10] Elizondo, Virgil. Guadalupe, Mother of the New Creation. Orbis, NY. 1997. Pg. 26

[11] Cf. Genesis 3:5

[12] Aquino, Pilar, Our Cry for Life. Orbis.NY.1993. pg. 46-47

[13] “ «… mestizaje was enthusiastically accepted and promoted by the Indians, who happily handed over their daughters and sisters, but never expected the shame when, upon the birth of children from these unions, the parents abandoned them and considered the mothers shameful for doing so…»* As a consequence of the above, many children were rejected by both parents and became orphans, living in poverty; and She, precisely, assumed the color of those abandoned and humiliated children.”http://www.virgendeguadalupe.org.mx/sugerencias/gpe_viva.htm * Guerrero Rosado, El Nican Mopohua, t. I, p. 456. The Indian society, whose male population was decreased due to wars or their dedication to the priesthood, could see clearly that the nobles took many women for their wives. This “…wasn’t widely permitted, as some think, but only for those who were considered to be of high quality and esteem, people of value, and they could not have more wives than they could provide food and clothing for…” In Durán, History of the Indies, t. l, Chapter X, pg. 264. It is because of this that the “…Indians and even the Indian women, at the beginning happily favored the polygamy of the white men, because they considered it completely in line with their traditions, but as a people who loved their children and were quite disciplined and ascetic in their sexual relations, they were not prepared for the scandal of seeing them later reject their ‘wives’ and even worse, not care for their own children, without ignoring the precepts of their religion. For the Indians, this was […] committing the unspeakable disgrace of rejecting and abandoning their wives and children…” In Guerrero Rosado, Nican Mopohua, t. I, pg. 53.

[14] Cf. Elizondo, Guadalupe, Mother of the New Creation. 55

[15] Cf. Gonzalez, Michelle A. Embracing Latina Spirituality. A woman’s perspective. St Anthony Messenger press. OH.2009. 50-51; Birgemer, Maria Clara, “Women in the future of the Theology of liberation” in Feminist theology from the Third World. King, Ursula ed. SPCK/Orbis Press. 1994. 313

[16] DeCock, Mary, BVM “Our Lady of Guadalupe: Symbol of Liberation? in Mary according to Women. Jegen, Carol Frances BVM Ed. Leaven Press. Kansas City, MO 1985. 121

[17] Cf. Aquino, Maria Pilar. Our Cry for life. Feminist theology from Latin America. Orbis. N.Y 1993.14-15. DeCock, Mary, BVM “Our Lady of Guadalupe: Symbol of Liberation? in Mary according to Women. Jegen, Carol Frances Ed. Leaven Press. Kansas City, MO. 1985.120.

[18] Cf. Ibid.

[19] Cf. Isasi-Díaz, Ada María. En la Lucha. In the Struggle. Elaborating a Mujerista Theology. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1993. 30-51

[20] Cf Isasi-Díaz, Ada María. “Popular religiosity as an element of mujerista theology”, In the Struggle. Elaborating a Mujerista Theology. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1993. (61-66) 74-76

[21] Reid, Barbara OP, Taking up the Cross: New Testament Interpretations through Latina and Feminist Eyes. EVD. Navarra, España,2009. 293-296

[22] Johnson, Elizabeth, 1989: 517 Cited in Rodríguez, Jeanette “Guadalupe: The Feminine Face of God” in Ana Castillo ED. Goddess of the Americas: writings on the Virgin of Guadalupe. Riverhead Books. N.Y. 1996. 28

[23]Cf. Rodríguez, Jeanette “Guadalupe: The Feminine Face of God” in Ana Castillo ED. Goddess of the Americas: writings on the Virgin of Guadalupe. Riverhead Books. N.Y. 1996.29

[24] Cf. Rodriguez, J and Fortier,T. Cultural Memory. Resistance, Faith and identity. 27-28

[25] Cf. Rodríguez, Jeanette “Guadalupe: The Feminine Face of God” Goddess. 29

[26] Gevara & M. Bingemer. Mary Mother of God, Mother of the poor. Orbis. New York. 1989 144-154

[27] Tepeyac, or nose mountain where the temple to the goddess Tonantzin was located

[28] At the Winter solstice of 1531.

[29] Genesis 1:26-27

[30] Cf. Ephesians 2:14-15.

[31] Cf. Matthew 5:17

[32] “The method of Guadalupe is based on beauty, recognition and respect for ‘the other,’ and friendly dialogue. It is based on the power of attraction, not on threats of any kind. Juan Diego is attracted by the beautiful singing that he hears; he is fascinated by the gentleness and friendliness of the Lady, who by her appearance is evidently an important person; he is uplifted by her respectful and tender treatment of him; he is captivated by her looks […]in her presence Juan Diego exhibits no inferiority or fears. Here there is no fear of hell – here, Juan Diego is experiencing heaven.” She is like Jesus, who attracts the vulnerable, the scorned and the impoverished, those with no hope and marginalized, not by criticizing and looking down on their religious practices or threatening them with hell. Elizondo, Virgil. Guadalupe, Mother of the New Creation. Orbis, NY. 1997.122

[33] Cf. Revelation.5:9

[34] In studies of her eyes, experts have found the reflection of people with white, native and black features. Cf. Hernandez, Ana. Science and Guadalupe Virgin. web.mac.com/…Guadalupe…/science_guadalupe_virgin.doc. Accessed 11-20-2011

[35] Elizondo, V, Guadalupe, Mother of the New Creation. 111

[36] “The male Father God of militaristic and patriarchal Christianity is united to the female Mother God (Tonantzin) which allows the original heart and face of Christianity to shine forth: compassion, understanding, tenderness and healing. The harsh and punishing ‘God of justice’ of the West is tempered with the listening and healing ‘companion,’ while the all-powerful and conquering God is transformed into a loving and caring Parent. The distant God of dogmatic formula is dissolved into a friendly and intimate presence. At the same time, the distant, faceless and complicated gods of the Nahuatls are assumed into the very human though divine person of Our Lady of Guadalupe.” Elizondo, V, Guadalupe, Mother of the New Creation. 126

[37] Cf. Isasi-Díaz, Ada María. En la Lucha. In the Struggle. Elaborating a Mujerista Theology. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1993. 209-210

[38] Ibid. 207

[39] Ibid. 210-212

[40] Ibid. 211

[41] Cf. Ibid. 212

[42] Navia Velasco, Carmiña. La mujer en la Biblia: opresión y liberación.

http://www.vi.cl/foro/topic/5582-la-mujer-en-la-bibliaopresion-y-liberacion-desde-la-pag-4/page__st__60

[43] Cf. Matthew 9:17

[44] Only on the Holy Shroud of Turin and Juan Diego’s cloak are there images that defy scientific explanation.

[45] Cf. Revelation 5:9

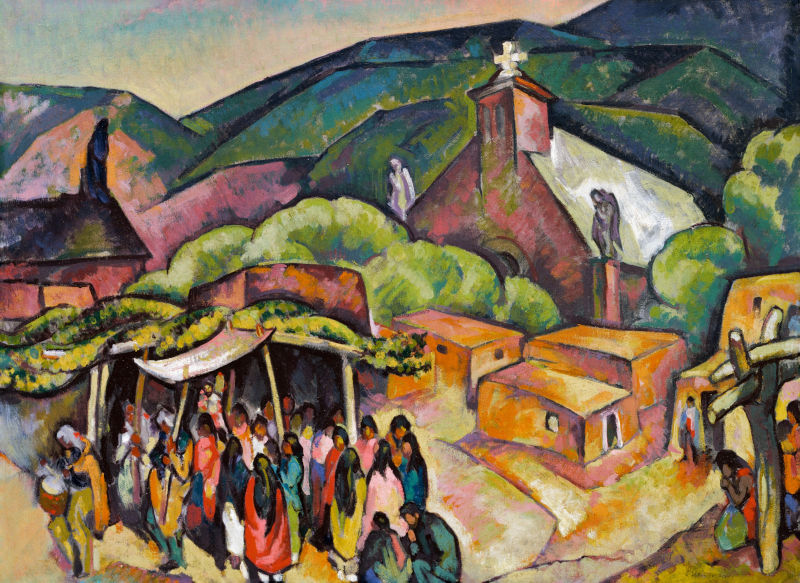

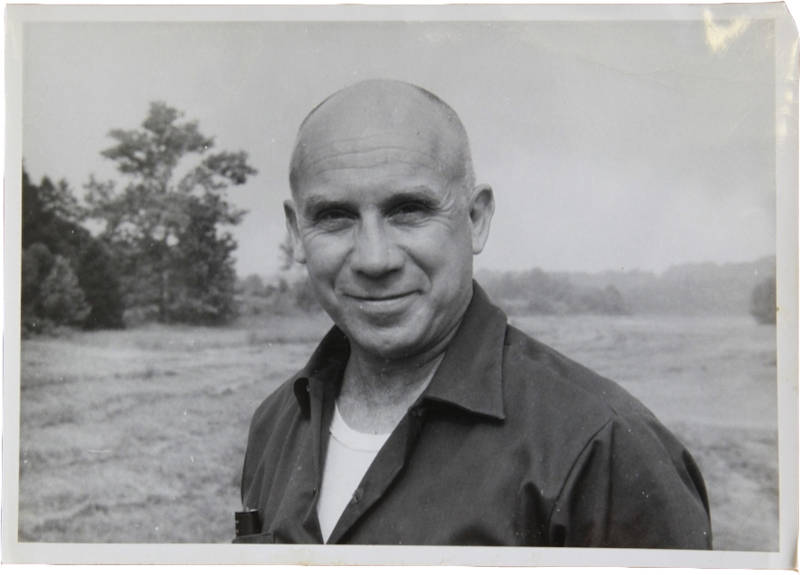

image: Mural of Our Lady of Guadalupe

across from the San Ysleta Mission in El Paso, Texas