In this essay I wish to explore Catherine McAuley’s concepts of comforting and animating, by which I believe she defined both her own unique contribution to the founding of the Sisters of Mercy, and two essential works of those who would personally quicken the re-founding of the mission of the Sisters of Mercy in this and the next century. To “comfort” and to “animate” are among the most frequently used words in Catherine’s personal vocabulary. They are outgoing, life-giving and life-sustaining verbs which represent for her both the merciful action of God in our regard and two aspects of the merciful response which God asks of us in Christ Jesus.

Catherine’s characteristic attraction to these verbs (and their noun and adjectival forms) is an important linguistic clue to her operative definition of mercifulness, and to the simplicity of her self-understanding as a “founder.”[1] These words, which she so often uses, not only give insight into her implicit Christology, pneumatology, and ecclesiology; they also define central endeavors in what she would regard as the fundamental Gospel project of members and associates of the Sisters of Mercy.

Comforting the Afflicted

In her letter of August 28, 1844, Clare Moore, one of Catherine’s earliest associates, tells the moving story about Catherine and Mary Ann Redmond:

In July [1830] before Revd. Mother went to George’s Hill, she was sent by Dr. [Michael] Blake to attend a young lady with white swelling in her knee. Her father and mother were dead, and she had no one with her, but a young inexperienced cousin and an old country nurse. Her name was Mary Ann Redmond, she was from Waterford or Cork. The first physicians were attending her and they judged it necessary to amputate the limb. Dr. Blake requested Revd. Mother to allow her to be in Baggot St. for the operation, as she was so friendless, and alone, in lodgings. Revd. Mother’s charity readily consented, she was accommodated with the large room which is now divided into Noviceship and Infirmary. Mother Mary Ann [Doyle] and Sr. Mary Angela [Dunne] were present at the operation; her screams were frightful, we attended her night and day, for more than a month, at the end of which time she was removed a little way into the country.

Of this event the Bermondsey Annals says: “Miss McAuley offered her a home in Baggot Street that she might be able to assist and comfort her under this terrible operation, which was performed there, tho’ without any beneficial result. During the month that the young person was in the convent, she watched over her night and day with the solicitude of a parent….”[2]

This brief narrative of Catherine McAuley’s comforting Mary Ann Redmond, watching over her night and day with the solicitude of a parent, is a revealing token of Catherine’s character: a luminous story through which one can enter other stories of the larger narrative of her life and begin to plumb the precise quality of her mercifulness. For Catherine’s life was, in large measure, what she understood every Christian life-narrative should be: a re-enactment, in a new time and place, of the continuing story of God’s comforting self-bestowal in human history—in, with, and for the poor and suffering.

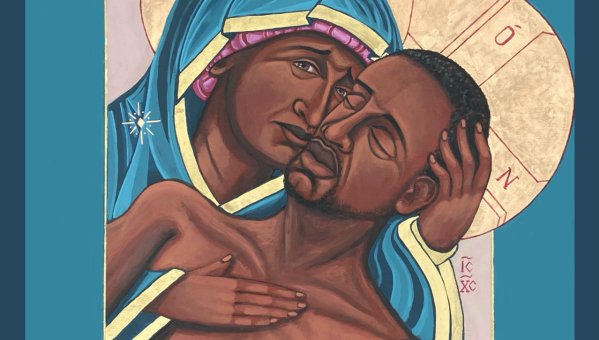

If one studies Catherine’s life and reflects carefully on her written words and on the memoirs of her earliest associates, it is not hard to find the archetypal story of God’s mercifulness in the light of which Catherine read and shaped her own life. That story is the example of Jesus of Nazareth, and the invitation to follow him which he makes explicit in his self-identification with the poor: “Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers and sisters, you did it to me” (Matthew 25:40). In the most serious and deliberate words Catherine ever wrote—the sections of the Rule of the Sisters of Mercy which she herself composed—she repeatedly expressed this fundamental conviction of her life:

In undertaking the arduous, but very meritorious duty of instructing the Poor, the Sisters whom God has graciously pleased to call to this state…shall animate their zeal and fervor by the example of … Jesus Christ, who testified on all occasions a tender love for the poor and declared that he would consider as done to Himself whatever should be done unto them. (1.2)[3]

She urged her sisters to remember that:

Mercy, the principal path pointed out by Jesus Christ to those who are desirous of following Him, has in all ages of the Church excited the faithful in a particular manner to instruct and comfort the sick and dying Poor—as in them they regarded the person of our Divine Master who has said: “Amen, I say to you, as long as you did it to one of these my least brethren, you did it to Me.” (3.1)

This was Catherine McAuley’s understanding of the essence of Christian mercifulness: deep interior and exterior resemblance to Jesus Christ and merciful solidarity with him in the person of the poor and needy, in their habitations and in her own. The rooms of her house, her tables and chairs, her beds and food, her body and spirit, her arms and legs, her health and sickness were for “the care of His most dear poor” (388).[4] And it was this kind of ardent self-bestowal that she looked for in the first Sisters of Mercy.

The Derry Large Manuscript, in its present form, begins with the claim that even before the death of William Callaghan, Catherine took:

great delight in projecting means of affording shelter to unprotected young women. She had then no expectation of the large fortune that afterwards was hers, but her benefactor had once spoken of leaving her a thousand pounds, and she thought, if she had that, or even a few hundred, she would hire a couple of rooms and work for and with her protegees. The idea haunted her very dreams. Night after night she would see herself in some very large place where a number of young women were employed as laundresses or at plainwork, while she herself would be surrounded by a crowd of ragged children which she was washing and dressing very busily. The premises [on Baggot Street] therefore were planned to contain dormitories for young women who for want of proper protection might be exposed to danger, a female poor school, — and apartments for ladies who might choose, for any definite or indefinite time, to devote themselves to the service of the poor.

The House on Baggot Street became, in a variety of practical, merciful ways, a place of refuge, protection, training, and comfort for dozens of orphaned, homeless, and distressed young women and children. According to Clare Moore’s letter of August 26, 1845, “Little Mary Quinn [an orphan] used to sit [at table] between Revd. Mother and Mother Francis Warde.” During the 1832 cholera epidemic at least one baby was brought home in Catherine’s shawl. Again, it is Clare Moore who tells the story of their nursing the sick and dying cholera victims:

We went early in the morning, four sisters, who were relieved by four others in two or three hours, and so on till 8 o’ c in the evening. Revd. Mother was there very much. She used to go in Kirwan’s car, and once a poor woman being either lately or at the time confined and died just after of cholera, dear Revd. Mother had such compassion on the infant that she brought it home under her shawl and put it to sleep in a little bed in her own cell, but as you may guess the little thing cried all night, Revd. Mother could get no rest, so the next day it was given to someone to take care of it.

Catherine seems to have put herself in the position of those who suffer and to have felt their suffering as her own. In November 1840 she wrote in sorrow to Catherine Meagher in Naas about the widespread unemployment in Dublin and her inability to house a young woman sent to Baggot Street for shelter:

I...regret exceedingly that it is impossible to admit the young person. We are always crowded to excess [50-60 in the House of Mercy] at this season—so many leaving Dublin, dismissing servants and few engaging any. We have every day most sorrowful applications from interesting young creatures, confectioners and dressmakers, who, at this season, cannot get employment, and are quite unprotected.

I am sure I spoke with two yesterday who were hungry, tho’ of nice appearance. Their dejected faces have been before me ever since. I was afraid of hurting their feelings by offering them food and had no money (255-6).

To name the merciful work of Catherine McAuley even more precisely it is useful to study her characteristic vocabulary, the words she repeatedly used to express her purposes, values, and desires. The editorial choices she made in transcribing and composing the Rule and Constitutions of the Sisters of Mercy are an especially fruitful source for such insight, as are the key words in her letters and other writings. Moreover, since her personal vocabulary indirectly influenced the wording of the early eyewitness accounts of her life, the particular words her associates repeatedly used as they reminisced about her also provide distinct insights into Catherine’s mercifulness.

Of special significance in identifying the mercifulness which was central to her character and behavior is her repeated and somewhat interchangeable use of the words “comfort” and “console.” In the extant letters she wrote to her sisters from early 1837 on, after the first foundation outside of Dublin, she frequently used these words to refer to the comfort she herself felt or desired, the comfort she wished to give others, and, especially, the comfort which God gives. “Comfort” is, I believe, Catherine’s distinctive way of naming both the effect of actively merciful relations and work, and the profound mercifulness of God which she believed inspires and makes possible all genuine human comforting.[5]

For example, in her letters Catherine says that she could speak with James Maher (Carlow) “with all the confidence of one addressing a long well-proven friend, and such comfort does not often fall to my lot” (116-17); she anticipates the “comfort” the completed laundry will give her, in then being able to provide for the poor women in the House of Mercy (122); she notes that Andrew Fitzgerald (Carlow College) “gave me great comfort, for while he condemned the proceeding [in the Kingstown controversy], he reasoned with me so as to produce quiet of mind and heart” (125); and she admits to Frances Warde, “what a comfort it would be to have you once more one of the number” at Baggot Street (170).[6]

From Birr she writes, “We have two great comforts here, excellent bread in the Dublin household form, and pure sparkling spring water” (292); “what a comfort it gives [her] to hear of [Mary Teresa White’s] continued happiness” (303); she is “greatly comforted to find all in Birr going on so well” (315); “it comforts [her] more than [she] can express to find [the novices] so initiated in the real spirit of their state” (326-7); and she is “comforted to hear that [Frances Warde’s] seeming great cross is not so heavy as was apprehended” (342).

In all these instances, and others, Catherine is speaking of the human comfort which compassion and presence confer, of the solicitude which reaches out to share another’s need or sorrow, and of simple human ways of standing in comforting solidarity with others. Implicit in nearly all of these instances is her personal comfort when the well-being of others is assured.

Because Catherine herself knew the pain of “sorrow,” “humiliation,” “perplexity,” “bitter-sweets,” “dread,” “anguish,” and even “bitterness,” as her letters attest, she knew what comfort, consolation, and tender affection could mean to those who suffer—whether the poor, the sick and dying, or her own young sisters. She was, therefore, eager to give human comfort to others in their affliction and to assure them of the comfort God would give. She believed that “their Heavenly Father will provide comfort for [the poor of Kingstown]” (142); she assured Frances Warde that “God will send some distinguished consolation” to her in her personal affliction (341); she urged the sisters loaned from Dublin to comfort Clare Moore when typhoid fever struck the London foundation (311); and of the poor of Charleville she wrote, “my heart felt sorrowful when I thought of the poor being deprived of the comfort which God seemed to intend for them” (138).

One of the most tender expressions of Catherine’s desire to comfort is her March 21, 1840 letter to Elizabeth Moore, on the death of Mary Teresa Vincent (Ellen) Potter, a young professed sister in the Limerick community:

I did not think any event in this world could make me feel so much. I have cried heartily and implored God to comfort you. I know He will…. My heart is sore, not on my account nor for the sweet innocent spirit that has returned to her Heavenly Father’s Bosom, but for you. You may be sure I will go see you, if it were much more out of the way, and indeed I will greatly feel the loss that will be visible on entering the Convent. Earnestly and humbly praying God to grant you His Divine consolation, and to comfort and bless all the dear Sisters, I remain, Your ever most affectionate M. C. McAuley (204).

The accounts written by Catherine’s earliest associates tell numerous stories of her comforting the afflicted—of her efforts to give strength and hope, to ease grief, to lift spirits, to impart encouragement and cheer, to alter afflictive situations, and to provide safety and protection. For example, the Bermondsey Annals entry for 1841, which preserves Clare Moore’s recollections, speaks of Catherine’s rising in the early morning and “selecting, and transcribing from pious books, certain passages which might be useful for the instruction or consolation of the sick poor.” The Annals also notes that “Her compassion led her to make the greatest sacrifices in favour of the suffering and afflicted.” For example, during the cholera epidemic, “she might be seen among the dead and dying, praying by the bedside of the agonized Christian, inspiring him with sentiments of contrition for his sins, suggesting acts of resignation, hope and confidence, and elevating his heart to God by charity.”

Catherine’s concept of comfort and consolation was clearly biblical, and intimately related to her theology of God’s Mercy and to her Christology. For her, the comfort or consolation of God was the God-given realization that human lives are, despite all affliction and apparent devastation, finally sustained and redeemed by the merciful care of God manifested in Jesus Christ and in the action of those who follow him. Catherine therefore made her own the prophetic task announced by Deutero-Isaiah and irrevocably fulfilled in Jesus: “Comfort, comfort my people, says your God; speak tenderly to Jerusalem and cry to her, that her time of service is ended, that her iniquity is pardoned, that she has received from Yahweh’s hand double for all her sins” (Isaiah 40:1-2).

In the faces of cholera victims, destitute young girls, the dying poor, homeless unemployed women, and her own sick and dying companions, she came to know, as had Saint Paul, “the God of mercies and God of all comfort, who comforts us in all our affliction, so that we may be able to comfort those who are in any affliction, with the comfort with which we ourselves are comforted by God” (2 Corinthians 1:3-4).

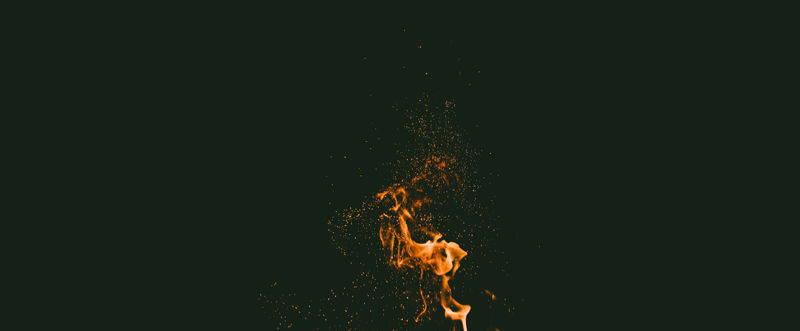

Catherine McAuley wished to be a paraclete, an advocate, a comforter. Though she was not a systematic theologian, aspects of what must have been her operative theology of participation in the work of the Spirit of God are evident, in fragmentary ways, throughout her writings. On a fly-leaf of her Journal of Meditations she had written a “Prayer Before Meditation” which begins: “Come Holy Ghost, take possession of our hearts and kindle in them the fire of thy divine love.” For Catherine, this fire, which she says “Christ cast,” is vibrantly active love of God and of one’s neighbor, modeled on the practice of Jesus, and inspired and sustained by the Spirit of God.

As W. E. Vine’s Expository Dictionary of New Testament Words points out, parakletos, meaning literally, “called to one’s side,” was “used in a court of justice to denote a legal assistant, counsel for the defense, an advocate; then, generally, one who pleads another’s cause…. In the widest sense, it signifies a succourer, comforter” (200). Jesus was such a counselor and he promised “another Counselor” (John 14:16), the Spirit of Truth assured to his disciples in John 14:26, 15:26, and 16:7. I believe Catherine McAuley knew, at her own “side,” the power and presence of this Spirit, and that she therefore knew herself explicitly called to be the human voice, hands, and feet of this comforting Counselor, literally, at the side and in the defense of the poor and afflicted.[7]

In an important set of letters written during Catherine’s last illness, Mary Vincent Whitty, then twenty-two years old, records Catherine’s last use of the word “comfort.” Writing to Mary Cecilia Marmion in Birmingham, on November 12, 1841, the day after Catherine’s death, Mary Vincent relates a scene at Catherine’s bedside the day before:

She told Sr. Teresa [Carton], now fearing I might forget it again, will you tell the Srs. to get a good cup of tea—I think the Community room would be a good place—when I am gone and to comfort one another—but God will comfort them—she said to me, if you give yourself entirely to God—all you have to serve him, every power of your mind and heart—you will have a consolation you will not know where it comes from.[8]

In this, her final human act of comforting, the merciful character of Catherine McAuley is displayed with remarkable simplicity and homeliness. The same practical alertness to others’ needs that had marked her entire life, the same life-long recognition that human beings must actively comfort one another, and the same abiding conviction that, finally, all comfort comes from God are here concentrated in a “cup of tea” for those who grieve.

Animating the Human Spirit

The outstanding feature of Catherine McAuley’s behavior precisely as a founder was not that she was outstanding, though she was. Rather it was her animation of the zeal of her companions. Her collaborative, supportive mode of ecclesial leadership was, in many important respects, a new and feminine model of ecclesial administration. She was willing to work with and defer to what her associates brought to their common efforts, even when their talents or knowledge or courage might have seemed less than what was needed at the moment; she was willing to learn from them and with them as the decade unfolded; she suffered with them and took her place at their side, in poverty, uncertainty, sickness, and death; and she made herself, gradually and finally, completely dispensable to their work and to their future. In all this, her one unique and irreplaceable contribution as their founder was to animate them-that is, continually to remind them of the true spirit of what they were about, and to kindle, by every human means in her power, the God-given life and desire that was already in them.

Catherine wrote often about the “true spirit” of the order, the quintessential spirit of their common religious project. For her this vital spirit was the love of God, the fundamental life-reality which gave strength and purpose to all the human particulars of their life and work. Its source was God’s merciful blessing; its two external manifestations were their own union and charity and their mercifulness toward others. Writing at Easter in 1841 to her close friend Elizabeth Moore, Catherine rejoiced in the spirit of the young women who were preparing for reception of the habit and profession of vows at Baggot Street

All are good and happy. The blessing of unity still dwells amongst us and oh what a blessing, it should make all things else pass into nothing. All laugh and play together, not one cold, stiff soul appears. From the day they enter, all reserve of any ungracious kind leaves them. This is the spirit of the Order, indeed the true spirit of Mercy flowing on us…. (330-31)

Catherine believed that this warm, free, gracious spirit was of divine origin. It was God’s own animating gift to the community and to those they served, if they would but yield to it, treasure it, and act upon it. It was, she believed, “some of the fire [Christ] cast on the earth—kindling” (226). Catherine refers twice to this verse in Luke’s Gospel (12:49) when describing the young English women preparing for the foundation in Birmingham:

They are all that is promising—every mark of real solid vocation—most edifying at all times, at recreation the gayest of the gay. They seem so far to have corresponded very faithfully with the graces received as each day there appears increased fervour and animation…. They renew my poor spirit greatly—five creatures fit to adorn society coming forward joyfully to consecrate themselves to the service of the poor for Christ’s sake. This is some of the fire He cast on the earth—kindling. (226)

Catherine believed that the true spirit of the Sisters of Mercy was the animation given to their human spirits by God’s own Spirit, the Spirit of Christ. Consequently, she believed that her unique obligation as their founder was to support and nurture this animation. Every lecture she gave, every journey she took, and every letter she wrote to her sisters was to encourage and sustain this animation. Thus in October 1837, for example—two months after the death of her niece Catherine and while Mary de Chantal McCann lay dying in Kingstown—Catherine wrote from Cork to Frances Warde, who was herself grieving the death of her bishop a week before: “I will return by Carlow to see you, if only for a few hours …. May God bless and animate you with His own divine spirit that you may prove it is Jesus Christ you love and serve with your whole heart” (101-2).

Just as “comfort” or “console” was a characteristic word in Catherine’s personal vocabulary, so was “animate,” the verb and its adjectival and noun forms. “Animation” was the word Catherine repeatedly used to designate the effect of God’s merciful action in human hearts and the power of Jesus’ example. To be animated by the Spirit of Christ was to manifest all the God-given and humanly sustained liveliness of the true spirit of the order: the spirit of mutual love and service of the poor.

Thus she urged Frances Warde, even in her sorrow, to be “cheerful and happy, animating all around you” (118); and she told Elizabeth Moore, “I ought to say all that could animate and comfort you, for you are a credit and a comfort to me” (167). On the eve of their departure for Bermondsey, she found Clare Moore “all animation” (177); and she imagined “what renewed animation and strength” the return of sisters would bring to “poor old” Baggot Street (234). She treasured the newcomer Frances Gibson, “a sweet docile animated creature, all alive and delighted with her duties” (354); she believed that each return visit to a new foundation “animates the new beginners, and gives confidence to others” (331); and, about six weeks before her death, she urged Juliana Hardman, the young superior of Birmingham, to “pray fervently for those animating graces which will lead us on in uniform peace, making the yoke of our Dear Redeemer easy” (379).

Catherine had, it must be admitted, a natural preference for out-going warmth, swift action, and liveliness. She complained that Clare Augustine Moore, an artist, was too slow-moving, having taken all day to paint “3 rose or lily leaves” (312); she worried that a prospective postulant, a former Carmelite, “is not half alive” and “If it is arranged, I shall have a nice task opening the [downcast] eyes of the little Carmelite” (312); and she once wished that the Tullamore community were not “such creep-mouses” about starting new foundations.

But the animation which she particularly sought and prayed for was a much deeper reality: the vivacious generosity of spirit made possible by the Spirit of God, giving her companions an “ardent desire to understand perfectly the obligations of religious life and to enter into the real spirit of their state” (319). While Catherine understood that all her associates were responsible, before God, for nurturing and encouraging the continuation of this God-given “animation,” she seems to have recognized that she personally had a special and explicit obligation to exemplify and promote this first quickening, by her own zeal. She was the “founder” of the Sisters of Mercy precisely in this vivifying sense: she recognized and named the animating gift of God; she continually gave life, spirit, and support to the fruit of that gift; she used every opportunity to cheer and invigorate her sisters; and she deliberately nurtured their God-given charity and zeal. In a word, she animated them—by her words, her example, her presence, her affection, and her own concrete commitment to the works of mercy.

Although Clare Augustine Moore claims: “I cannot say that our dear foundress had a talent for education; she doted on children and invariably spoiled them,” all the eye-witness accounts of Catherine’s first associates suggest that she was a very effective teacher of the women who were her companions. It is remarkable how precisely they remember and treasure her “sayings” and instructions. Catherine was convinced that “we learn more by example than by precept,” but she also had a keen sense of the animating value of inspiring verbal instruction. She seems to have regarded the oral instructions she regularly gave to the community, especially to the novices, and the public spiritual reading which she chose for them as very important means of animating the spirit that was already alive within them.

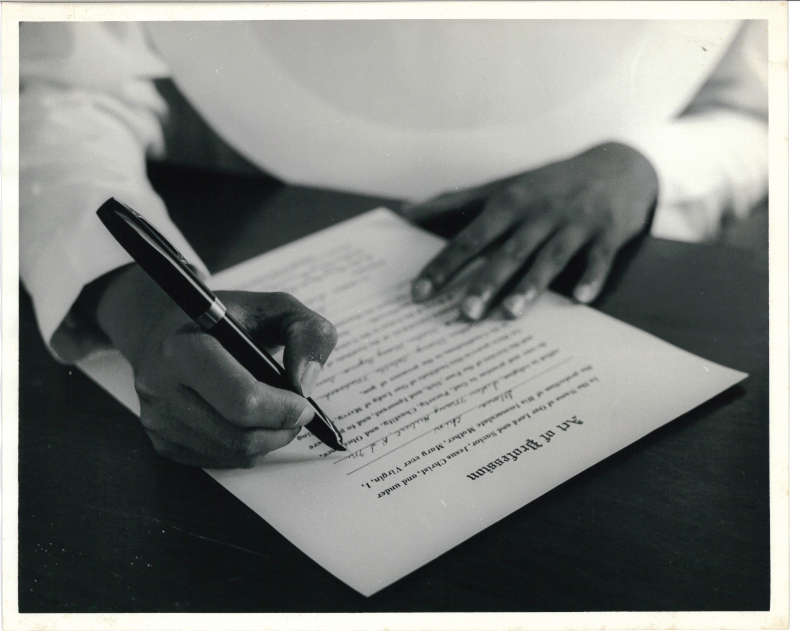

Therefore the daily schedule of the Baggot Street community included a period of time in the morning for “Lecture,” before the day’s work began. At this time Catherine gave formal spiritual instructions to the community, either by reading from a book of her choice, by reading from a transcription they had made, or simply by speaking directly to them, with or without notes. In addition, she gave regular instruction to all the postulants and novices during the four years (1831-1835) when she retained for herself the role of Mistress of Novices, and she personally guided their daily meditations during their retreats prior to reception and profession. Although she usually tried to arrange for a priest to be the resident director for the community’s annual August retreat, on at least one occasion Catherine herself gave this retreat. In a letter to Frances Warde in early August 1841, she wryly refers to her upcoming role: “‘Father’ McAuley conducts the retreat in poor Baggot St” (360).

As the Bermondsey Annals reports, Catherine’s themes for these instructions were those which animated her own spirit, the great themes of the Gospel derived from Jesus’ own life and instructions:

Her exhortations were most animating and impressive especially on the duties of humility and charity. These were her characteristic virtues, and on St. Paul’s description of charity she loved to expatiate, most earnestly striving to reduce it to practise herself, and to induce all under her charge to do the same. She loved all and sought to do good to all, but the poor and little children were her special favourites; these she laboured to instruct, relieve and console in every possible way. She taught the Sisters to avoid all that might be in the least contrary to charity, even the slightest remark on manner, natural defects, etc. so that they should make it a rule never to say anything unfavourable of each other. She was not content with their avoiding the smallest faults against this favourite virtue of our Blessed Lord, she wished their whole conduct should evince that this virtue reigned in their hearts…. Her lessons on charity and humility being supported by her own unvarying example necessarily made a deep impression on the minds of her spiritual children.

The Bermondsey annalist also notes how Catherine used casual occasions to develop ideas that were important to the vital spirit of the community. For example, the Annals records her frequent commentary on the Rule at evening recreation:

She loved to expatiate on certain words. “Our mutual respect and charity is to be ‘cordial’—now ‘cordial’ signifies something that revives, invigorates, and warms; such should be the effects of our love for each other.” Mercy was a word of predilection with her. She would point out the advantages of Mercy above Charity. “The Charity of God would not avail us, if His Mercy did not come to our assistance. Mercy is more than Charity—for it not only bestows benefits, but it receives and pardons again and again—even the ungrateful.”

The Limerick Manuscript, following in part the wording of the Bermondsey Annals, speaks of Catherine’s human understanding, and of the animating quality of her voice:

She did not possess worldly accomplishments but she had read much and her manners were most pleasing and agreeable. She had an extensive knowledge of the human heart and could readily adapt her conversation to the wants of those by whom she was surrounded. Everything in her she rendered subservient to the Divine Honour and her neighbour’s good, for she never seemed to think or care for herself. Her method of reading was so delightful that all used acknowledge it rendered quite new to them a subject which perhaps they had frequently heard before.

Not all of Catherine McAuley’s instructions were public or verbal. The eye-witness accounts of her life are threaded with instances of private accommodation to another’s frame of mind and indirect teaching through example. The Bermondsey Annals recounts an incident that Clare Moore could have learned only from the one who experienced Catherine’s apology:

One act of self abasement which occurred within the last four years of her life ought not to be passed over in silence; it was related with tears by the Sister who was the subject of it to a friend. She had spoken, as she thought, rather sharply to her, and a few hours after she went to the Sister and asked her did she remember who had been present at the time. As several had been there, the Sister answered she could hardly say, for she had not noticed which they were, but as our Reverend Mother requested her to try and call them to mind and bring them to her, they were summoned, and when all assembled our dear Reverend Mother humbly knelt down, and begged her forgiveness for the manner in which she had spoken to her that morning.

Even on her deathbed Catherine taught her sisters the necessity of complete charity. For some reason, perhaps associated with his long-standing support of the Irish Sisters of Charity and with what he took to be Catherine’s competition with them, Dean Walter Meyler, who became parish priest of Saint Andrew’s in 1833, was, as Clare Augustine Moore puts it, “not friendly.” Their relationship worsened during their prolonged chaplaincy controversy. Clare Augustine, who was present in Baggot Street at the time, recounts the details:

One of the first things he did was to forbid the 2nd Mass on Sundays, which cut off a great resource for the charity, and he tried not to have the Charity Sermon preached in the Parish Church, but the Archbishop decided it was to be so. Many other trials sprang from the same source…. He then refused [in 1837] to let the Institution have a chaplain of its own, proposing to have the duty performed by one of the clergymen attached to St. Andrew’s. Poor Foundress, who foresaw the inconvenience of such an arrangement, refused to acquiesce, and he at once put an interdict on the chapel, so that for some months we daily, and the young women on days of obligation, went out to Mass. After almost two months, he with much difficulty permitted Fr. Colgan, O.C.C.,…to say Mass and give Holy Communion on Christmas Day; but as he declared he would not renew the permission she had to yield, and plenty of inconveniences, especially as regarded confessions of the school children, we had to endure.

Catherine’s most forceful letters are about this controversy. She complained in writing to John Hamilton, Archdeacon of Dublin, and to Dean Meyler himself, from whom she received on December 19, 1837 such a painful letter that she says she burned it immediately after reading only part of it (Bolster 43-44). She suffered greatly from the Dean’s intransigence and, as she admitted in a letter to Frances Warde, she struggled to be free of all “bitterness” (129).

Yet as Catherine lay dying on November 11, 1841, she was visited by a number of priests, including Dean Meyler. Mary Vincent Whitty, who had entered Baggot Street in 1839, was at Catherine’s bedside. Though she may not have realized the full import of what she saw and heard, the older members of the community who were with her surely did. The next day Mary Vincent wrote about the scene she had witnessed, as Catherine asked Walter Meyler’s forgiveness: “She begged Dr. Meyler’s pardon yesterday—if she ever did or said anything to displease him—he said she ought not to think of that now & promised, I will take care & do all I can for your spiritual children—she looked at him so pleased & said, will you—then May God help & reward you for it.”

In her Rule, Catherine had urged her sisters to preserve the bonds of union and charity established by Jesus Christ, and to extend that Mercy to others. In the final hours of her life, when giving spiritual lectures was no longer possible for her, she continued to animate her sisters by the means which she had always considered most persuasive: the powerful, lasting animation afforded by human example.[9]

Hearing Catherine McAuley Today

Writing to Mary Cecilia Marmion on Friday, November 12, 1841, Mary Vincent Whitty speaks of the special privilege that was hers the night before: “I had the consolation for it is the pleasing though melancholy consolation to read the last prayers for her, close her eyes & that mouth from which I have received such instructions.”

In the renewal of spirit and action in which Sisters of Mercy of the Americas and their associates are now earnestly engaged, guided by the Direction Statement of the Institute, we are, I believe, called to hear and practice in a more urgent way Catherine’s instructions, perhaps especially those about comforting and animating.

If we were to think of ourselves as explicitly called to the deliberate work of comforting the afflicted:

- We might, for example, rise each morning determined to search out the most severely afflicted, hidden in the folds of each day’s encounters, and to offer them real comfort in conscious, tangible ways.

- We might see ourselves as especially called to be comforting advocates of and presences with the afflicted ones whose paths lie outside our daily map and whose by-ways we must seek out.

- We might examine our conversations, activities, use of time, and use of material resources in terms of the extent to which they, in fact, give comfort to the afflicted.

- We might consciously prefer to visit places where people are suffering, over places for our own pleasure, and would gradually shift the center of our personal gravity from situations in which we are comforted to situations crying out for the comforting we can give.

- We might publicly and systematically defend the afflicted against the powers and designs which afflict them, denouncing those afflictive structures and working to correct or remove them.

- We might explicitly ask ourselves at the end of each day: “By whose afflicted side did I stand in deliberate solidarity today, and what did I do to comfort her, him, or them?”

If we were to think of ourselves as called, precisely, to the profound work of animating human spirits:

- We might regard every encounter and action in the course of our days as directed chiefly to this explicit purpose: to help enkindle and sustain the hope, trust, and love which is the Spirit’s live-giving presence within all people.

- We might animate and inspire one another by speaking more openly about the Christian realities which personally animate and inspire us: we might talk about these realities with less reticence and privacy.

- We might find, in our relations with co-workers and those we serve, sensitive ways to speak of God and Jesus (Christ), so as not to let weeks and months go by without giving an account of the hope that is alive within us, or of our gratefulness for and confidence in God’s Mercy.

- We might be, quite plainly, cheerful and cheer-bestowing, because the “good news” which animates us and can animate others is profoundly cheering, even when other “news” is heart-rending.

- We might regard “religious education,” broadly and deeply understood, as the quintessential ministry of each of us, whatever our job descriptions or locations.

- We might defend God’s living presence in all its vital human forms, and work against non-life-giving practices and systemic death-dealing wherever they occur.

- We might be ourselves deliberately animated by the practice of Jesus, and explicitly offer his example for the animation of others.

If we were to give ourselves to some such focused personal renewal, would we not re-create the original spirit of our Institute in so vigorous a way that we would be as lively and zealous as Catherine’s “first-born” who, as she said, “renew my poor spirit greatly” (226)?

Notes

[1] While I regret certain over-simplifications and generalizations in their treatment of women religious, I applaud what Bonnie S. Anderson and Judith P. Zinsser have done for our knowledge of the history of women in Europe, in their two-volume A History of Their Own (New York: Harper and Row, 1988). A comparable work remains to be written for women in church history. Towards this end, scholarly research on the life and work of Catherine McAuley can contribute eventually to a fuller accounting of nineteenth-century Irish church history, and church history in general.

[2] Frequent reference is made in this essay to several early biographical manuscripts and letters about Catherine McAuley written by her earliest associates, as well as to entries in the Annals of certain early foundations. I here wish to thank the particular archivists, assistant archivists or other sisters for their gracious help to me and to note with respect their fidelity to caring for the documents of our heritage: Sisters Teresa Green (Bermondsey), Norah Boland (Brisbane), Nessa Cullen (Carlow), Mary Paschal Murray (Derry), Mary Magdalena Frisby (Dublin)—who has long borne a special responsibility, with great wisdom and solicitude—Mary Pierre O’Connor (Limerick), and Mary Celestine (Tullamore).

[3] References to the Rule are to Catherine McAuley’s hand-written manuscript, preserved in the archives of the Sisters of Mercy, Dublin. Chapter and article (paragraph) numbers are noted in parentheses, separated by a period.

[4] In this essay references to Catherine’s letters are generally to the edition of Mary Ignatia Neumann, RSM, The Letters of Catherine McAuley (Baltimore: Helicon, 1969), and thus only page numbers are given in parentheses. Where the reference is to the edition of Mary Angela Bolster, RSM, The Correspondence of Catherine McAuley (Cork and Ross: Sisters of Mercy, 1989), this is noted in the parentheses.

[5] In her excellent article, “Towards a Theology of Mercy,” In The MAST [Mercy Association in Scripture and Theology] Journal 2 (Spring 1992), 1-8, Mary Ann Scofield, RSM, provides a fine analysis of the conception of Mercy—doing which must have inspired and directed Catherine McAuley. In the present article, where I focus on the language of “comforting,” I wish only to offer another way of naming the mercifulness which characterized Catherine’s attitudes and behavior-by using a word she used more frequently than “merciful” or “mercy.” The words and concepts Sisters of Mercy use to express our most fundamental convictions and commitments can, by very reason of the frequency with which we use them, grow overly familiar and so lose some of their power to inspire us. This can happen with the word, “mercy,” which signifies such rich biblical and historical realities. Perhaps reflection on “comforting the afflicted” can renew our grasp of certain aspects of the mercifulness which is the founding charism of our Institute.

[6] The Oxford English Dictionary indicates that the current meanings of the word, “comfort”—as well as of the word, “animate,” to be discussed later—were also the standard meanings of these words in the early nineteenth century when Catherine McAuley used them.

[7] Sallie McFague’s Models of God (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1987) offers a persuasive interpretation of the modes of God’s presence in and toward the world “as mother [parent], lover, and friend of the last and least in all creation” (91). While McFague does not explicitly name any of her three models “Comforter,” her experimental presentation of these three metaphors of God—to represent God’s “creative, salvific and sustaining” love, activity and ethic—can immensely enrich our understanding of the scriptural presentation of the “God of all comfort” who effects and sustains “the consolation of Israel.”

[8] This eye-witness account is the earliest source of the “good cup of tea” tradition, which Mary Austin Carroll, Life of Catherine McAuley (New York: Sadlier, 1890), later records as a “comfortable cup of tea” (437). Carroll’s work was first published in 1866.

[9] Portions of this essay are taken from two chapters in the book on Catherine McAuley which I am completing for publication. The book will contain the texts of early biographical manuscripts about Catherine, as well as the text of Catherine’s original manuscript for the first Rule and Constitutions, together with extensive notes and commentary on its composition. I distributed the text of the First Part of the Rule and my end notes on it at the Governing Board Meeting of the Federation of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas, in Manchester, New Hampshire on June 24, 1989.

This article was originally printed in English in The MAST Journal Volume 3 Number 1 (1992).