The coronavirus originated in China and spread rapidly throughout the world in 2019. By March of the following year, the World Health Organization declared Covid-19 a pandemic and recommended masking, social distancing and enclosures. These restrictions heightened the rising diversity observed among political and religious leaders. This article will explore potential reasons for the various theologies articulated by the Church’s hierarchy. Prior to discussing this phenomenon, a brief review of a few past pandemics might be helpful to identify some common elements.

Historical Pandemics

The Catholic Church has frequently been involved in societal crises. This is especially true during a pandemic. A pandemic tends to elevate diverse viewpoints and sometimes promotes change within a culture. Both of these elements were visible during the pandemic of the Roman Empire in 165 CE

Roman Empire Plague

One of the earliest plagues occurred within the Roman Empire, and heightened the growing tensions between the citizens and non-citizens. The disease nearly wiped out the Egyptian and Roman communities. Babies were especially vulnerable. Thus, Church leaders decided to baptize all infants. This was a shift in the Christian practice.

Black Plague

The Black Plague originated in Asia and traveled by way of the trade routes to the West and killed over 50% of the world’s population (1347-54). Some people blamed the plague on God (Dt. 28:15), while others attributed it to the Jews. Pope Clement dispelled these myths in two Bulls released in 1348. In Quamvis Perfidiam, he condemned violence and said those who blamed the Jews were victims of lies.1

Spanish Flu

Several pandemics emerged throughout the 20th and 21st centuries but had little impact on Americans. However, the Spanish Flu was different (1918-20). It spread across Europe, Asia and the U.S. primarily by soldiers fighting in World War I. The virus attacked all age groups, but especially those between the ages of 15 and 44.

In the Fall of 1918, large groups gathered in theaters to celebrate the ending of the war on November 11, 1918. A second and third wave of the disease followed, and public officials mandated the closure of businesses, schools and churches. Some residents accepted the restrictions as necessary, while others argued the restrictions violated their rights as Americans. Christians may have been among those who protested, while Cardinal Girolamo Gastaldi published guidelines for responding to pandemics in 1684.His recommendations are still used today.2

Covid-19

The resistance to the restrictions during the Spanish Fu pandemic bears a striking resemblance to that witnessed during Covid-19. Like the victims of the Spanish Flu, contemporary Americans are suffering from both the disease and the rising factions within society. Over 1 million Americans have died from Covid-19 and another 10 per week are dying from mass shootings.

Some people have ignored government restrictions because they believe their rights supersede those of others. In addition, some Bishops continue to refuse to implement Vatican II practices. These varying positions seem to be rooted in two distinct Vatican Councils.

Diverse Theologies Within the Church

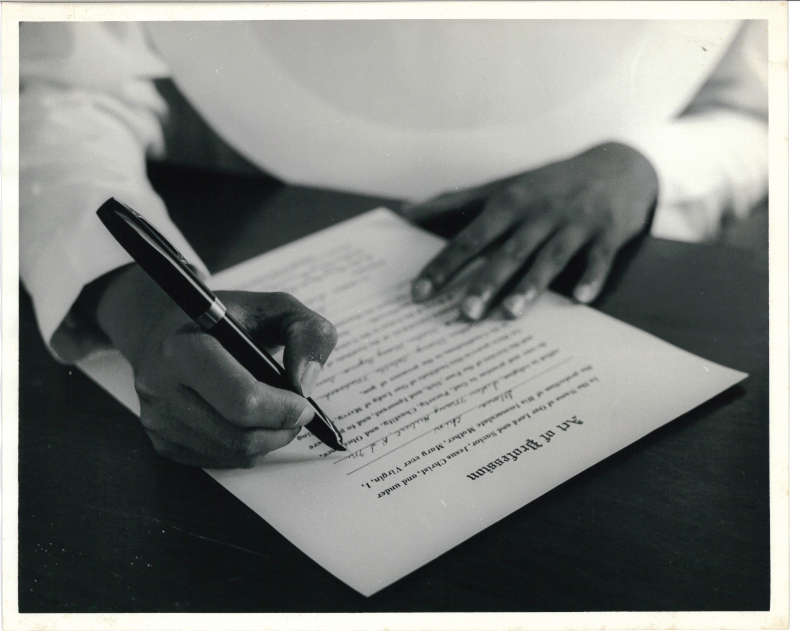

Traditionally, an ecumenical council is called by a Pope to discuss rising problems within the Church. Pope Pius IX called the First Vatican Council to strengthen the position of the papacy (1869-70). In Pastor Aeternus, the Bishops affirmed the supreme power of the Pope over the entire Church. In addition, all moral decisions made by the pope must be accepted by all Catholics.3

A century later, Pope John XXIII called the Second Vatican Council (1962-65). The Bishops attending this Council saw their roles differently. They wanted to reclaim the spirit of the early Church rather than establishing laws and regulations. Pope John desired a Church where everyone was welcomed (Gal 3:28). To achieve this goal, the Council Fathers affirmed the use of the vernacular in liturgical services and advocated collegiality between the Pope and the Bishops.4 Unfortunately, Pope John died in the midst of the assembly in June 1963. He was succeeded by Pope Paul VI who implemented the mandates of the Council (1963-78).

However, these new norms were met with some negativity. For example, Pope Benedict (2005-13) rejected the idea of ordaining women and the use of contraceptives.5 Pope Benedict resigned in 2013, and Pope Francis was elected his successor. Like Pope John, Francis desires a return to the theology of the early Church where compromise is possible (Gal 5: 1-7).6 However, the theology of Vatican II is still being challenged by a number of Bishops.

Bishops Resist the Theology of Vatican II

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the USCCB agreed to suspend liturgical services and the sacraments. These decisions raised some questions among healthcare professionals about the reception of the sacraments for dying patients. The Bishops responded by saying only a priest could administer the oils.7 Richard McBrien, a theologian, once said a church that denies the sacraments is not the Church of Christ.8 Others argue Jesus healed on the Sabbath when it was necessary (Lk 6:6-12). This issue has not been resolved.

In 2021, the Bishops met again. Archbishop José Gomez of Los Angeles argued that President Biden’s position on abortion and LGBTQ were contrary to Catholic doctrine. Following Pope Benedict’s warning to politicians in 2004, Archbishop Gomez said Biden should be denied the reception of the Eucharist. Cardinal Wilton Gregory, of Washington D.C., refused to implement this recommendation. Despite significant resistance and division among bishops themselves, Francis continues to offer a vision for a new Church.

Pope Francis Offers a New Vision for the Church

Pope Francis describes the cloudiness over society as a culture of indifference toward the common good. By employing a strategy of relentless criticism one group tends to dominate over another. In his encyclicals, Evangelii Gaudium and Fratelli Tutti, Francis proposes a way to revitalize the Church9. He believes the Church is called to be the House of the Father and the doors are always open (EG, §47). However, today’s rapidly changing culture demands new ways of expressing unchanging truths (EG, §41).

For example, discernment on the part of the Church may reveal customs that no longer reflect the Gospel values (EG, § 43). To promote this study, Pope Francis appointed both the laity and priests to serve on the governmental committee of the Church. Previously, this role had been assigned only to priests. Pope Francis’ changes within the Curia met with some opposition, but a stronger resistance came from the Synod on Family (2014-5) which raised, among others, the issue of whether divorced and re-married Catholics could receive Communion.

The Eucharist is Denied to Divorced and Remarried Catholics

The Bishops remains divided on the reception of the Eucharist for divorced and remarried Catholics. Some bishops affirm the traditional position that says a marriage between two baptized Catholics can never be dissolved (Mt 5:31-32; 19:3-12). Other bishops argue God’s revelations are continuous and adaptive. What was preached in one era may not be relevant to a situation that is different today. For example, priests and Bishops owned slaves at one time; this practice is condemned today. Despite their arguments, the bishops failed to pass an inclusive proposal on the reception of Eucharist.

Pope Francis was disappointed with the bishops’ decision. He wrote Amoris Laetitia to offer an alternative opinion.10 In this encyclical, Francis says remarried Catholics view this regulation impossible to observe. Francis claims the Eucharist is intended to nourish the weak.11 Pope Francis’ encyclical polarized the Church’s hierarchy even further. In fact, Cardinal Raymond Burke said the document shouldn’t even be considered an encyclical. However, the document stands as promulgated.

A Hope for a New Church

Pope Francis believes in a Church where all are welcome (Gal 3:28) and where walls that separate people are torn down (Eph 2:14-19). Acknowledging the tensions within the Church, Francis offers a way to build a more unified Church. In Fratelli Tutti, Francis advocates active listening, dialogue and strengthening the idea of social friendships that encourage caring for each other.12 This process was incorporated into the preparatory phase for the 2023-24 Synod.13

During the preparatory phase, several controversial issues emerged. Some of these issues included married priests, women deacons and welcoming the LBGTQIA community into the Church. All of these issues are scheduled to be discussed during the Synod.14 Hopefully, the Bishops will listen carefully to the needs of God’s people and take steps to implement necessary changes. This is Pope Francis’ hope and one I think the People of God desire!

Endnotes

1 Clement VI, Quamvis Perfidiam (26 September 1348). See https://en.wikepedia.org.

2 Cardinal Girolamo Gastaldi wrote a manual on how to respond to plagues.

3 Pius IX, Pastor Aeternus (18 July 1870). See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pastor-aeternus.

4 Lumen Gentium (18 November 1964), §§ 10-11,13,18.

5 Benedict XVI reaffirmed the ban on women priests in 1994. See Pia de Solenni, “Benedict XVI and the Role of Women in the Church.” https://wwwcatholicculture.org/culture/library/view. He also forbade the use of condoms even during the zika virus crisis.

See https://aleteia. org/2016/02/16/no-pope-benedict-would-n…

6 The German bishops are demanding changes in the Church relative to women priests. See Renardo Schlegelmilch, “Is the Threat of a Schism Between the German Bishops and the Vatican Real?” NCR (19 August), p. 7.

7 Leonne Lawrence, “US Bishops Suspend Last Rites in Response to the Coronavirus Pandemic,” News (31 March 2020). Bishop Lenard Blair, chair of USCCB, said it was

impossible for the anointing to be delegated to someone other than a priest.

8 Richard Mc Brien, Catholicism (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1981), 788.

9 Francis I, Evangelii Gaudium (24 November 2013) and Fratelli Tutti (3 October 2015). References will be shown by

the abbreviations EG and FT and the paragraph numbers.

10 Francis I, Amoris Laetitia (19 March 2016) § 350.

11 Ibid., footnote 351. Francis said: “I would also point out that the Eucharist is not a prize for the perfect, but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak.”

12 Francis I, FT, §§ 5- 8; 48-50.

13 Shawn Blanchard and Kristin Colberg, “Synodality and Its Roots in Vatican II” (National Institute for Newman Studies: September 19, 2022). Vatican II adopted the concept of synodality used by the Church in the 17th and 18th centuries. Pope Francis may have chosen it for the 2022 synod theme because it is at the heart of Vatican II.

14 The USCCB welcomed the release of the Instrumentum Laboris for the Synod on June 20, 2023.