The history of the Sisters of Mercy is a history of radiant public symbols: living persons, objects, events, and actions that by their symbolic character and presence proclaim the enduring and gracious mercy of God. Some of these symbols have remained constant in their vitality for 170 years; some have evolved ” into new symbolic forms; some have been newly retrieved from the past; and some await evolution or retrieval. Some are themselves orally mute but nonetheless have voice. All have the graced potential to give public utterance to the central mysteries of God and, in that context, to the intended reality of our lives as Sisters of Mercy. Our very name—”of Mercy”—is such a symbol.

A Figurative Utterance of God’s Promise

As a religious institute, our announced ecclesial purpose is to be the poetry and prophecy of the mysteries of God: to be a sustained metaphor of the Gospel, an abiding simile of the reign of God, an enduring symbol of the boundless love and mercy of God. Our communal purpose is thus to be a public, figurative utterance of God’s promise to console and comfort our sisters and brothers in this world.

It is perhaps a measure of our recent collective poverty of imaginative symbolizing that when we and our colleagues in the church reflect on the symbols of religious life we think first, and perhaps only, of the religious habits most of us no longer wear. For well over a century, our Mercy religious habits spoke eloquently to some people, and in some places they may still speak eloquently. But the black dress, the coif, and the veil of former days were not even then the only or the most resonant of our symbolic utterances in the public sphere. Our habits had, it is true, the precious quality of public visibility, but by themselves they were not in the past, and cannot be now, a complete symbolic utterance or an unambiguous statement of the realities of God’s presence or of the deepest meanings of our lives as Sisters of Mercy. But what symbols have replaced or will replace our religious habits?

The task before us now, on the eve of the next 170 years of our corporate life, is renewed symbol-making and symbol-offering. Our present task is to discover, recover, make, remake, create and then utter in audible, visible, tangible ways the freshly radiant symbols of the inaudible, invisible, intangible realities of our purpose and meaning as Sisters of Mercy, whether these fresh and vital symbols turn out to be “old” or “new,” and whether they are linguistic symbols (such as “of Mercy” in our name) or non-linguistic symbols (such as the character and location of the places where we live).

It is perhaps a measure of our recent collective poverty of imaginative symbolizing that when we and our colleagues in the church reflect on the symbols of religious life we think first, and perhaps only, of the religious habits most of us no longer wear.

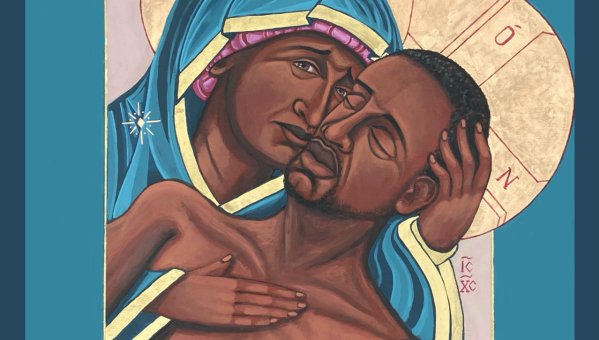

True Christian symbols are consistent, expressive, sensibly vivid incarnations of God’s meanings in this world: they are light-giving sacramentals of God’s gracious acts and commitments. Jesus of Nazareth was in his earthly life, death, and resurrection, and is now as the Christ, the absolute symbol of God, the only completely rendered symbol of God’s unconditional, merciful redemption of all creation. But we are called to follow Jesus in that symbolizing mission, however fragmentarily and partially, in total dependence on the sighs and groans of God’s Spirit.[1]

The Symbolic Expressions of Catherine McAuley and our Foremothers in Mercy

This is not a new task for us. From the very beginning Catherine McAuley and the first Sisters of Mercy were themselves symbolic utterances of God, and they created symbolic expressions of God’s merciful presence among God’s people. The resplendence of Catherine’s very life in her own time, as well as the vivid memory of her life that still radiates among us, constitutes one of the most pregnant and enduring symbols of the life and mission of the Sisters of Mercy. The oft-told story of Catherine McAuley still speaks in our world, still calls, still invites, still prophetically declares the desires of God and the intended reality of her followers. Her public life was a Christian symbol in the 1830s, and the memory of her life remains an inexhaustible symbol for those who encounter her story and are moved by its luminous generosity. Her life-story itself has now become a sacramental, and her very name now symbolizes both God’s merciful presence in the world and the aspirations of her disciples.

The resplendence of Catherine’s very life in her own time, as well as the vivid memory of her life that still radiates among us, constitutes one of the most pregnant and enduring symbols of the life and mission of the Sisters of Mercy.

The House of Mercy Catherine built on Baggot Street, her grave at Mercy International Centre, her silver ring, her portraits and statues: all these tangible realities are a silent, but public voice to those who encounter them. They speak of a human life surrendered bravely and cheerfully to the mysterious call and promise of God. The accounts of her cloak, her prie-dieu, her worn shoes, the room in which she died, the candle she held as she lay dyng, and the good cup of tea she offered for our comfort: all these perceptible objects have become symbols of the presence of God in her life and in our corporate life as her followers.

A living symbol is something that stands for or suggests something else by reason of intimate relationship or association. Some symbols, better called signs, are only accidental or merely conventional simply superficial ciphers contrived to signal some reality, but not to stand for it in any existential way. Red, yellow, and green traffic lights are such signs to be taken seriously, of course, but not experienced as conveying the intimate self of the sign maker.

True symbols are intimate expressions of the inner reality of the symbolizer, and they are, therefore, inexhaustible: there is always more to what they voice. And the “more” of truly religious symbols, however human and finite they appear to be, is always the hidden mysteries of God’s voice and presence in union with the human reality of the symbolizer. Such symbols speak without speech and reveal what is unspoken. In them we hear what is unvoiced, touch what is intangible, and see what is invisible. The Christian sacraments are such symbols of the redemptive activity of God and of the unalter able hope God’s activity on the Cross has affected.

The simple bodily presence of Sisters of Mercy in the cholera hospital in Galway in 1849, and at the bedsides of wounded soldiers in Turkey and the Crimean Peninsula during the Crimean War; the sheer physical presence of Sisters of Mercy at the gate of the School of the Americas, and in Honduras during Hurricane Mitch; the perceptible presence of Sisters of Mercy at the United Nations, and in hospitals and all sorts of places where real people suffer: are not all these bodily presences radiant symbols of larger Godly realities, beyond the meager, but symbolically luminous facts of their presence?

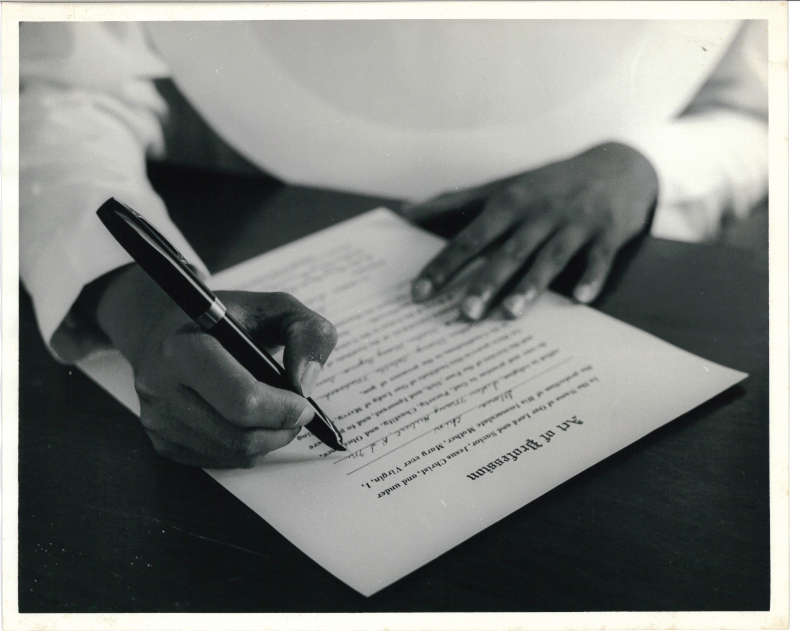

Whether it is the silver ring on our finger, the Mercy Cross we wear, the gestures of our arms and hands, the places we choose to walk or stand, the actions we take, the new Morning and Evening Prayer we pray, the community meals we share, the vows document in our hands at death: are not all these silent symbols expressive of our confidence in the reality of God’s merciful love for all people and of the final reign of that love?

Are not the physical places we have created and where we minister-the schools, hospitals, store fronts, colleges, shelters, clinics, drop-in centers, prayer centers—are not these very buildings symbolic of the mysteries of God, sacramentals of God’s persistent mercy, and visible tokens of God’s unfailing love of all humankind?

The Visibility of Mercy Life

Many commentators have spoken of the recent “invisibility” of apostolic religious life. They may be only partially correct in their assessment. They may be looking for religious habits walking down the street or sitting on the bus or kneeling in a row in church. But they may also be pointing to a certain anonymity, a certain lack of public identity, ascertain silence about ourselves—all of which are the humanly understandable consequences, though not necessary or desirable consequences, of changes over the last forty years in the church’s often ambivalent theology about us, in the church’s treatment of us, and in our own grasp of the essentials of our way of life. Our alleged “invisibility” has also been in some ways a self-protective, self healing taking-cover-a temporary respite from foll collaboration in the public mission of Jesus. After all, we say, even Jesus “took to the hills”: “after he had dismissed the crowds, he went up the mountain by himself to pray. When evening came, he was there alone” (Matthew 14:23).

In her essay on “Community Living”: Doris Gottemoeller, RSM,[2] treats the problem of invisibility as a by-product of other choices.[3] Recognizing that community living can be “an especially eloquent sign of ecclesial community, that is, of the church’s fundamental identity,” she then notes: “Of course, being a sign of something implies ascertain visibility. We have to ask: To what extent is our experience of community living visible? Who knows that sisters are present in an apartment building, a neighborhood, or a parish, and what does it say to them?”[4] The loss of visibility of place, for example, is no small matter:

At one time most local communities were associated with parishes. The parish convent and the sisters in residence there were a symbol of the compassionate face of the church, a center of hospitality and help in time of need, and a witness to the reality of our way of life. Today there is no common venue where we are present. For those who would like to know more about us, there is no place to “look” for us.[5]

Gottemoeller concludes with a central, difficult question: “How does our way of life give visible witness to simplicity, communal sharing, prayer, love for one another, zeal for the gospel?”[6]

Sociologist Patricia Wittberg, SC, raises similar questions about the necessity of visibility at the congregational level: “A congregation without a clearly articulated, visible, and collective goal will not survive as a group, although its members may continue to perform valuable services as individuals.”[7] Nor, Wittberg argues, can a handful of members carry the “visibility” for the whole group: “If religious are to be the virtuosi whose lives articulate a spiritual response to our culture’s most basic strains and discontinuities, then there will have to be a fairly large number of them. A small group is simply not visible enough to make the kind of societal impact that would need to be made.”[8]

But the fact of the matter is that, even if we tried to be so, we cannot be invisible or inaudible so long as we are in the body. The question is, rather, how will we be visible, what of us will we let be audible, what symbols of ourselves will we express in our space and time?

To what extent is our experience of community living visible? Who knows that sisters are present in an apartment building, a neighborhood, or a parish, and what does it say to them?

Symbols and the Realities of God

The symbols of our lives function as symbolic reality both for ourselves and for others. Our own selves are enfleshed in them; they are the continuation of our bodily nature. If these symbols are true of us and we are truly in them, with little or no gap between appearance and reality, they express who and what we are. They can then be for us tangible reminders of our deepest convictions and intentions. They can then also be for others a public testimony to our faith, love, and hope; to our commitment in faith, love, and hope; and to the God who is the object and guarantor of our faith, love, and hope. Our symbolic reality is then our own self-realization, put out there in the public sphere for others to perceive and query.

What our symbols can utter are the Spirit’s convictions hidden in our hearts: the reality of God’s presence and transcendence; the faithfulness and mercifulness of God; the truth of Jesus Christ and the Gospel; the indestructible power of God’s compassion and inclusivity in the resurrection of Jesus; the hope and joy and endurance of God’s promise; and our own human desire and effort to live in the strength of these realities.

We cannot compel others to understand and embrace what our symbols say. Only the Spirit of God can inspire others to explore, experience, and perhaps even comprehend the sacramentals that we are—by the grace of God. But none of this reception can occur if we are not “out there” in perceptible ways.

For example, if we could normally identify our selves as “Sisters of Mercy”; if we could usually wear our Mercy cross in public; if we could speak of God and Christ at the bedsides of the dying; if we could stand up in situations of injustice; if we could bend down in situations of great suffering; if we could evince in all circumstances the bedrock joy of God’s love for humankind; if we could somehow, in some way, symbolize the compassion and mercy of God wherever we are; if we could be, somehow, bodily symbols of what in reality we trust we are: the be loved and redeemed of God—then we could even more profoundly “serve the poor, the sick, and the ignorant” in their deepest and most lonely need.

If our communities could, by their very appearance and character, say, even without words, that we are “houses of mercy”; if our properties, and stationery, and press releases could give a perceptible clue to the nature of the Life that underlies them; if we could look and sound like something deeper than corporate businesses or professional associations or career women; if our true life could be less hidden from the public—then we could hope to do for them more manifestly what our Constitutions say we wish to do: “to follow Jesus Christ in his compassion for suffering people” (art. 2); “to proclaim the gospel to all nations” (art. 3); “to witness to Christ’s mission” (art. 5); “to witness to mercy” (art. 8); “to contemplate the Divine Presence in ourselves, in others and in the universe” (art. 9); “to discover God’s movement in us and in our world,” and to “intercede for ourselves and for others” (art. 10).

“Bearing Some Resemblance to Christ”

While she did not explicitly speak of the symbolic character of our lives as Sisters of Mercy, Catherine McAuley was implicitly aware of the nonverbal utterance of God that we are or can be. The Limerick Manuscript, in speaking of her instructions to the first Sisters of Mercy, notes:

her desire to resemble our Blessed Lord which was her daily resolution and the lesson she constantly repeated. “Be always striving,” she would say, “to make yourselves like your Heavenly Spouse; you should try to resemble Him in some one thing at least, so that any person who sees you may be re minded of His holy life on earth.”[9]

Catherine clearly thought of our lives as having the potential to be symbolic “reminders” of the great mystery of God’s goodness, as revealed in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. In the chapter of her Rule on “Union and Charity”—the chapter that represented for her the central public characteristic of communities of the Sisters of Mercy—she writes:

This mutual love, our Blessed Savior desires, may be so perfect as to resemble in some manner the Love and Union which subsists between Himself and His Heavenly Father and by this [his followers] were to prove themselves to be really His Disciples.[9]

While a symbol is never equivalent to the spiritual reality it represents, there can be enough of a like ness to it, a “resemblance” in some unmistakable way, that the reality itself is somehow pointed to and invoked. It was Catherine’s spiritual genius to recognize this potential for symbolizing utterance and to urge her sisters to deliberate care of the metaphoric quality and symbolic character of their lives. Our bodies, the capacities of our bodies, and the gestures, silences, and material extensions of our bodies speak, willy-nilly, and it was Catherine’s desire that this speaking constitute “some resemblance” to the love of God expressed in Jesus, to the faith we proclaim, and to the hope that is the world’s greatest consolation. Writing to Elizabeth Moore on Easter Monday 1841 she was eager that

God impart to us all some portion of those precious gifts and graces which our Dear Redeemer has purchased by His bitter sufferings—that we may endeavor to prove our love and gratitude, by bearing some resemblance to Him, copying some of the lessons He has given us during His mortal life, particularly those of His passion.[10]

To “bear some resemblance” to Jesus, and so to the central mystery of God, is to be a true disciple and to acknowledge the symbolizing vocation of disciples. It is a confessional utterance, a declaring of one’s faith and trust in the very way one lives and acts. The church, at least in the West, has never, to my knowledge, given the title “Confessor” to a woman, having reserved this identification for male saints who were not martyrs, but who bore “witness to the Christian faith by word and deed.”[11] Yet the Sisters of Mercy, no less than other Christians, lay and clerical, are called to be “confessors,” to give “an accounting for the hope that is in you” (1 Peter 3:15), in words and, in the absence of words, by forms, practices, actions, and gestures that “resemble” (and therefore evoke memories of) the ways of God. And so, in the symbols of our lives, we invite others to “look not at what can be seen but at what cannot be seen; for what can be seen is temporary, but what cannot be seen is eternal” (2 Corinthians 4:18).

The Care and Creation of Symbols

Symbols do not acquire long-term radiance of meaning unless they are endowed with some temporal permanence or quasi-permanence, both in themselves and in their allusiveness. One cannot “decide” that today daisies will stand for happiness, but tomorrow they will stand for dependence on God (unless of course there is a history of multivalent meanings, including these, associated with daisies). Nor can one “decide” that tomorrow violets, not daisies, will stand for happiness. Symbols are like a pebble thrown into a pond: the ripples of meaning will keep coming for a long time but will always be related to the impact of the same pebble. This is why a history of symbolic meaning should not be lightly abandoned; it takes time to build the significance of a new symbol, whereas the “old” symbol may still be “rippling” and luminous.

For example, we may have lost, through unwitting or deliberate abandonment, though perhaps not permanently, a powerful communal symbol that held meaning in most parts of the Mercy world for at least 130 years: a certain Good Friday custom instituted by Catherine McAuley. The biography of Catherine in the Bermondsey Annals tells us:

She had for many years of her life fasted on Good Friday without taking any refreshment whatever, until she became a Religious, and then she conformed to the custom which she established for the Community, of taking a little bread and gruel standing.[12]

This communal gesture of solemn restraint spoke for well over a century to Sisters of Mercy, and might still speak to them and to their friends, coworkers, and employees, about what it means to say that we are “founded on Calvary, there to serve a crucified Redeemer,”[13] and that “we are disciples of a crucified Redeemer.”[14] Reverence for the Good Friday hours of the Paschal mystery is necessary to our renewed realization of their utterly gratuitous culmination in the Resurrection-Ascension-Pentecost realities. The bodily symbol of standing as one eats has longstanding biblical associations, and Catherine’s choice of this custom reflects not only her instinct about the necessity of bodily representation of what we believe, but also her own exquisite identification with suffering:

Feeling as she did so sensibly for the sufferings of her fellow creatures, her compassion for those en dured by our Blessed Lord was extreme, so much so that it was a real pain to her, as she once told a Sister in confidence, to meditate on that subject.[15]

My goal in this essay is not to advocate any particular symbol of our lives as Sisters of Mercy, but to lift up for our communal meditation the truth that we are, as human beings and as Christians, symbol-receiving, symbol-making, and symbol-offering people whose public visibility will speak in one way or an other, whether we intend so to speak or not. Hence, our great need to care for our symbolizing that it may be truly emblematic of our deepest desires and convictions of faith, hope, and love.

In the essays which follow, on the Mercy Rituals of Reception and Profession and on the Constitutions as a symbol of Mercy life, the authors examine in detail two major symbols of our way of life. The ceremonial gestures by which we symbolize our decision to become Sisters of Mercy, and the most solemn document of our lives precisely as Sisters of Mercy, the symbol which both shapes us and is shaped by us: both of these are visible public utterances, not solely in their words, but in their character as a radiant symbolic action and object.

The Radiance of Good Example

For many years we endeavored to lead a “hidden” life, believing or being told that that was the best way to serve God and the gospel, and there is a sense in which that conviction still remains partially true. Catherine’s personal preference and teaching was no doubt born of her own very gritty public experience: “She taught them to love the hidden life, laboring on silently for God alone, for she had a great dislike to noise and show in the performance of duties.”[16] Much of our lives is purified, healed, and deepened in hiddenness, and there is true “resemblance” to Christ in that silence and privacy.

But the present state of humankind and of the church, and the sufferings of the people of this world and of Earth herself, now call us out of hiddenness into utterance and visibility, into strong clear symbols of identification, compassion, action, and advocacy or, in Catherine’s words, into example. Catherine McAuley, we are told, taught “more by her example than by words” and her lessons were always sup ported “by her own unvarying example.”[17] Exemplifying what she believed was her mode of symbolizing, for, as she explained, “the good example which we give by leading a most holy and Christian life has the greatest power over the minds of others.” Thus “we should do first what we would induce others to do,” for “the way to virtue, and to piety, is shorter by example than by precept.”[18]

When we hang the Institute Direction Statement in our classrooms; when we share the Institute Action Plan, 1999-2005 with coworkers; when we explain our Mercy Cross to patients we attend; when we tell young women about “Project 1831” and our desire to found thirty-one new Houses of Mercy; when we invite our neighbors in for Evening Prayer; and when we offer countless other gestures, actions, objects, and events to those beyond our doors, we are laying human symbols of our lives visibly before them in the hope that these symbols may speak to them of God, of Christ, and of our profound desire to live as servants of God’s mercifulness.

The enduring public symbols of Mercy life are those made visible to the wide human company of all who encounter them, in various places in the world and at various times. Sisters of Mercy going house to house during typhus epidemics in London and the United States, nursing in military hospitals in the American Civil War, following Irish emigrants on long sea voyages to Australia and New Zealand, working in refugee camps and prisons, living and ministering among oppressed people—these and thousands of other Mercy actions over the past 170 years remain in our memory as strong radiant symbols of what it has meant and still means to be a Sister of Mercy.

“Small” Symbols of God’s Presence

But in our history over these same years there have always been countless “smaller,” more private symbols of God’s mercifulness offered quietly to God’s people wherever any Sister of Mercy has held the hand of a dying person, brought joy to a neglected child, written a letter to console someone, helped a man who came to the door, visited a lonely woman, or done any of the countless gospel acts that “resemble” Jesus’ ministry. Most, if not all, of these private symbols of God’s compassionate presence have been perceptible only to the person served.

I would therefore like to conclude this meditation on the symbolic utterance of the Sisters of Mercy by looking at one little-known symbolic act of Catherine McAuley—a gift she gave to a child.

In Carlow, Catherine evidently got to know young Fanny Warde, Frances Warde’s niece, the child, possibly, of Frances’s older brother William who had died in Wakefield, England in 1839.[19] How old young Fanny was when her mother came to live in Ireland I do not know, but I suspect she was only five or six. Writing to Frances Warde on November 24, 1840, Catherine enclosed a broach and a poem for little Fanny. The poem, which Catherine titled “Little Fanny Warde,” reads as follows:

Though this is very dear to me

For reasons strong and many

I give it with fond love to Thee,

My doat’y “little Fanny.”

Six kisses too from out my heart

So sweet tho’ from a Granny,

With one of them you must not part

My doat’y—”little Fanny.”

What shall I wish, now let me see

Which I wish, most of any

That you-a nice good child shall be

My doat’y—”little Fanny.“[120]

“Doat’y” is evidently Catherine’s version of “doating” which can mean “exceedingly fond,” or of “doughty” or “douty” which means “capable, worthy, virtuous, valiant, brave.”[21] But the deepest significance of this symbol is revealed in two sentences Catherine writes near the end of her letter to Frances Warde. She says: “I promised my little Fanny a broach to fasten her collar and six kisses on the back. It was my dear Mary Teresa’s.”[22] Catherine’s beloved niece Mary Teresa Macauley had died at Baggot Street in 1833.

There are many large-scale ecclesial symbols in the history of the Sisters of Mercy, public gifts to the whole church, such as the Institute itself, but there are also innumerable small sacrificial symbols in this history, symbolic acts of love whose full meaning may be perceived by only a few. Little Fanny Warde received this broach as a symbol of a “Granny’s” love, but also, we can imagine, as a sign that a great Love was in the world and cared for her like a Granny. Only God, and to some extent Frances Warde, knew the depth of Catherine’s love for Mary Teresa, and thus the full human weight of this symbolic gift.

We have in our hands the large and small symbolic broaches of God’s love and mercy, endowed by our past joys and griefs, but even more by God’s merciful healing of all grief in the joy of Christ’s resurrection. May we, like Catherine, have the public courage and simplicity to offer these radiant symbols of God’s presence to the world.

Notes

[1] A modern theology of Christian symbolizing has been fully argued by Karl Rahner, especially in his essay, “The Theology of the Symbol” in Theological Investigations 4:221-52 (London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1966). Without attempting to summarize Rahner’s metaphysics of the symbol, its basis in his philosophical anthropology, or its extension in his theological anthropology, I have relied on his analysis in the present essay. However, Rahner is obviously not responsible for any ways in which I may have misinterpreted his intricate arguments and distinctions. His theology of the symbol fully supports, it seems to me, our contemporary theologies of the sacraments, of sacramentals, and of the significance of the ecclesial profession of religious vows.

[2] Doris Gottemoeller, RSM, “Community Living: Beginning the Conversation,” Review for Religious 58 (March-April 1999): 137-49.

[3] Gottemoeller, 142.

[4] Gottemoeller, 145-46.

[5] Gottemoeller, 148.

[6] Patricia Wittberg, SC, Pathways to Re-Creating Religious Communities (New York/Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1996), 90.

[7] Wittberg, 97.

[8] Mary Vincent Harnett, “The Limerick Manuscript,” in Mary C. Sullivan, Catherine McAuley and the Tradition of Mercy (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1995), 181.

[9] Rule 8.1, in Sullivan, Catherine McAuley, 303.

[10] Mary Ignatia Neumann, RSM, The Letters of Catherine McAuley, 1827-1841 (Baltimore: Helicon, 1969), 330.

[11] Donald Attwater, The Penguin Dictionary of Saints (Baltimore: Penguin, 1965), 23.

[12] Mary Clare Moore, “The Bermondsey Annals,” in Sullivan, Catherine McAuley, 117.

[13] Rule II. 6.2, in Sullivan, Catherine McAuley, 323.

[14] Constitutions of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas, art. 14.

[15] Moore, “The Bermondsey Annals,” in Sullivan, Catherine McAuley, 117. The sister to whom Catherine spoke in confidence may have been Mary Clare Moore herself, or her sister Mary Clare Augustine Moore.

[16] Ibid., 110.

[17] Ibid.

[18] “Spirit of the Institute,” in Neumann, The Letters of Catherine McAuley, 391.

[19] Kathleen Healy, RSM, Frances Warde: American Founder of the Sisters of Mercy (New York: Seabury Press, 1973), 84. However, Healy indicates that William Warde’s young children were named Mary and James. Sister Mary Paul Xavier Warde, Frances Warde’s grandniece, says that Fanny Warde was her own aunt, the sister of her father John Warde and Frances Warde’s niece. Fanny may have been the child of Frances’s brother Daniel, or possibly of her brother John. Healy says that Daniel “seems to have sought a career in Dublin but no record of his future is extant” (13) and that John, Frances’s “favorite brother,” died while preparing for the priesthood at Maynooth College (16). Healy also indicates that Frances’s “two nieces, Jane and Fanny Warde,” came later to Pittsburgh, and were enrolled, between 1846 and 1852, “at Mt. St. Vincent Academy and completed their studies at St. Xavier Academy” and that their brother John, Mary Paul Xavier Warde’s father, married in Pittsburgh. The identity of young Fanny Warde’s father is thus unclear.

[20] Autograph manuscript, Archives of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas, Silver Spring, Maryland.

[21] In a typescript she prepared of this poem, Mary Paul Xavier Warde, who spells the word “doat’ g,” says the word means “darling.” However, in Catherine McAuley’s handwriting the word appears to be “doat’y.” The Oxford English Dictionary is only indirectly helpful in sorting out this word and its exact meaning. Catherine often used her own spelling of words.

[22] Mary Angela Bolster, ed., The Correspondence of Catherine McAuley, 1827-1841 (Cork: Congregation of the Sisters of Mercy, Dioceses of Cork and Ross, 1989), 170.

This article was originally printed in English in The MAST Journal Volume 10 Number 3 (2000).