Preamble: At the outset, let me make two clarifications for those other than Merton reading this essay. I am using the epistolary form because it seems the form most suited to my purpose and because it is the form I would most naturally have used if Merton were still living. Secondly, by using the term “argument,” borrowed from Merton’s novel My Argument With The Gestapo, I intend this to be more of a discussion than a quarrel. i Merton gave his novel the subtitle “A Macaronic Journal,” and described it as “a kind of sardonic meditation on the world in which I then found myself: An attempt to define its predicament and my own place in it.”ii So, consider this epistolary essay subtitled, “A Macaronic Letter,” as a somewhat sardonic reflection on my relationship with Merton—an attempt to grapple with its complexity and my own place in it.

March 10, 2024

Dear Tom,

It appears I have been carrying on this argument with you for as long as I have known you, which is over 60 years now. Although you have been dead for almost as long, since I know you primarily through your writings. Dead or alive does not seem to have made much of a difference. In fact, as dead, you are more productive than most writers are while living. There has been one major book or collection either by you or about you published each year for as long as I can remember. How many living writers can say that?

You are more frustrating dead than alive, however, because I often feel as though I am carrying on this argument with myself, and perhaps I am. In raising these questions, I do not expect to find answers any more than you did. However, since you wrote that one “is known better by his [sic] questions than by his answers,”iii I trust that my questions will introduce me to you more adequately than a heap of answers would.

A while back I ran into a priest with whom I have a quasi-spiritual kinship. We happened to meet on a street corner—not the corner of Fourth and Walnut—and he asked me which spiritual writer I find myself returning to again and again. “Thomas Merton!” was my immediate and forthright answer, to which I added softly and more tenderly, “But he exasperates me.” Since then, I have thought more about that comment, along with the relationship I have had with you over the years and have begun to formulate this argument more carefully.

If you were still living, I would probably have written you several letters by now, so I don’t know why I have let a simple intrusion like death stop me. It has been said that relationships with you tend to be paradoxical anyway. Joachim Viens, for example, wrote “The paradox of those years was that I did not know Merton when I knew him, when I had the opportunity to write to him and speak with him.”iv Why should my relationship with you be any less paradoxical?

I am the first to admit that I haven’t read everything you have written, so my experience (hence my frustrations as well, I suspect) of you is somewhat eclectic. My father gave me his well-worn copy of The Seven Storey Mountain, which I read during retreat my freshman year in college. Drawn to religious life myself in those days, I found in you an Anam Cara—a soul-friend—and quickly devoured The Sign of Jonas and The Secular Journal as well.

My next encounter with you was the prayer, “My God, I have no idea where I am going,”v which over the years has often become my prayer as well. I suppose at that stage of my life I also read New Seeds of Contemplation, but that didn’t make as much of an impression on me as did your outcry, “My God, I have NO IDEA where I am going!” To my mind it was closely akin to that other outcry, “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me!” Both were epiphanies of the spiritual life for me, legitimizing my own outcries, I suppose, in the days when the Second Vatican Council was carrying me along in its tide.

Over the years I’ve read and re-read most of your journals but realize that they probably aren’t “real” journals any more than this is a “real” letter. Someday I hope I can actually see those journals. Maybe there I would find answers to some of my questions:

- Did you write them principally to be published or to help you understand yourself better?

- Did they change over time, or does a 1954 journal resemble a 1966 journal in appearance?

- Did you draw pictures in them, or cite cross-references?

Others have referred to your reading notebooks, which fascinate me as well. From your journals, letters, talks, and essays we have some idea of what you were reading, and William Shannon’s Silent Lamp: The Thomas Merton Story provides us a chronology of works published in each year,vi but did you read all of them? In my imagination these notebooks contain favorite passages, and perhaps even your ruminations about them. Did you dialogue with books in the margins the way I do?

In the interest of organizing my argument, there are three key topics I would like to discuss with you: self-reflection; the ministry of writing; and your charism.

Self-Reflection

One of my principal frustrations with you is that I don’t see very much self-reflection, or what I call “personal mystagogy,” in your writings. While you spend a good bit of time with the mysteries of faith, you seem almost frightened of the mystery that is your life. For example, on January 30, 1965, you wrote: “Shall I look at the past as if it were something to analyze and think about? Rather, I thank God for the present, not for His and in Him. As for the past, I am inarticulate about it now.”vii While it is true that I sometimes look to the past as if it were something to analyze or think about, more often I find it something to marvel at—how I survived, for sure, but also how little I have changed over the years.

One Pentecost morning I found myself recalling other celebrations of the feast and thought back to my First Communion Day (June 6, 1952). A picture taken of me that day was near, so I looked thoughtfully at the little girl that I was and surprised to see the woman that I am smiling up at me. My journal notes, “I haven’t changed much … if at all. I’m still filled with the same joy and anxiety,” concluding that we stay pretty much the same through life. Apparently, you had similar flashes, for William Shannon gives us the following citation from “New Journal,” dated February 16, 1953: “I recognize in myself the child who walked all over Sussex. I did not know that I was looking for this shanty—or that I would one day find it.”viii

In your reading journal for July 20, 1956, Michael Mott tells us that you had been reading passages in Julien Green’s journals in which Green says that between the lines of what one writes in one’s journal there is a prophecy of the future.ix Where did you go with that? Did you think back on your old journals, recalling examples where this proved true, or did you just dismiss the possibility?

In The Way of Chuang Tzu, which we are told you regarded as your best book,x you include “Flight from the Shadow”:

There was a man who was so disturbed by the sight of his own shadow and so displeased with his own footsteps that he determined to get rid of both. The method he hit upon was to run away from them.

So, he got up and ran. But every time he put his foot down there was another step, while his shadow kept up with him without the slightest difficulty.

He attributed his failure to the fact that he was not running fast enough. So, he ran faster and faster, without stopping, until he finally dropped dead.

He failed to realize that if he merely stepped into the shade, his shadow would vanish, and if he sat down and stayed still, there would be no more footsteps.xi

I imagine that you laughed deeply at that, and that you saw yourself on the run. Did something like this realization in fact prompt you to write:

What I find most in my whole life is illusion, wanting to be something of which I have formed a concept. I hope that I will get free of all that now, because that is going to be the struggle and yet I have to be something that I ought to be. I have to meet a certain demand for order and inner light and tranquility, God’s demand, that is, that I remove obstacles to His giving me all these.xii

You wrote that on January 30, 1965, which was the eve of your 50th birthday. The journal notes no correlation, but I can’t imagine that your observations were mere coincidence. And did you think of it again when you were looking at the reclining Buddha in Polonnaruwa, Ceylon? On December 4, 1968, you wrote:

Looking at these figures I was suddenly, almost forcibly, jerked clean out of the habitual, half-tied vision of things, and an inner clearness, clarity, as if exploding from the rocks themselves, became evident and obvious . . .. Surely, with Mahabalipuram and Polonnaruwa my Asian pilgrimage has become clear and purified itself. I mean, I know and have seen what I was obscurely looking for. I don’t know what else remains, but I have now seen and have pierced through the surface and have got beyond the shadow and the disguise.xiii

Had you lived longer, I wonder if you would have returned to the subject of “The New Consciousness,”(maybe a “newer consciousness”) on the human need for “liberation from inordinate consciousness, monumental self-awareness, obsession with self-affirmation, in order to enjoy the freedom from concern that goes with being simply one who is and accepting things as they are in order to work with them as one can.”xiv

Ministry of Writing

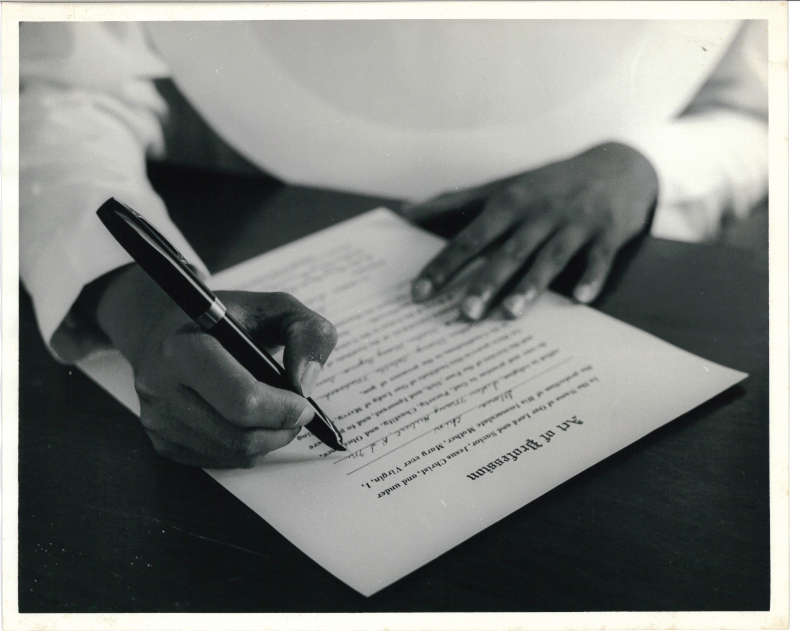

The second point in my “argument” with you relates to writing, with which both you and I have struggled. Your struggle, like mine, seems to have had two phases: writing as duty and writing as responsibility—my terms, not yours. By “writing as duty,” I am, referring to your early works, those you were “required” to write, and which you label “poor,” “very poor,” or “awful.”xv Ron Seitz recalls you saying, “If writing is involved with ‘duty’ or ‘productivity,’ in a word, justification, then you’re finished as an artist.”xvi I know that kind of writing too. I remember the intense pressure to publish in the years before I was awarded tenure, but since then I have come to know another kind of writing, what I call “writing as responsibility.” By this I mean writing as vocation, as art, as an expression of who I am as well as what I think—writing as liberation.

Seitz’s recollection continues, “Dare let loose the body and speak whatever spirit says first this head of yours … Loose the knows and allow your heart to sing whatever it asks.”xvii Finally, in Seitz’s “memory vision” I have found answers to questions I have been asking for many years. While preparing this “argument,” I returned to my Merton library and not only discovered you anew, but myself as well.

In his Preface to The Hidden Ground of Love, William Shannon observed that the success of The Seven Storey Mountain may well have released you from your attraction to fiction and turned you toward a form of writing more congenial to your talent.xviii Eight years after first reading that, I was surprised to find that I had written in the margin, “I wonder if I would have a similar result in writing the fiction I long to write.” I hadn’t realized that my “longing” had been there so long, but now I see that I have lived on into an answer.

When I posed that query in The Hidden Ground of Love, I was still two years short of being tenured and feeling the proverbial pressure to publish or perish. Writing was arduous for me, although researching was a delight. I could spend hours lost in footnotes hot on the trail of some minute detail, but agonizing over sentences, editing and re-editing each section of the essays that would convey the results of that scholarship. While becoming tenured in an academic institution can often sound the death knell for research and writing, for me it was the release I needed to birth the artist-within. It was a breech-birth, I think, and an excruciatingly long labor. That longing to write fiction, which I didn’t even remember having eight years before, became a burning desire I could no longer deny, and I finally began to discover ways to honor and nurture my vocation as a writer.

For all those years I have looked to you for advice on how one nurtures the writing-vocation, only to be dragged around in your circles, where you repeatedly “vow” to give up writing completely. I have never considered making such a “vow,” but each time I come upon such a reference in your books I wonder if your problem lay with writing itself or might more accurately have been a struggle with balance.

Like yourself, “I am only fully normal and human when I have plenty of solitude . . . living according to a different and more real tempo. I live with the tempo of the sun and of the day, in complete harmony with what is all around me.”xix In the pandemic times, many of us learned to live according to a “different and more real tempo.” But what frustrates me is that you connect that “solitude” almost exclusively with the hermitage, while I see “solitude” as more internal than external.

In the same text, a few days later you wrote, “Meanwhile, I feel a great deal of inner tension, a deep, frantic, knotted anguish of helplessness in the center of me somewhere . . ..”xx I know the inner tension, the frantic, knotted anguish in the center of my being, but unless I allow that to be untied within, no hermitage outside will give me peace. Didn’t it strike you as more than incongruous that your great theophany occurred on the corner of Fourth and Walnut, and not in your hermitage?xxi

Finally, “at peace” in your hermitage you wrote, “One has to be in the same place every day, watch the dawn from the same window or porch, hear the selfsame birds each morning to realize how inexhaustibly rich and diverse is this ‘sameness.’ The blessing of stability is not fully evident until you experience it in a hermitage.”xxii I sat in my rocking chair, where I sit each morning to pray, reading that statement and feeling my blood pressure rise. Far from what anyone would call a “hermitage,” I watch the dawn from the same window and hear the selfsame birds (squawking geese!) each morning. For forty years most mornings, I saw dawn approach each morning by looking through the rear-view mirror of my car. Being in the same place at the same time each day isn’t a phenomenon; being mindful and noticing is. Stability requires one to become stilled internally. Only then is it a blessing. Discovering a blessing in the imposed stability required during those pandemic times continued to be a challenge.

Enduring Charism

The third and final point of this argument relates to your charism. At the outset, I remarked on the fact that at least one book by or about you is published each year. You generate an incredible amount of interest. What is it about you that more than fifty years after your death speaks so strongly to so many people around the world? I think you provided part of the answer in your Preface to the Japanese edition of The Seven Storey Mountain, dated August 1963: “I seek to speak to you, in some way, as your own self. . .. if you listen, things will be said that are perhaps not written in this book. And this will be due not to me, but to One who lives and speaks in both!”xxiii Seitz recalled a powerful conversation he had with you, which he called your “Monks Pond Sermon,” and observed that you “set something free” in him.xxiv For me that observation was a key to understanding your enduring charism: you set something free in people.

In my experience, however, there is one group of people who have generally not been interested in your work—those in my circle of monastic and religious friends, mostly male. I used to ignore their trivialization of you, but over the years I began to probe it a bit more. In the course of those conversations, I have learned that they generally dismiss you without having read you at all, or at least not beyond New Seeds of Contemplation. One monastery was reading The Seven Storey Mountain in the refectory because none of the monks had ever read it. At first, I thought that, like Jesus to the Nazareth residents, you were just too much for them, that your honesty about the struggle of living the spiritual life was in danger of breaking through their walls of denial. While in some cases that might be true, my latest conclusion is that what monastics are discomforted by is the “Cult of Merton,” what they perceive to be a romantic and frivolous attachment to the monastic mystique.

Viens has observed that “in many ways, the early writings of Merton reinforce the stereotype of the triumphalist, chauvinistic convert” and that you are “equally chauvinistic in speaking of monasticism.” Your “naïve idealization of the monastery as the Promised Land” explained why he stopped reading your works shortly after entering the monastery in 1950.xxv The same seems to hold true for many monastics.

I have discovered that I understand you and your charism better when I view things from your perspective and not theirs. When I visited your Abbey thirty years ago, stood by your grave, and then sat on the porch of your hermitage, I knew to my core that I was standing on holy ground. I wondered about that cedar cross. It wasn’t until I saw a picture of it in Seitz’s book, however, that my perspective changed. Instead of an awkwardly tall and skinny cross which dwarfed me, Seitz helped me to see it through your eyes, drawn across the sky. “Now I understand!” my notes read.

I can imagine no other joy on earth than to have such a place to be at peace in. To live in silence, to think and write, to listen to the wind and to all the voices of the world, to struggle with a new anguish, which is, nevertheless, blessed and secure, to live in the shadow of a big cedar cross, to prepare for my death and my exodus to the heavenly country, to love my brothers and all people, to pray for the whole world and offer peace and good sense among men. So, it is my place in the scheme of things and that is sufficient. Amen.xxvi

As Seitz correctly observed, I believe, you “hit home with raised finger the pulse of what we were all seeking…”xxvii And your “circular letter” written to friends in September 1968 is surely the best advice any of us is ever likely to be given: “Our real journey in life is interior: it is a matter of growth, deepening, and of an ever greater surrender to the creative action of love and grace in our hearts. Never was it more necessary for us to respond to that action. I pray that we may all do so.”xxviii

Conclusion

I began this letter quoting from your Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, and it is to that text I now return. “To make known one’s questions,” you wrote, “is to come out in the open oneself.”xxix These are different times than yours. Fides quarens intellectum goes by different names today and wears different clothes—all of which I think would intrigue you, enrage you, and probably delight you all at the same time. People are analyzing your dreams, determining your Myers-Briggs or Enneagram types in absentia. We are probably a more self-conscious lot than you could imagine, and racism, militarism and consumerism infect us still. However, there is a certain timelessness to your spirituality, so deeply rooted in the Scriptures and in Christ-love, that might always enable us simply to be at home in God’s presence and in the human family embraced by God’s love.

Catherine McAuley, founder of the Sisters of Mercy, urged the sisters to dance every evening. Well, Tom, I love to dance. I don’t know what kind of a dancer you were when you walked this earth, but you have been an excellent dancing partner from beyond the grave—leading me gently but firmly, spinning me around, making me dizzy, and even stepping on my toes every now and again. But all that is part of the joy of the dance!

I cannot dance, O God, unless you lead me.

If you will that I leap joyfully

You must yourself first dance and sing!

Then will I leap for love

From love to knowledge,

From knowledge to fruition,

From fruition to beyond a human sense . . .

There will I remain and circle Evermore.xxx

Endnotes

[1] Thomas Merton, My Argument with the Gestapo: A Macaronic Journal (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1969).

[2] Merton, Argument, 6.

[3] Thomas Merton, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1966) 5. Today I trust your language would have been more inclusive and/or your editor more vigilant. I hope you won’t mind my taking editorial license from here on in when necessary.

[4] Joachim Viens, “Thomas Merton’s Final Journey: Outline for a Contemporary Adult Spirituality,” in Toward an Integrated Humanity: Thomas Merton’s Journey, ed. M. Basil Pennington, OCSO (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1988), 226.

[5] Thomas Merton, Thoughts in Solitude (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1958), 83.

[6] William H. Shannon, Silent Lamp: The Thomas Merton Story (New York: Crossroad, 1992).

[7] Thomas Merton, Vow of Conversation: Journals 1964-1965 (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1988). 140.

[8] Shannon, Silent Lamp, 154.

[9] Michael Mott, The Seven Mountains of Thomas Merton (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1984), 292.

[10] See Ron Seitz, A Song for Nobody: A Memory Vision of Thomas Merton (Liguori, MO: Triumph Books, 1993), 169-170. Seitz recalls that Merton thought The Way of Chuang Tzu was his best book but didn’t want to say so because of the “eastern thing.”

[11] Thomas Merton, The Way of Chuang Tzu (New York: New Directions, 1965), 155.

[12] Merton, Vow, 140.

[13] Thomas Merton, The Asian Journal (New York: New Directions, 1975), 233-236.

[14] Thomas Merton, Zen and the Birds of Appetite (New York: New Directions, 1968), 31.

[15] Thomas Merton, “Honorable Reader”: Reflections on My Work, ed. Robert E. Daggy (New York: Crossroad, [1981] 1991), 149-151.

[16] Seitz, 69.

[17] Seitz, 69.

[18] Thomas Merton, The Hidden Ground of Love: The Letters of Thomas Merton on Religious Experience and Social Concerns, ed. William H. Shannon (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1985), vi.

[19] Merton, Vow, 80.

[20] Merton, Vow, 84.

[21] Merton, Conjectures, 158.

[22] Merton, Vow, 185.

[23] Merton, Honorable Reader, 67.

[24] Seitz, 79-80.

[25] Viens, 227.

[26] Merton, Vow, 152.

[27] Seitz, 88.

[28] Merton, Asian Journal, 296.

[29] Merton, Conjectures, 5

[30] Mechtild von Magdeburg, The Flowing Light of the Godhead, 1.44, trans. Lucy Menzies (London: Longmans, Green and Company, 1953), 21. Adaptation by Julia Upton.